Antarctic iceberg: Giant 'white wanderer' poised to break free

- Published

The putative iceberg has been modelled using observations from the Cryosat spacecraft

Everybody is fascinated by icebergs. The idea that you can have blocks of frozen water the size of cities, and bigger, sparks our sense of wonder.

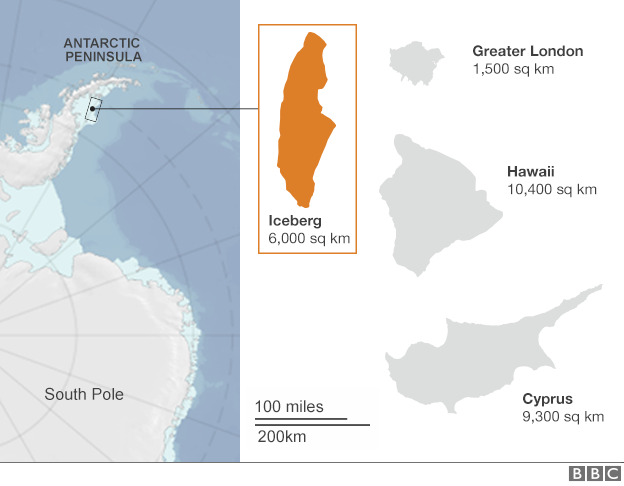

British astronaut Tim Peake photographed one from orbit that would just about fit inside Central London's ring road. But at 26km by 13km (16 miles by 8 miles), it was a tiddler compared with the berg that is about to break away from the eastern side of the Antarctic Peninsula.

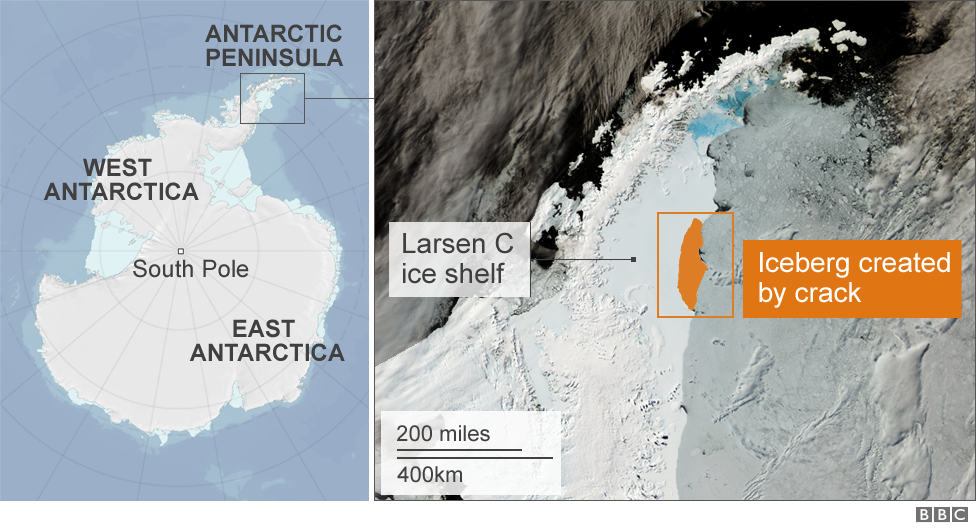

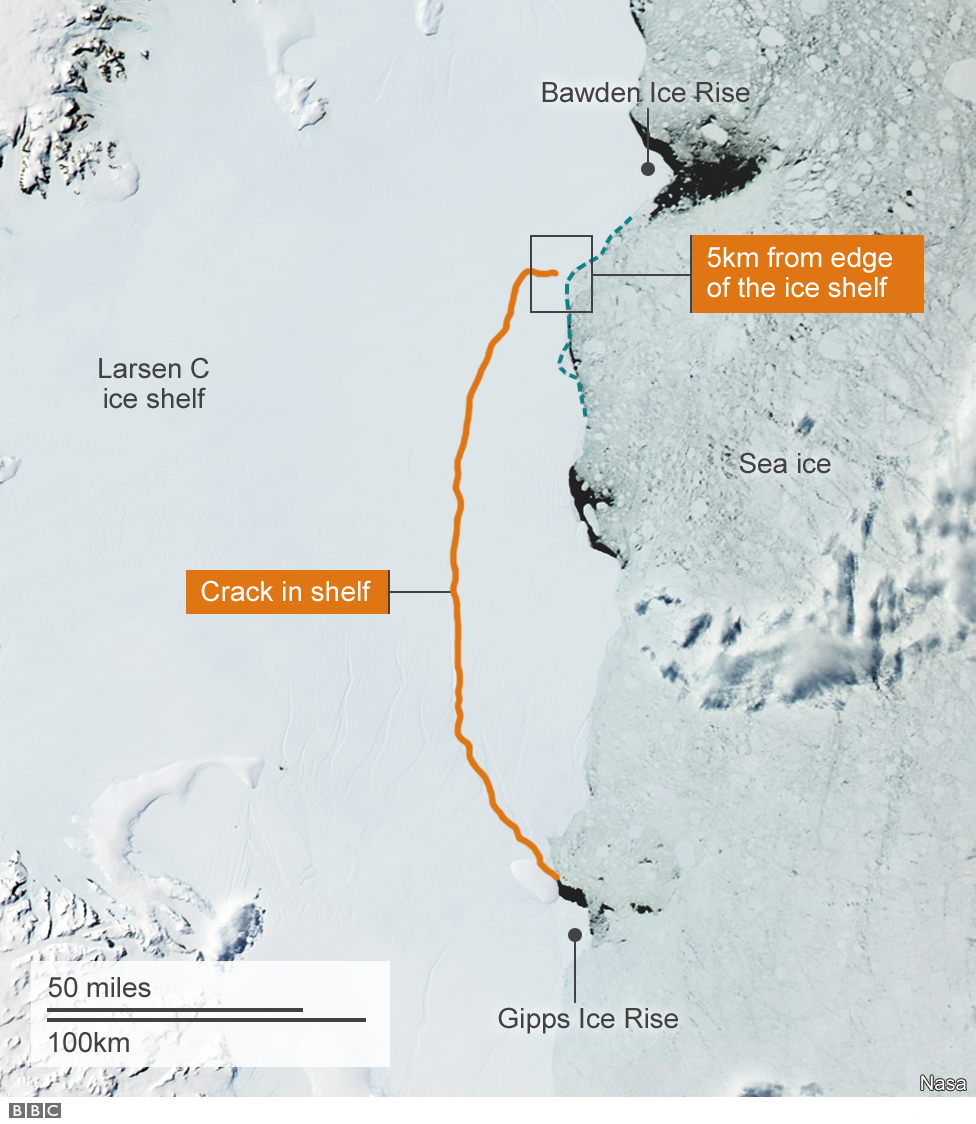

A rift has grown across the edge of the Larsen C Ice Shelf. A thin, 5km-long section of the floating shelf is now all that prevents a 6,000-sq-km berg from drifting away into the Weddell Sea.

Think about the size for a moment. That's more than a quarter the area of Wales.

Keen to gather some more statistics, scientists have used the Cryosat spacecraft to run the rule over the putative iceberg.

As we all know, blocks of ice sit mostly under the water, and the European Space Agency (Esa) satellite has a special radar altimeter that is able to figure out by how much.

From orbit, Cryosat senses the height of the ice sticking above the surface - the so-called freeboard. It's then a relatively simple calculation to work out the draft - the hidden part below water.

How big is the iceberg?

"Cryosat has these two radar antennas that allow us to get an extensive swath across the berg and enable us to build an elevation model," Dr Noel Gourmelen from the University of Edinburgh told BBC News.

From this, the average thickness of the would-be berg is calculated to be about 190m, but there are places where the draft is around 210m. It means the ice above the water surface stands roughly 30m high.

Dr Gourmelen says there is an estimated 1,155 cubic km of ice in the block.

This is all very useful information because it tells scientists a lot about where and how fast the Larsen object might move once it becomes free. And those are critical details if the berg were to reach shipping lanes to become a navigation hazard.

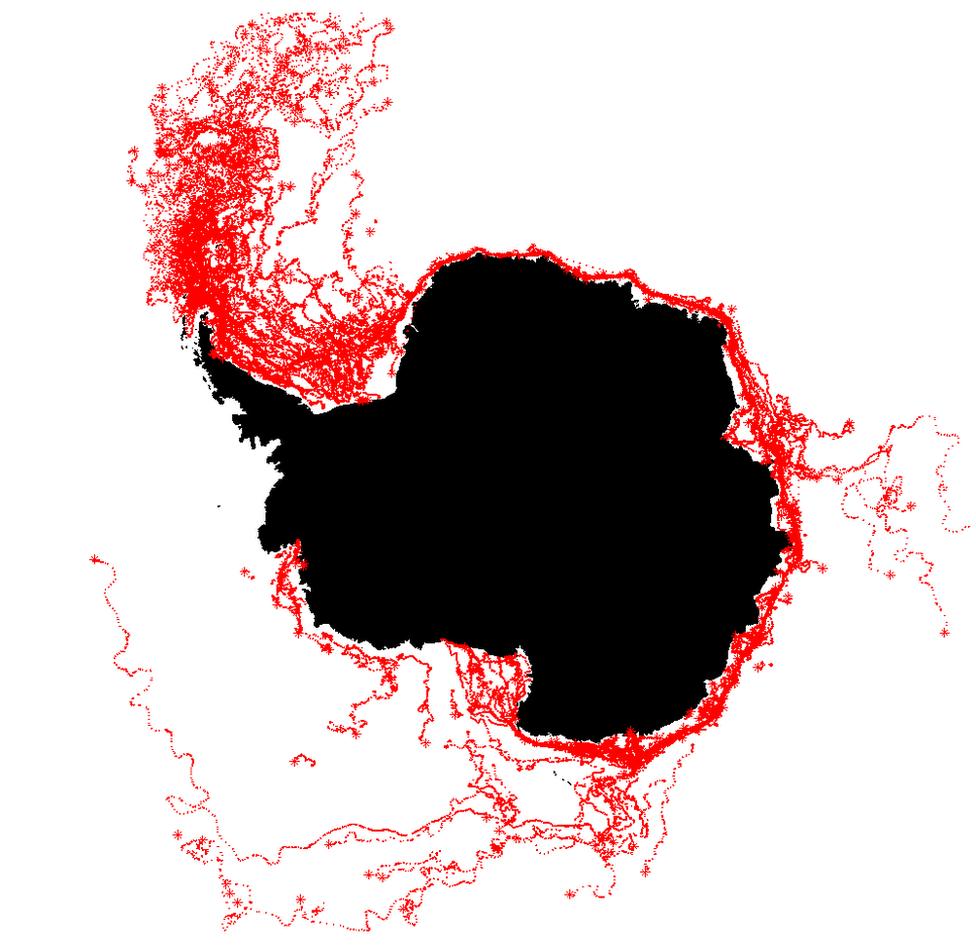

The drift paths (red lines) of countless bergs have been tracked around the Antarctic continent (black). This collective history strongly suggests the Larsen block will head for the South Atlantic

Bergs get pushed by winds and currents, of course, but a couple of other factors also come in to play simply because of the Larsen object's sheer bulk. Remarkably, one is a gravitational effect.

Winds drive sea-level higher near Antarctica's coasts compared with the centre of the ocean - by something like half a metre.

The Larsen berg will actually slide down this slope under its own weight, but it will not move in a straight line. Instead, it will veer left as a result of the Coriolis force that stems from the Earth's rotation.

This movement could be interrupted, though, if the berg's keel then gets snagged on the ocean bottom.

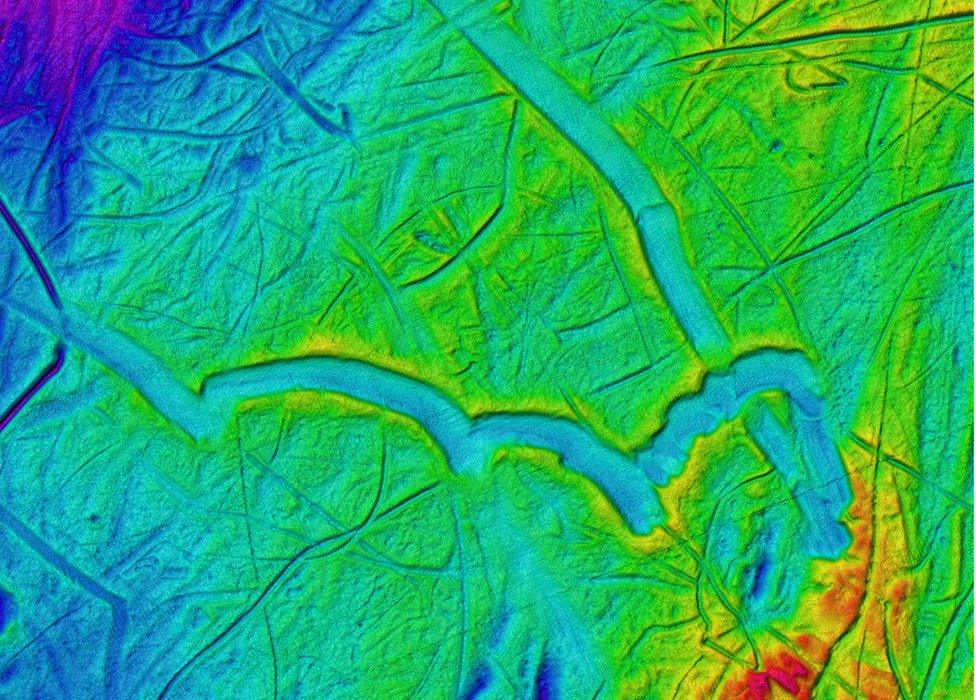

Ploughmarks: The keels of icebergs will cut deep channels in sea-floor sediments

The waters close to Antarctica are shallow and there's a good chance the berg will dig in, gouging a huge trough in the seafloor as it then turns round.

It's called "kedging" - a term used by sailors, coined from the use of the kedge anchor to manipulate the course of a vessel, explains Dr Mark Drinkwater, one of Esa's senior Earth observation scientists.

“The icebergs often shoal and pivot or spin around their grounding point, resulting in stop and go motion or a change in direction. So, the iceberg from Larsen C could take some time before it escapes the shallow [waters] of the western Weddell Sea."

Dr Anna Hogg from Leeds University added: "That said, it's not impossible it could simply become stuck on some high-rise topography on the ocean floor. We've seen that before where an iceberg becomes a semi-permanent ice island in the Weddell Sea."

The expectation, however, is that the berg will bump and grind its way northward in near-coast currents, along the Peninsula.

Past history suggests it will eventually be exported on one of four major iceberg "highways" that lead beyond Antarctica. In this instance, the route is one that sends the berg into the circumpolar current and on to an eastward arc towards the South Atlantic.

The penguins and seals on the British Overseas Territory of South Georgia may well get to see it, or its fragments, as it passes by in a few years' time. And I mean years.

Prof Helen Fricker, from California's Scripps Institution of Oceanography, says she was tracking two large objects in 1993, a full seven years after their 95km-by-95km parent berg calved from the Larsen C Ice Shelf.

Tim Peake's iceberg, known as A-56, was roughly 26km by 13km (16 miles by 8 miles)

What's nice about Tim's berg is that he managed to capture it on a normal SLR optical camera. That's unusual because Antarctica is very often covered in cloud, and it doesn't matter how big a lens you have - the ocean surface will be obscured.

It's why radar satellites are so important. The wavelengths they work at pierce cloud and winter darkness.

Indeed, the only reason we know this new Larsen berg is about to calve is because Europe's Sentinel-1 radar satellites take a detailed look at the shelf's behaviour every six days.

"What the current Larsen situation has highlighted is that we're now able to monitor the situation with a frequency we've never had before," says Dr Hogg.

"We can get pictures from the two Sentinel-1 satellites in about half an hour of them being acquired. The satellites we have now are revolutionising our study of the polar regions," she told BBC News.

How are Antarctic icebergs named?

Iceberg names follow a convention that uses a letter followed by a number

Icebergs are blocks of ice that cover at least 500 sq m

Any smaller and they are called "growlers" or "bergy bits"

The US National Ice Center runs the naming system for bergs

It divides Antarctica into quadrants - A, B, C and D

Larsen icebergs get an "A" designation when they calve

They also get the next number in the sequence of sightings

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external