Waste products, not crops, key to boosting UK biofuels

- Published

- comments

The report recommends a cap on crop based biofuels

The UK should focus on using waste products like chip fat if it wants to double production of biofuels according a new study.

The report from the Royal Academy of Engineering, external says that making fuel from crops like wheat should be restricted.

Incentives should be given to farmers to increase production of fuel crops like Miscanthus on marginal land.

Even with electric vehicles, biofuels will still be needed for aviation and heavy goods say the authors.

While the European Union has mandated that 10% of transport fuels should come from sustainable sources by 2020, these biofuels have been a slow burner in the UK.

Suppliers are already blending up to 4.75% of diesel and petrol with greener fuel, but doubling this amount will take up to 10 years say the authors of this new report, that was commissioned by the government.

To get to this point, the authors argue that several important changes will need to take place.

While in countries like the US and Brazil biofuels are mainly made from maize or sugar cane, the main sources in the UK are wheat and used cooking oil.

To boost production there will need to be restrictions on crops grown for fuel, say the authors.

Last year according to the Department for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra), almost half the land in the UK used for biofuels was used to grow wheat.

When the authors of this study reviewed the global scientific literature, they found that if all the extra emissions involved in changing land use to grow wheat were added in, fuel based on this grain was worse for the environment than regular petrol or diesel.

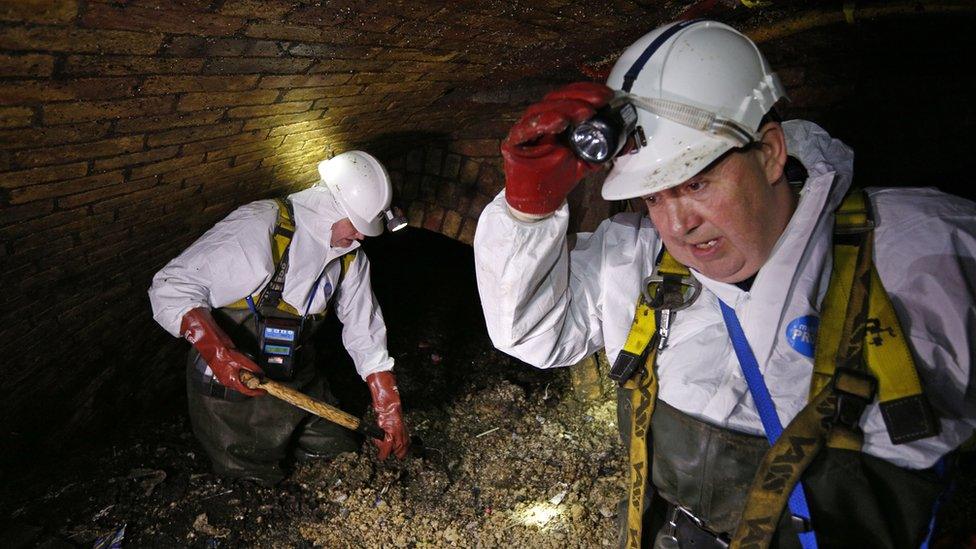

Even the fat and waste that block sewers could be used to generate biofuel say the authors

"Generally, we know if land use change is involved, do not use wheat to make biofuels, it is higher than petrol in terms of carbon footprint," said Prof Adisa Azapagic from the University of Manchester who chaired the panel that produced the report.

"What we need to understand about agriculture, is that it is different from farm to farm. This is what we have found across the world, how people farm wheat in different ways and the emissions would be different depending on soil, previous carbon stocks and so on, it really is a very complex science."

The study recommends that the government set a cap for all crop-based biofuels to reduce the risk of indirect land use change.

"We would be concerned if we went up to 10% and allowed all of that 10% to come from food based crops, then we would say no, that's not what we're recommending," said Prof Nilay Shah from Imperial College London.

Instead, the report suggests that renewed emphasis be placed on developing waste. In the UK we produce 16 million tonnes every year, enough to double our current biofuel supplies. A third of that waste is called green waste, a quarter of it is agricultural straw.

The authors believe there is great scope for expansion in the use of unavoidable waste, such as used cooking oil, forest and sawmill residues, the dregs from whisky manufacture, even so-called "fatbergs" from sewers could play a role.

However the study warns that care must be taken to avoid giving people perverse incentives to create waste just to cash in on biofuels.

Aviation and shipping are likely to need to use liquid biofuels for many years to come

"There have been some examples where people have used virgin cooking oil as a source of biofuel because it was cheaper than used cooking oil so we need to make sure we avoid these market distortions that unfortunately do happen," said Prof Azapagic.

The government should also aim to remove any incentives for the use of materials in biofuels that involve deforestation or the drainage of peat land. Incentives should be put in place to encourage farmers to grow crops like Miscanthus and short rotation coppice wood on marginal land.

If we want to double the amount of biofuel we are using over the next decade, say the authors, the government will have to stump up some cash.

"If you've got a ready supply of used cooking oil it is not very challenging or expensive, if your alternative is to go clear some land and plant Miscanthus and all the processing that goes with that, then the prices are going to be different," said Prof Roger Kemp, a professorial fellow from Lancaster University.

"We wouldn't be getting up to anything like 10% if it was purely a market based thing."

Follow Matt on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external