Drifting Antarctic iceberg A-68 opens up clear water

- Published

The giant iceberg known as A-68 that was produced in the Antarctic last week continues to drift seaward.

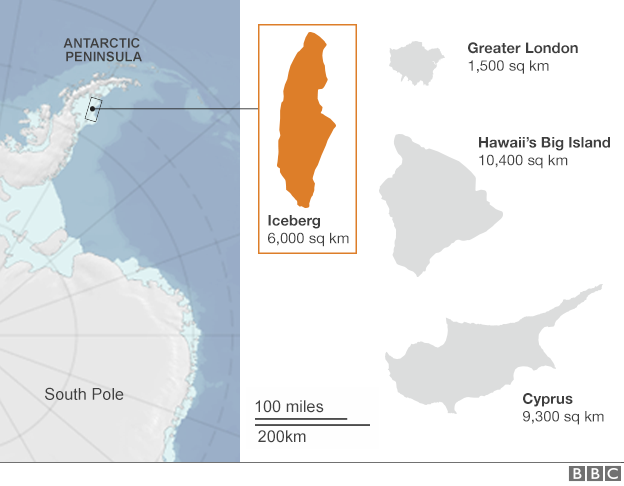

All the latest satellite images indicate the gap between the 6,000-sq-km block and the floating Larsen C Ice Shelf from which it calved is widening.

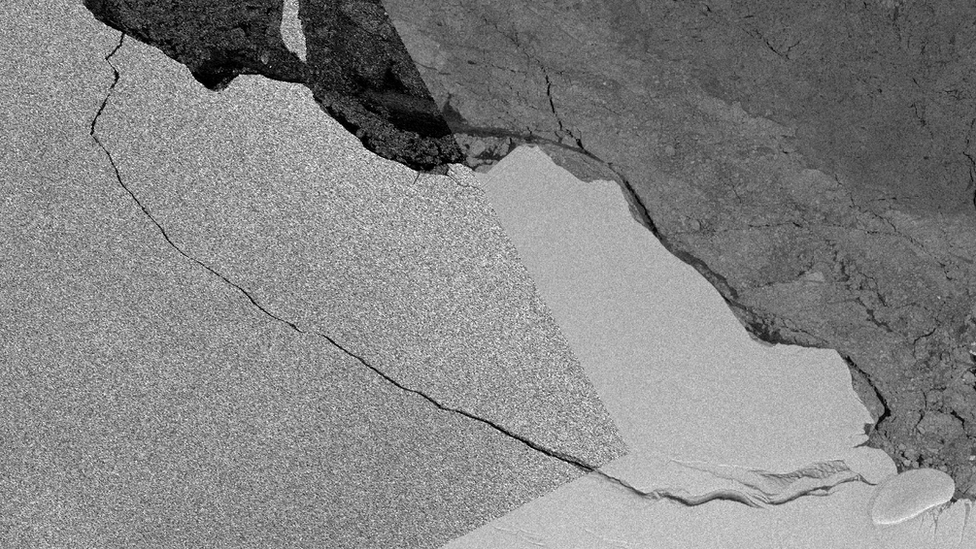

The particular image on this page was acquired by the Deimos-1 satellite.

It is not easy getting pictures of the Antarctic at this time of year because of the long winter nights and because of cloud cover.

Those spacecraft that have so far spied the berg have been relying on radar or on infrared sensors to pierce these difficulties.

The monster berg - which is a quarter the size of Wales, and one of the biggest ever recorded - is so far behaving as expected.

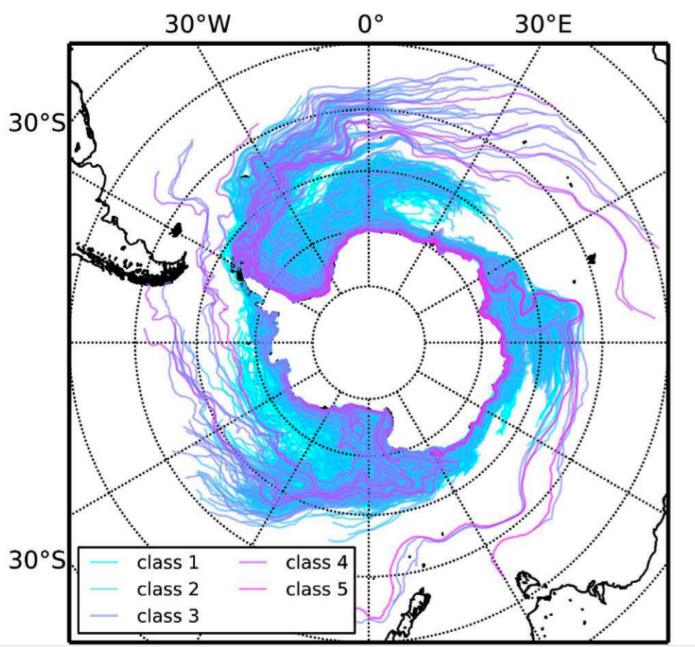

Theory suggests it should move, in the first instance, down the slope in the ocean surface that has been created by winds in the Weddell Sea pushing water up against the coast. But the leftward deflecting effect of the Coriolis force, produced by the Earth's rotation, should keep the berg relatively close to the continent's edge.

Interestingly in the Deimos image, acquired on Friday, it appears as though a large segment of "fast ice" that was attached to the berg has broken free. This fast ice is considerably thinner than the main block - a few metres thick versus the 200-plus-metres of the berg itself.

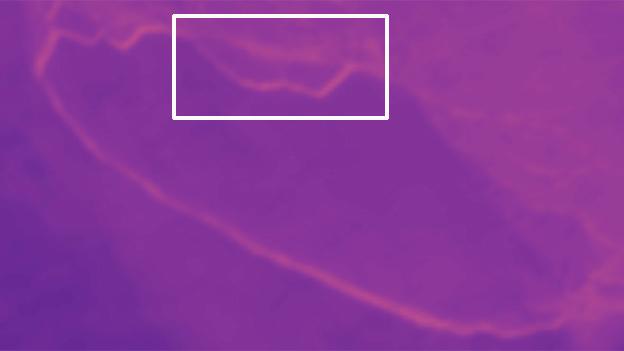

In this Sunday thermal image from Nasa's Aqua satellite, the strong white lines are the signal of water which is warm relative to the surrounding ice and air. It also suggests a large section of fast ice has detached from the berg

Thomas Rackow and colleagues from the Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research, are following the block with keen interest.

They recently published research, external in which they modelled the drift of icebergs through Antarctic waters - taking into account the different influences that act on small and large objects. There are essentially four "highways" that bergs travel, depending on their point of origin.

A-68 should follow the highway up the eastern coast of the Antarctic Peninsula, leading from the Weddell Sea towards the Atlantic.

"It will most likely follow a northeasterly course, heading roughly for South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands," Dr Rackow told BBC News. "It will be very interesting to see whether the iceberg will move as expected, as a kind of 'reality-check' for the current models and our physical understanding."

Simulated highways: Small to medium bergs (Classes 1-3) generally have a lifetime of a couple of years; the big bergs (Classes 4-5) are mostly all gone after 10 years

Polar research agencies are already discussing the scientific opportunities afforded by the breakaway.

Scientists will want to understand what effect the calving might have on the remaining parts of the ice shelf. Ten percent of Larsen C's area was removed by the departing berg, and this loss could change the way stress is configured and managed across the shelf.

There are numerous cracks just north of a pinning point known as the Gipps Ice Rise. These fissures have long remained static, held in place by a band of soft, malleable ice.

Researchers will want to check the departure of A-68 will not alter the status of these cracks.

There are also some fascinating investigations to be done on the seafloor that will soon be uncovered when the berg moves completely clear of the shelf. Previous big calvings have led to the discovery of new species.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published12 July 2017