Bid to rescue Ben Nevis weather data

- Published

The observatory was funded largely by the Scottish Meteorological Society

Scientists are seeking the public's assistance in rescuing a unique set of weather records gathered at the summit of the UK's highest mountain.

From 1883 to 1904, meteorologists were stationed atop Ben Nevis, logging temperature, precipitation, wind and other data around the clock.

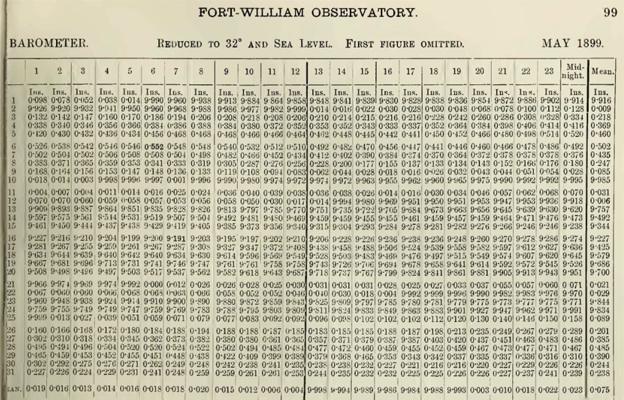

Their measurements are held in five big volumes that now need to be digitised to be useful to modern researchers.

The public can help with the conversion at the www.weatherrescue.org, external website.

It will involve copying tables into a database. Experts say the Ben Nevis records contain some fascinating reports on major storms from the period.

Prof Ed Hawkins: "Just a few minutes of someone's time can contribute to improving our knowledge"

It is not uncommon for the summit to be covered in a thick mist

There are also likely insights to be gained on the peculiarities of mountain weather. A fresh analysis could possibly lead to improvements in the performance of today's forecasting models.

"The data these men took is incredible, and it's arguably the most detailed mountain weather measurements we still have even today," said Reading University's Prof Ed Hawkins, who leads the Operation Weather Rescue: Ben Nevis project.

"And because the data was acquired over a century ago, it's a very good baseline from which to try to assess any changes that we've seen since then to our weather."

The Royal Society of Edinburgh published the data volumes between 1890 and 1910

The Ben Nevis observatory was set up to collect upper-atmosphere information. Nowadays, this function is performed by satellites, radars, and radiosondes (balloons). But in Victorian times, placing thermometers, rain gauges and anemometers on a tall mountain was the only systematic way to obtain the necessary data.

And at an altitude of 1,345m (4,411ft), the imposing Munro fitted the requirements perfectly.

The Scottish Meteorological Society largely funded the exercise, paying to put in a pony track, a low-rise building and a telegraph wire.

It also had a second station set up in Fort William at the base of the mountain. This allowed comparisons to be made with the weather at sea-level.

High ambition: The meteorologists of the day wanted to acquire data from further up in the atmosphere

Three or four men would man the summit observatory at any one time. One of these staffers would be the cook. They also had a pet cat.

Working in shifts, the meteorologists tracked hourly changes in temperature, pressure, rainfall, sunshine, cloudiness, wind strength and wind direction. And those parameters could be pretty brutal on occasions, with hurricane force winds and very heavy precipitation.

"At the start, when the snow was very bad, they had to tunnel their way out to make measurements," said Marjory Roy, former Superintendent of Met Office Edinburgh and author of the definitive book on the observatory - The Weathermen of Ben Nevis.

"They had a plan, though, for a tower - that's what you see in the photographs. The tower allowed them to mount an anemometer and other instruments, but it also allowed them to get out in winter when the snow was at roof-level."

The observatory closed when the sources of private and public funding would no longer cover the £1,000-a-year running costs.

Calum MacColl is a meteorologist who hails from Fort William, and recognises the Ben's many moods. He says modern models still struggle on occasions with their forecasts for the conditions on the highest ground, and he is hopeful the Victorian information can bring new benefits.

"In the last 10-20 years, the models have come on leaps and bounds and have a real good go at trying to mark out the complex orography (mountain topography). But they don't always get the peaks right and that can translate into inaccuracies in terms of the temperature, where the cloud base is going to be, and, somewhat more vital from the mountaineer's perspective - the strength of wind speed.

"It can be out by 30, 40 or 50 knots. Taking the old information into the new models could make a difference."

Looking southeast with fog trapped below a temperature inversion (warm air above cold)

In addition to their weather tables, the old volumes also contain some wonderful sketches of the Northern Lights and some of the optical effects that can be created when sunlight interacts with the likes of ice crystals or dust in the atmosphere. These aspects, however, are to be investigated separately.

Recovering old weather information is a daunting task. There are literally millions of records from centuries past that would undoubtedly aid modern scientific study if only they could be converted into a useable form.

The Royal Navy, for example, has a colossal archive of hand-written logbooks that will need to be transferred to digital form at some point.

Prof Hawkins says optical character-recognition tools can play their part in getting this old information into modern databases, but he believes citizen scientists are a powerful force.

"In part this is about trust," he told BBC News. "Do we trust a computer to read some of these old logbooks perfectly, or do we trust three sets of human eyes instead? And I think for accuracy, the human eyes still do it better."

Close to the edge: Hurricane force winds can blow at the summit

A companion station was operated in Fort William to collect complementary sea-level data

The Operation Weather Rescue: Ben Nevis project aims to have recovered two million data points from the mountain volumes by November.

The deadline coincides with the UK Natural Environment Research Council's free public event in Edinburgh in the middle of that month called UnEarthed. Staged at the Dynamic Earth venue, external next to the Scottish parliament, it will showcase wide-ranging endeavours of Britain's environmental scientists.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published18 March 2016