Neanderthal brains 'grew more slowly'

- Published

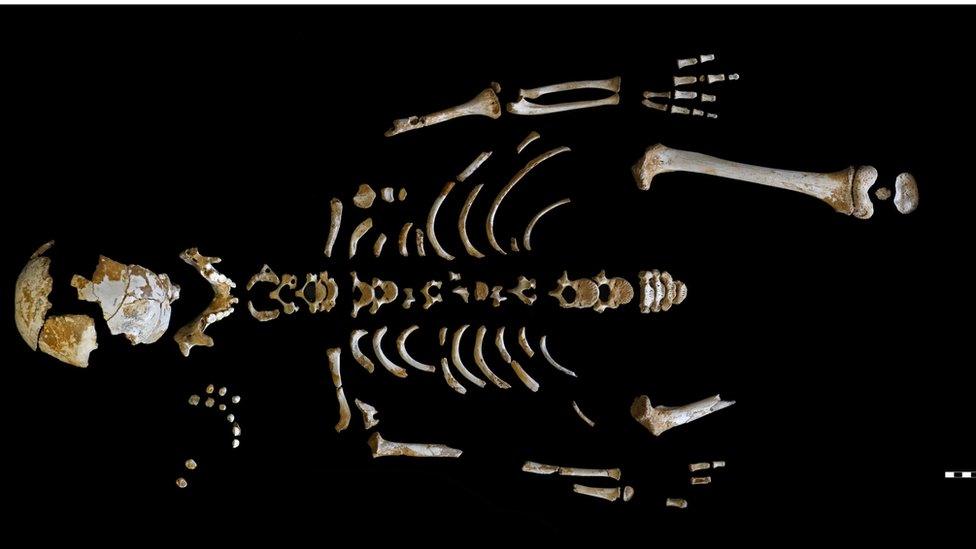

The skeleton of a boy that shattered our view of Neanderthal brain development

A new study shows that Neanderthal brains developed more slowly than ours.

An analysis of a Neanderthal child's skeleton suggests that its brain was still developing at a time when the brains of modern human children are fully formed.

This is further evidence that this now extinct human was not more brutish and primitive than our species.

The research has been published in the journal Science, external.

Until now it had been thought that we were the only species whose brains developed relatively slowly. Unlike other apes and more primitive humans, Homo sapiens has an extended period of childhood lasting several years.

This is because it takes time and energy to develop our large brain. Previous studies of Neanderthal remains indicated that they developed more quickly than modern humans, external - suggesting that their brains might be less sophisticated.

But a team led by Prof Antonio Rosas of the Museum of Natural Sciences in Madrid found that if anything, Neanderthal brains may have developed more slowly than ours.

"It was a surprise," he told BBC News. "When we started the study we were expecting something similar to the previous studies."

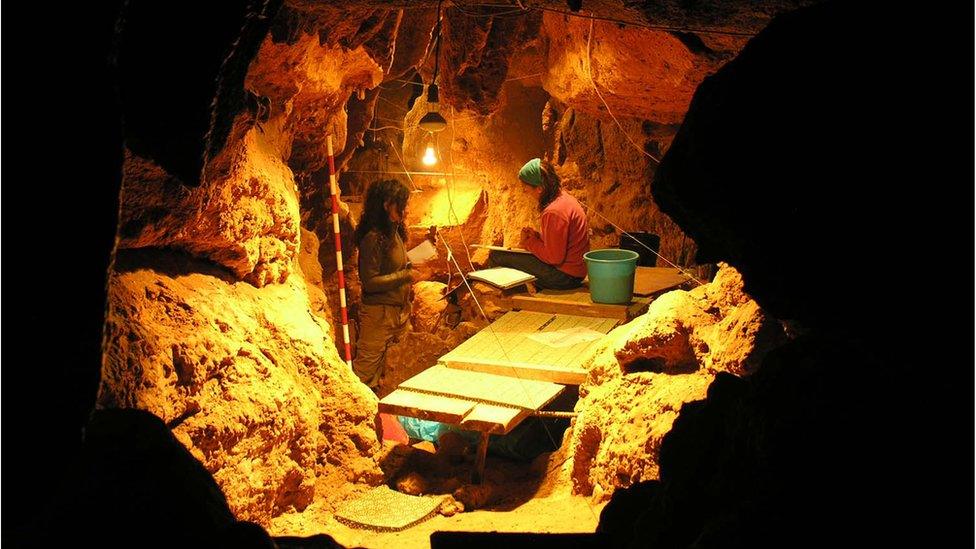

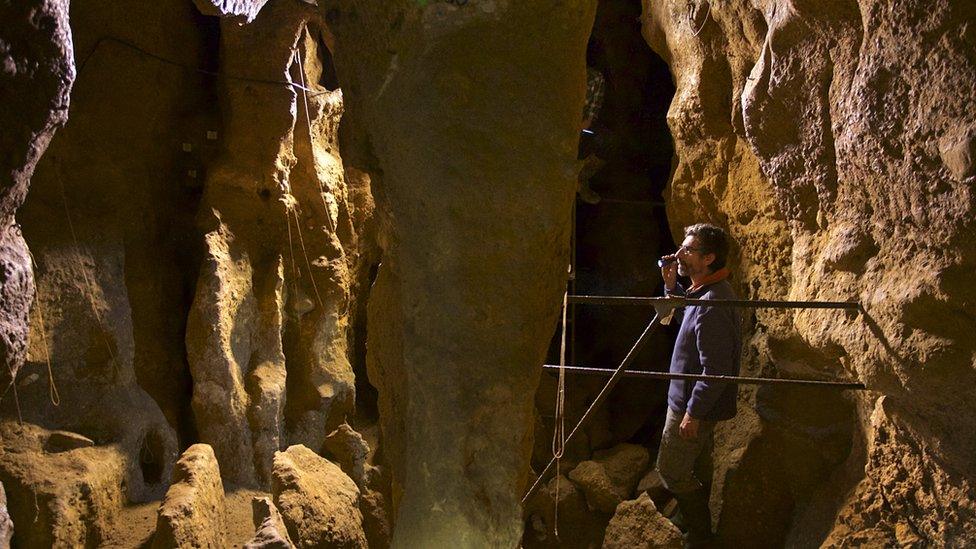

The remains were discovered inside the El Sidrón cave in Asturias, Spain.

Prof Rosas and his team believe they are right and the previous studies are wrong because for the first time they were able to study a relatively complete skeleton of a child at a crucial stage in their development.

It was of a boy, who was nearly seven-and-a-half years old when he died. His bones were found in the 49,000-year-old site of El Sidrón, in Spain.

The boy's remains are exceptionally well preserved and include a mix of baby and adult teeth, which enabled the team to accurately determine his age.

This brain is estimated to have been 87.5% of the size of an average adult Neanderthal brain upon death. A modern human child at the same general age would have, on average, a brain that was 95% the size of an adult's.

The researchers also found that some of the small bones forming the boy's backbone were not fused. In modern humans, these bones tend to fuse by the time children reach the age of six.

The researchers were surprised to discover that Neanderthal brains develop more slowly

According to Prof Rosas, the finding reinforces the idea that Neanderthals were not that different from us.

The brutish picture of Neanderthals is an old one. In the last few years there has been growing evidence to suggest that they were a distinct human species with some small differences. Now we can say that their growth pattern is similar to ours, too.

The finding raises the intriguing possibility that the Neanderthals' slightly slower brain development meant that their brains might have been more advanced than ours. But Prof Rosas prefers a more prosaic interpretation.

"Neanderthals have a larger brain and larger body and so it is logical to think that the brain of the Neanderthal continues to grow for a little longer to allow their brains and bodies to get to their adult size," he explained.

Before this finding, scientists believed that modern humans were the slowest growing species. Now we know that Neanderthals took slightly longer, suggesting that both species inherited this growth pattern from a now extinct common ancestor.

Follow Pallab on Twitter, external

- Published27 December 2010