Satellites spy Antarctic 'upside-down ice canyon'

- Published

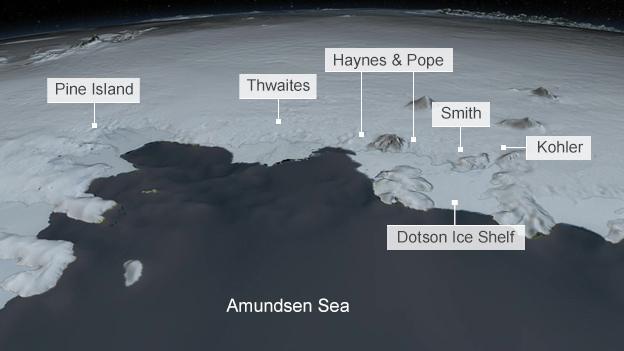

Graphic: Some fast-thinning glaciers drain into the Amundsen Sea

Scientists have identified a way in which the effects of Antarctic melting can be enhanced.

Their new satellite observations of the Dotson Ice Shelf show its losses, far from being even, are actually focused on a long, narrow sector.

In places, this has cut an inverted canyon through more than half the thickness of the shelf structure.

If the melting continued unabated, it would break Dotson in 40-50 years, not the 200 years currently projected.

"That is unlikely to happen because the ice will respond in some way to the imbalance," said Noel Gourmelen, from the University of Edinburgh, UK.

"It's possible the area of thinning could widen or the flow of ice could change. Both would affect the rate at which the channel forms.

"But the important point here is that Dotson is not a flat slab and it can be much thinner in places than we think it is and much closer to a stage where it might experience major change."

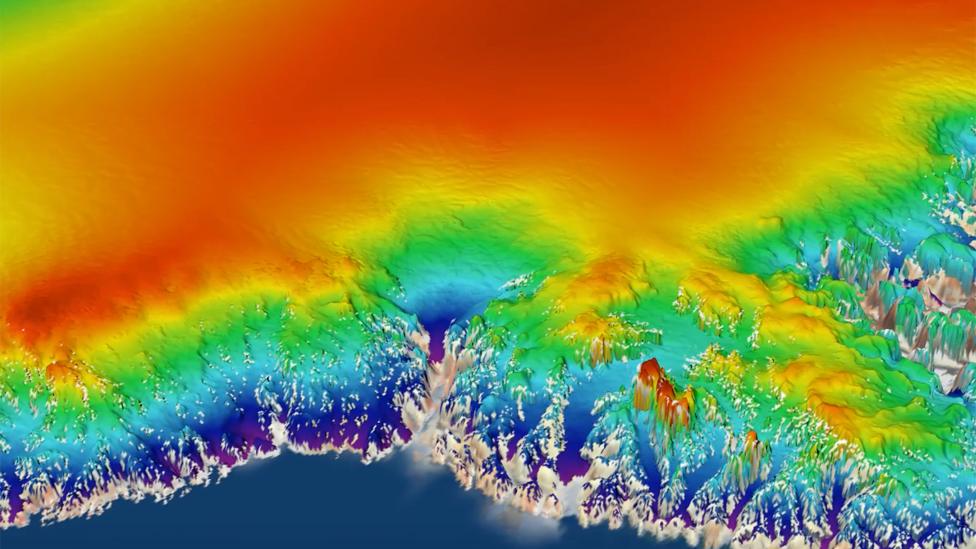

This animation shows how warm water gets under and melts the ice shelf

Dr Gourmelen's new study, published in Geophysical Research Letters, external, uses the European Space Agency's Cryosat, external and Sentinel-1, external spacecraft to make a detailed examination of the thickness and movement of Dotson.

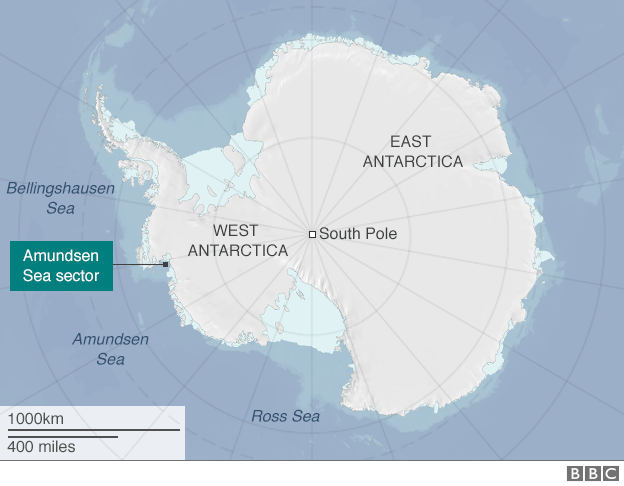

The 70km by 40km ice shelf is the floating projection of two glaciers, Kohler and Smith. As they stream off the west of Antarctica, their fronts lift up and join together, pushing out over the Amundsen Sea.

The shelf acts as a buttress to the ice behind. If Dotson were not present, Kohler and Smith would flow much faster, dumping more of their mass in the ocean, contributing to sea-level rise.

Satellites have long tracked the behaviour of the shelf, but in Cryosat in particular researchers now have an altimeter instrument that is able to retrieve much higher-resolution elevation information than ever before.

Ice shelves are the floating protrusions of glaciers flowing off the continent

Taking the period of its observations from 2010-2016, Dr Gourmelen's team can see that Dotson's surface is lowering on average by about 26cm per year, which suggests the roughly 400m-thick shelf as a whole is thinning by about 2.5m per year.

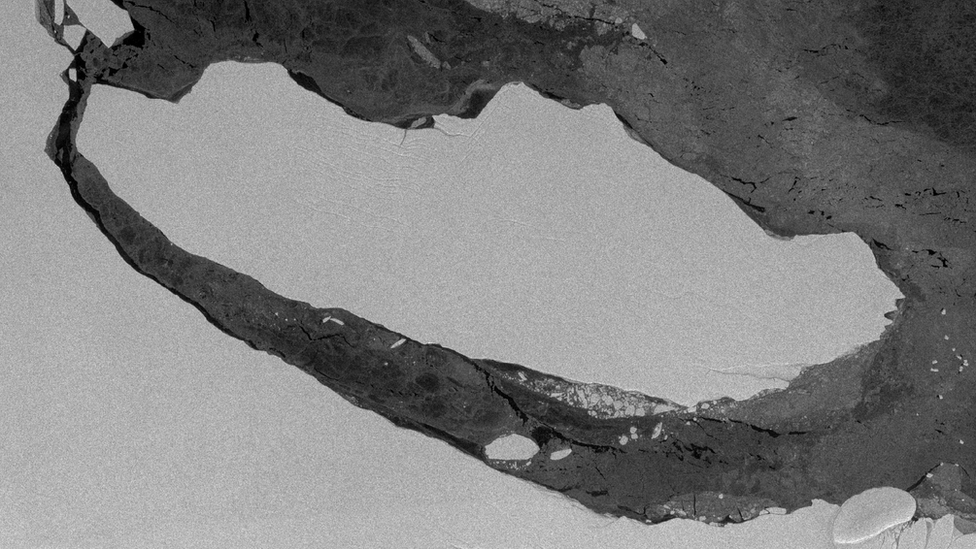

But Cryosat's sharper vision also reveals that this thinning is concentrated at a surface depression that is roughly 5km wide and 60km long.

It extends from the point where the glacier ice starts to float as it comes off the land, all the way out to the front edge of the shelf where icebergs are calved into the ocean.

What the team is able to show is that this surface depression corresponds to an incised canyon on the underside of the shelf.

The average width of this inverted gorge is 10-15km but it cuts up into the shelf by as much as 200m in places. The Edinburgh-led group says all the evidence suggests warm water from the deep ocean around Antarctica has got under the shelf to melt out the canyon.

"We say warm; it's 0.6-0.7 degrees," explains Dr Gourmelen. "It makes its way into the cavity under the shelf along a trough to the grounding line, and then it starts to rotate clockwise and rises. And it comes out on the west side. That's where we see the thinning and the basal melt."

Artist's impression: Cryosat, with its radar altimeter, was launched into orbit in 2010

This export of fresh melt-water from the underside of the shelf carries with it a lot of iron from rocks scraped from the continent, and drives strong growth in plankton and other biological activity in front of Dotson.

Just a simple forward projection using the pattern and rates of thinning observed by Cryosat and Sentinel-1 in this study would lead to complete melt-through of Dotson's front in 20 or so years, and its rear in about 40 years.

That is on the order of 170 years earlier than Dotson would thin to zero using the ice-shelf-averaged thinning rate. But as previously stated - the shelf is not a static structure and it will react to the formation of the canyon.

"An ice shelf can be a complicated thing," says co-author Prof Andy Shepherd from Leeds University and principal scientific adviser on the Cryosat mission.

"As you thin them it reduces the traction on the feeding glaciers, allowing those glaciers to speed up; and as they speed up, they should put more ice into the ice shelf so that it thickens again. It is supposed to be a stabilising effect."

Prof Shepherd said a new high-resolution swath mode used by Cryosat at Dotson was now being deployed elsewhere around Antarctica to look for more patterns of enhanced thinning on other ice shelves.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published9 October 2017

- Published10 July 2017

- Published12 May 2016