Botanical exploits: How British plant hunters served science

- Published

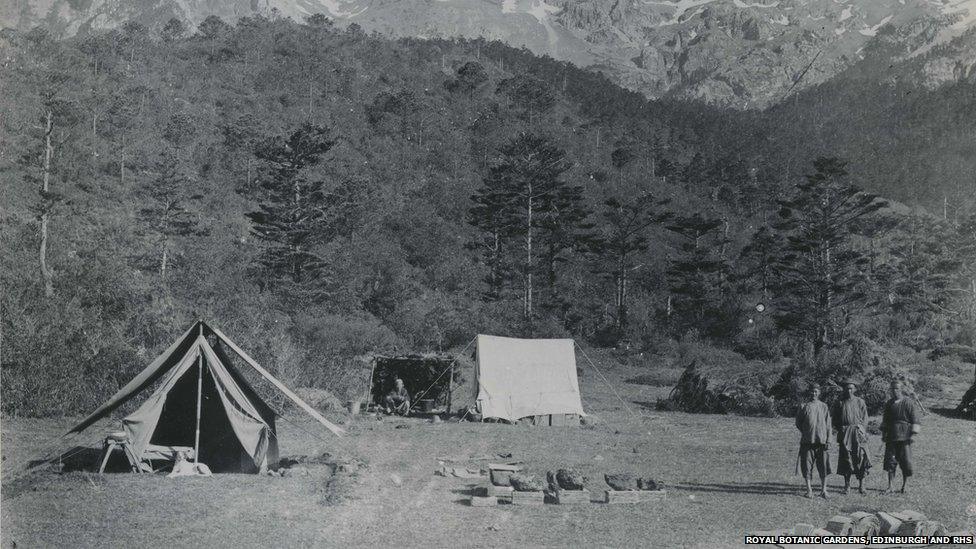

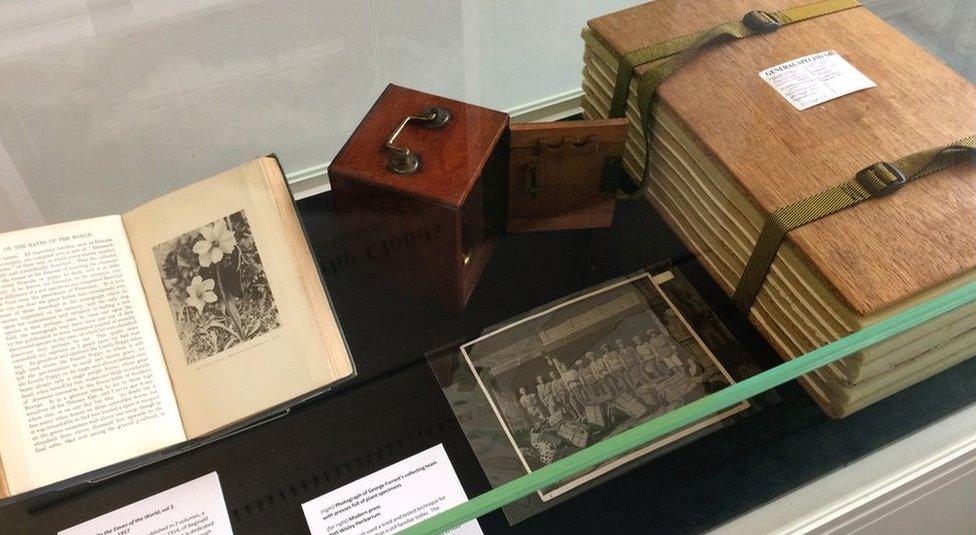

Plant specimens are pressed under large rocks at George Forrest's campsite in Lichiang Range

In a corner of the Yorkshire Dales, far from the beaten track, you might stumble on the peaceful village of Clapham.

Now known as a stop-off point for exploring the dales, it was once the home of a rock garden full of plants never seen before in the Western world.

Legend has it that the Edwardian plant-hunter Reginald Farrer loaded a shotgun with seeds collected on an expedition to Ceylon and fired them into a rock cliff and gorge.

While the rock garden is long gone, you can still see other specimens brought back by Farrer dotted around the woods beside his family home.

Camellia x williamsii. The plant collected in the wild by George Forrest was one of its parents

The flamboyant rhododendrons, lilac-flowered honeysuckles and sweetly fragranced viburnums are floral reminders of his far-flung travels.

Farrer was among the early British plant-hunters who risked death to explore the botanically rich interior of China in the name of science.

"It's a fascinating period when China was opening up to botanists and explorers so that we could see their fauna and flora,'' says Sarah McDonald, Heritage Collections Manager at the Royal Horticultural Society (RHS).

''They all had this love of travel, this love of exploration, an absolute love of plants as well.

''And to be the person who first found a particular plant and to have that plant named after yourself or to be able to recommend who it was named after was what really drove them, I think.''

Into the wilderness

Reginald Farrer (1880-1920) was one of four 20th Century botanists who made expeditions to then remote parts of China to discover and bring back plants.

He and his contemporaries - George Forrest (1873-1932), William Purdom (1880-1921) and Frank Kingdon-Ward (1885-1958) - are remembered in a new exhibition at the RHS Lindley library in London.

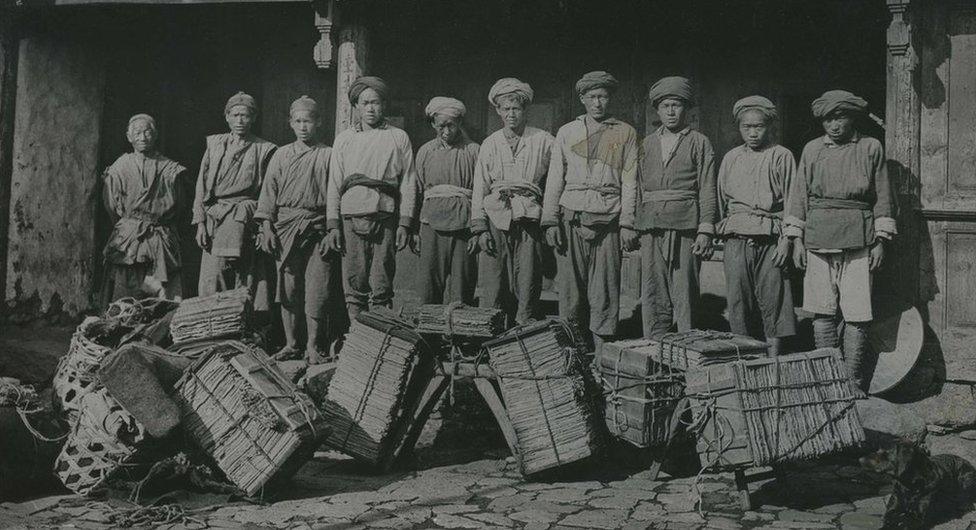

George Forrest's team with presses full of blotting paper and specimens

Photographs, an original plant press and books published by the explorers are on display in the library, which holds unique collections of early printed books on botany.

In the archives, Sarah regales me with tales of the intrepid four.

''There were all sorts of perils and disasters; from weather, storms, earthquakes through to tropical diseases,'' she explains.

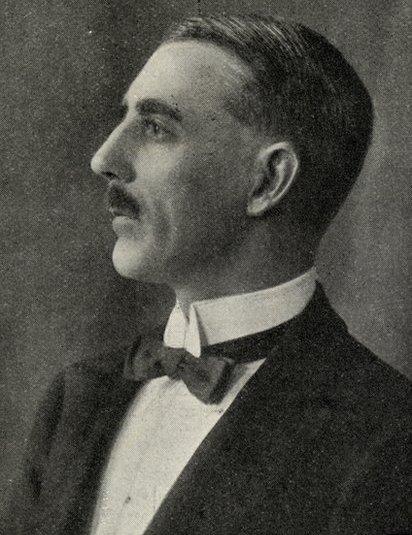

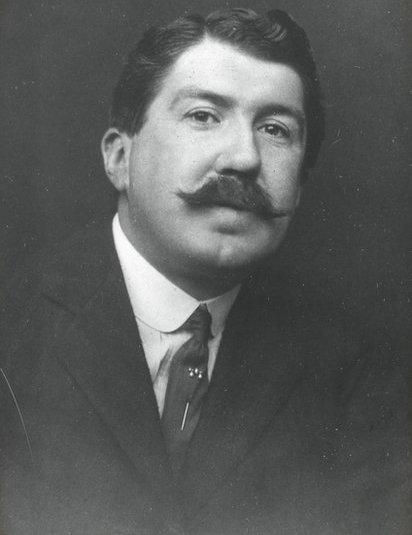

George Forrest: The Scottish botanist became one of the first explorers to Yunnan province

"George Forrest on his very first expedition in 1904 escaped with his life only narrowly from Tibetan monks who were rebelling against Chinese missionaries and were rampaging through the countryside.

"The two missionaries that he was travelling with died a horrible death but fortunately after a week travelling on his own he managed to get to a safe village, barefoot, almost starving, but he got home."

Forrest lost all of his specimens, but continued his expeditions, carrying out a further six, to Upper Burma, eastern Tibet and Sichuan province.

He spent months in the wilderness, navigating sheer cliffs and makeshift bridges across deep gorges.

His last expedition proved to be his most successful, but, in 1932, he collapsed and died of a heart attack outside the town of Tengyueh.

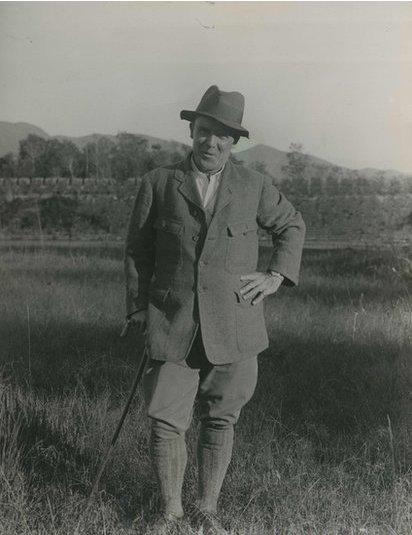

Frank Kingdon-Ward was born in Manchester in 1885

Forrest collected over 31,000 specimens from China, discovered more than 1,200 plant species new to science and had more than 30 taxa named after him.

They range from large magnolia trees with water-lily-like flowers, to spectacular camellias and more than 50 types of primula.

Over a similar time period, Farrer introduced many alpine species from China, Tibet and Upper Burma. He travelled with William Purdom, an English plant explorer who had been trained at Kew.

"Purdom was a very shy, retiring chap; we don't have very much from him," says Sarah McDonald.

"He didn't keep diaries or journals, but he was a great support to Farrer. Farrer probably couldn't have operated without him in the field.

"Purdom knew Chinese, he knew the local people, he was very much liked by them, so he really supported Farrer's expedition."

Reginald Farrer: He died in mysterious circumstances in the mountains of Burma

In 1914, Purdom and Farrer set out on an ambitious expedition to Tibet and northwestern China.

Their two years of adventures are documented in Farrer's books, On the Eaves of the World (1917), and The Rainbow Bridge (1921), published after his death in the Burmese mountains.

Two miracles

Frank Kingdon-Ward, son of a botany professor, was perhaps the most prolific of the four plant collectors.

"He carried out over 20 expeditions in total - not all in China; he travelled all over, in India as well and Assam Himalayas, and really his first love was exploration," says Sarah McDonald.

Kingdon-Ward frequently cheated death on his travels. Once, lost in the jungle, he survived by sucking the nectar from flowers. Another time, a tree fell on his tent during a storm, but he crawled out unscathed. And he survived falling over a precipice only by gripping a tree long enough to be pulled to safety.

In a letter to his sister, he wrote: "If I survive another month without going dotty or white-haired it will be a miracle; if my firm get any seeds at all this year it will be another."

Many of the plants brought back by Forrest, Farrer, Kingdon-Ward and Purdom can be seen at RHS gardens, both as living specimens and in the Herbarium at RHS Wisley.

Farrer's books can be seen at the exhibition

More than 80,000 preserved plants, which are used for scientific study, are filed away in numerous cupboards.

The specimens collected by early plant-hunters are an important scientific legacy.

Yvette Harvey, Keeper of the Herbarium, says plant collecting remains important because we haven't yet collected every single plant in the world.

"It's extremely important to have a specimen that everyone can refer back to in the future," she says.

"Our collection is steadily increasing by about a thousand specimens a year."

Plant pilgrimage

Some of the first plant-hunters in the field were commissioned by the RHS, and this work continues today. More than 100 years since the men set off on their travels, the RHS is calling on horticulturists to start their own plant-finding missions through its bursary scheme.

Recently funded missions include expeditions to South Africa in search of red-hot pokers and searching for rare azaleas in Japan.

Wisley's famous berberis

After my visit to the Herbarium, Yvette Harvey leads me through the gardens on a plant pilgrimage of our own.

It's a sunny winter morning and children bundled up in coats, hat and gloves dart along the paths or point up at the large cranes on the skyline that are carrying out a multi-million-pound development scheme.

Tucked away in a bed near the lake is a large berberis shrub descended from the specimen collected on the Farrer-Purdom expedition. It's not showy and you could be forgiven for strolling by without giving it a second glance.

But it's thanks to collectors like Farrer and Purdom that plants such as these grace most British gardens today.

Collecting in the Clouds: Early 20th Century Plant Discoveries runs until Friday 2 March at the RHS Lindley Library in London.

Follow Helen on Twitter, external.