Finnish start-up ICEYE's radical space radar solution

- Published

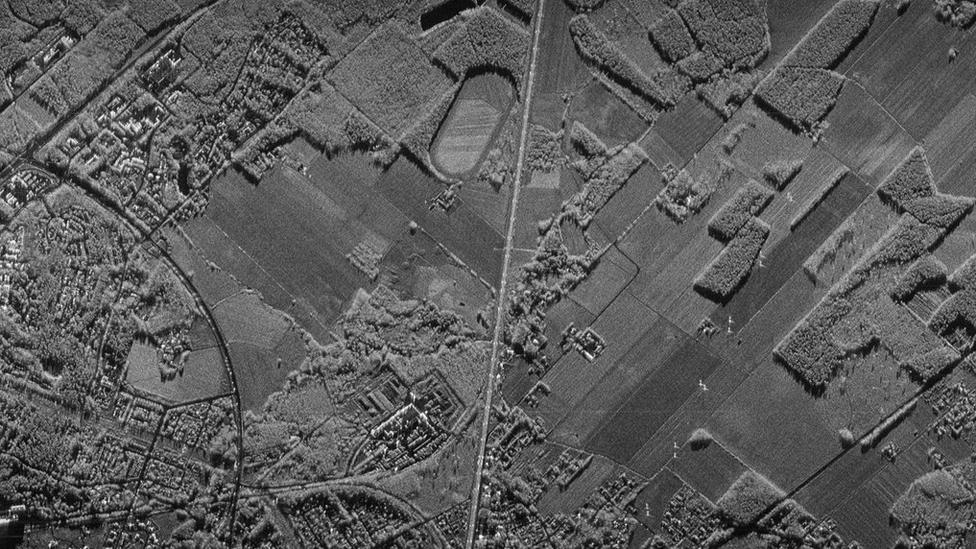

Artwork: The ICEYE satellites would see features on the ground as small as 3m across

Big things sometimes come in small packages. That's the hope of Finnish start-up ICEYE, who are about to see their first satellite go into orbit.

The young company are making waves because they're attempting what no-one has dared try before; indeed, what many people had previously said was impossible.

ICEYE, external aim to launch a constellation of sub-100kg radar micro-satellites that will circle the Earth, returning multiple pictures daily of any spot on the globe, whether it's dark or light, good weather or bad.

The special capability of synthetic-aperture radar (SAR) satellites to sense the planet's surface whatever the conditions is loved by government and the military, obviously - and they make sure they always have access to this kind of imagery.

But here's the rub: the spacecraft that gather this sort of data have traditionally been big, power-hungry beasts.

The EU's mighty Sentinel-1 series of spacecraft, for example, weigh well over two tonnes each, and their transmit/receive radar antennas are 12m long. They also cost, external a couple of hundred million euros a pop.

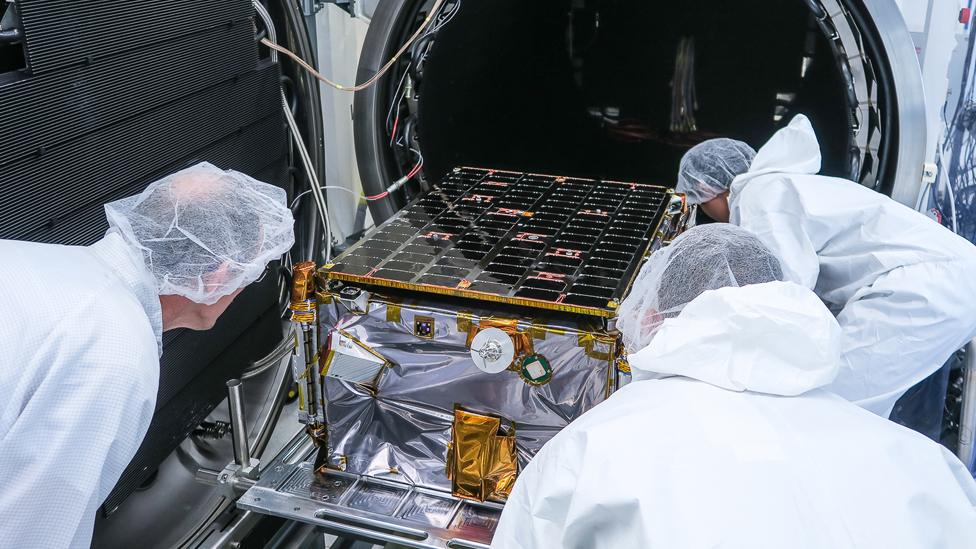

ICEYE's new kid on the block, on the other hand, weighs less than the fuel carried aboard each Sentinel and fits in a box that's 80cm by 60cm by 50cm.

The antenna, once unfolded in orbit, is a mere 3.5m in length.

Rafal Modrzewski: "When we come with a three-hour revisit time, it will change the game"

"When we started this, we'd go to people and say: 'Hey, why not build a small SAR satellite that costs just a couple of million?'. And they'd go: 'Because that's impossible'. And then we'd say: 'But why?'. And they couldn't answer that," recalls company CEO and co-founder Rafal Modrzewski.

So how have ICEYE shrunk the SAR package? The answer broadly has two parts.

The first explanation is in the acronym COTS, which has become the mantra for all the so-called "new space" companies.

The ICEYE team is exploiting the greatest possible use of "Commercial Off The Shelf" components in their satellites, rather than the special, space-rated components found in conventional spacecraft.

"Space-rated components may have tremendous reliability, but they're very immature in their capability," says Rafal. "When you move to COTS, you're suddenly a decade ahead. You get access to the very latest capabilities.

"And the change comes both in cost and in size because COTS components have been miniaturised to fit inside your phone, literally. We are using the same components."

COTS components significantly reduce the size of the package... and the cost

Of course, you carry extra risk in not using parts that have been built specifically, and proven, to operate in space. The environment up there is harsh and unforgiving.

But if your plan is to launch a constellation of satellites you can tolerate that because if one spacecraft fails, there are still the others to pick up the slack.

And by flying a network of satellites, you also get to the second part of ICEYE's solution - which is power management.

The big satellites image for long periods during an orbit. Flying as a single mission or maybe as just a pair of satellites, this "always on" approach is necessary to acquire a meaningful volume of data.

But that has consequences for how a spacecraft gathers and stores its solar energy to operate the radar instrument, and how the system dissipates heat - all of which impact on size.

The beauty of radar is that it sees the surface even at night and through cloud

ICEYE's alternative is the short duty cycle. Each of its micro-SARs will be imaging for just a few minutes on an orbit, which makes these power issues easier to handle. And, once again, with lots of satellites, it is possible still to cover the same amount of ground - and more, and image the same spot more frequently.

"Our 18 satellite constellation gets you London or Paris eight times a day. The 30 satellite constellation provides you London/Paris 15 times a day. That's where it really starts to become interesting," Rafal told me.

"Right now we're using SAR data to try to track illegal fishing vessels or to look for refugee boats in the Mediterranean, but how can you do that if you only see the same spot every three days?

"What if these boats pass through in the time in between. And that's what happens: these people know there is a satellite that's going to pass overhead, and when it does they carry on with what they were doing.

"It's the same with oil spills: you'll see the slick but the ship responsible is gone."

The first microsatellite, ICEYE-X1, launched on Friday.

The ICEYE satellite's radar antenna unfolded in an anechoic chamber

It is the pathfinder that must prove what have been up until now just "forward looking statements".

But if ICEYE can get sufficient numbers of further spacecraft into orbit then it has the opportunity to open new markets based on rapid, repeat imagery.

In the first instance, this will be used for simple change detection. Has that forest been felled? Have those trucks moved? How many ships are in port? Where are the icebergs? (Ice monitoring was an original motivation for the company, hence the name).

Seraphim, the London-based venture capitalists, external, have invested in the company and are excited to see what it can achieve.

"We believe ICEYE is going to be a very valuable business," said Seraphim CEO Mark Boggett.

"So often you've heard the incumbent space industry say of new space companies: 'No it can't be done, it can't be done. Actually, yes it can'.

"We think ICEYE can expand markets with a constellation that re-visits the same spot many times a day and delivers a product at a price point that will be affordable to many different 'verticals'.

"Ultimately, that increases the cake for everyone, including the incumbents."