The whales that have returned to South Georgia's killing waters

- Published

A southern right whale raises its head out of the water off South Georgia

It's kind of shocking that right whales should be so-called because they were the "right whale to kill".

Slow surface-dwellers that were curious of humans and boats - their numbers started to tank long before the modern era of commercial whaling, post-1900.

The catch techniques of Basque fishermen in the 16th and 17th centuries were tragically effective.

The animals were particularly vulnerable because of their of calving habits, says Dr Jennifer Jackson from the British Antarctic Survey (BAS).

"A very vicious type of whaling was enacted on them - what was termed 'bay whaling'.

"Right whales had very high fidelity to certain areas, to certain bays, and they would return every three years to produce young. The whalers would just sit in the bay and knock them out when they returned. And when no more came back, the whalers simply moved on to the next bay."

There are three species of right whale - two in northern waters, in the Atlantic and Pacific; and one in the southern hemisphere.

The northern species are in deep, deep trouble still. Individuals can be counted in just the hundreds, and ship strikes are killing the animals at an unsustainable rate.

Fortunately, the southern right whale (Eubalaena australis) is estimated to be doing much better with its various populations adding up to more than 7,000.

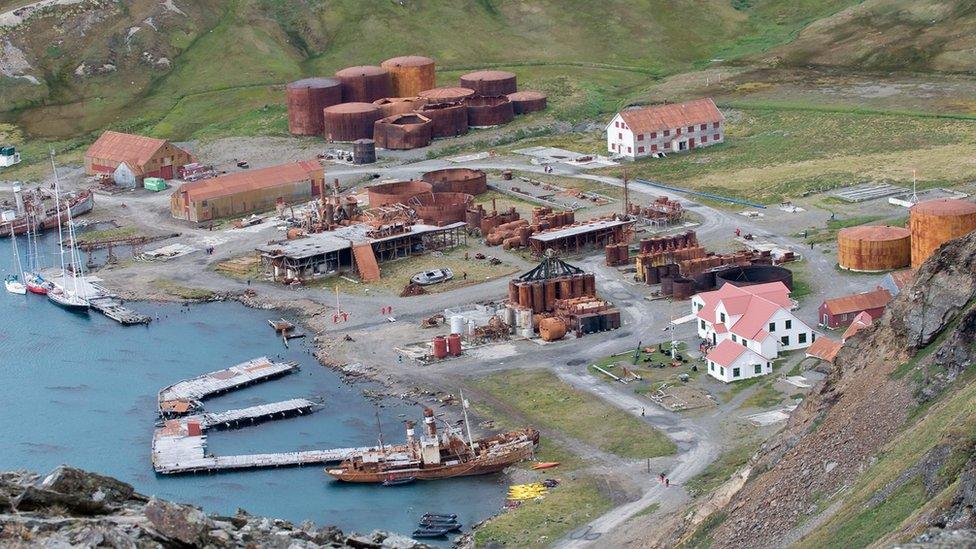

Commercial whaling at South Georgia ended in the 1960s - but the scars remain

Just how well they are recovering from more than 300 years of exploitation is not a straightforward statement to make, however. The waters they occupy towards the bottom of the planet are vast, and that poses very obvious challenges for those who would undertake a survey. But Dr Jackson is undaunted.

She leaves this week with seven other scientists for a research cruise, external based out of South Georgia, external.

The area around the British Overseas Territory is an important feeding ground for the animals. The aim is to count the whales and assess their health.

The venture is noteworthy, not least because it will be the first such survey conducted in the vicinity of the island since its whaling stations were abandoned in the late 1960s.

"South Georgia was once the epicentre of commercial whaling," says Dr Jackson. "When you consider the havoc that place created - they killed more than 176,000 whales within a day's sail - it's amazing no-one's gone back since to do a proper assessment of how whales are doing now."

Dr Jackson's team will be working off the appropriately named "Song of the Whale, external", a 21m-long cutter owned and operated by Marine Conservation Research International.

The scientists will be using acoustics to find the animals, and then photographing their lumps and bumps. The pattern of hard skin patches, or callosities, on the head of a right whale is a unique identifier.

If possible, the team will also try to tag some animals with satellite trackers, and take skin samples to do DNA analyses. The animals' genetics hold clues about population history and the relationships between different groupings.

Dr Jennifer Jackson: "We want to find out how they're doing, how they're recovering"

One innovation that has seen increasing use in recent years is the "whale breathalyser".

A hexacopter collects blow from a North Atlantic right whale in Cape Cod Bay

This involves flying a drone over the blowhole and catching a sample on a petri dish of whatever is vented by the animal.

It is a way of determining a whale's microbiome - the family of bacteria, fungi and viruses held in the respiratory system. You can tell a lot about the health and condition of humans just from their breath. Likewise with whales.

The Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), external in the US will be analysing the samples gathered by the South Georgia team. WHOI has already examined many other samples from right whale populations across the globe - from calving grounds and from feeding grounds.

"Thus we will be building both a baseline data-set for the right whale respiratory microbiome, and be able to compare between individuals showing different body conditions in each habitat," says WHOI's renowned right whale expert, Dr Michael Moore.

One major concern currently in the southwest Atlantic is the large number of dead calves washing up on Argentina's coast.

South Georgia is famous for its wildlife. It supports countless birds, seals and penguins

Various theories have been proposed, but Dr Jackson thinks climate factors may well be in play.

The right whales around South Georgia are expected to feed mainly on the stream of krill brought up on currents from the Antarctic Peninsula. If that conveyor of crustaceans is denuded, perhaps because of some climate shift or oscillation, then this is likely to impact the breeding success of these animals.

"BAS scientists have studied the krill relationship for decades as it affects seals and penguins - but not whales. However, we already think there is a bit of a relationship there," says Dr Jackson.

"And, obviously, as the climate changes and krill availability becomes more unpredictable, we expect we'll see more perturbations for right whales in terms of their calving.

"So, getting a good baseline understanding of how they're using South Georgia waters - where they're feeding and how many there are - is really important for monitoring changes in the future."

The BAS project, external is being run over two years, funded by the EU and the UK's Darwin Initiative, external. As well as WHOI, collaborators are also drawn from the University of St Andrews, external and Instituto Aqualie, a Brazilian non-profit that specialises in satellite-tracking whales.

Tourists who happen to be in the region can help by photographing any whales they see and uploading the pictures to www.happywhale.com, external.

Callosities will be home to lice and worms, but the whales do not seem unduly worried by them