NZ rocket launch heralds new wave

- Published

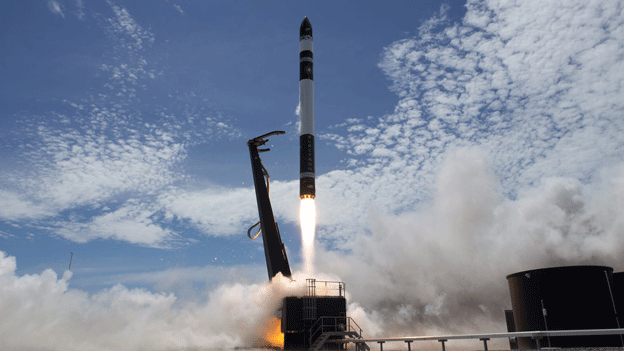

The Electron launches from New Zealand's Mahia Peninsula in the North Island

Twenty-eighteen is shaping up to be a fascinating year for the rocket business.

All eyes currently are on Florida as we await the debut of the Falcon Heavy, external, the SpaceX company's bid to claim the title of "the most powerful launch vehicle on the planet".

But we're also avidly watching the other end of the lifting scale, and the flurry of small launchers that are in the process of making their way to market.

Silicon Valley start-up Rocket Lab announced its intent at the weekend with a fully successful launch from New Zealand, external of its Electron vehicle, popping three cubesats in orbit.

A maiden flight last May had to be terminated a few minutes after lift-off, but Sunday's flawless mission was clear demonstration that Rocket Lab is now ready to enter commercial service. And there'll be others following hard on the heels of the US/NZ operation.

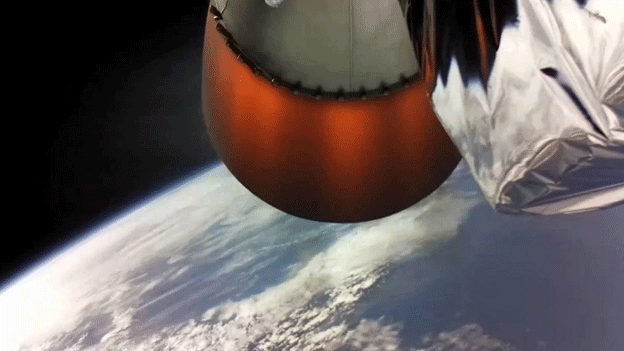

The Electron vehicle looks down on Earth after Sunday's successful flight

Sir Richard Branson has a low-cost satellite launcher going through the final phases of ground testing before attempting its first outing.

Called simply enough LauncherOne, this 21m-long booster will be carried to cruising altitude by an old Virgin Atlantic jumbo, before then being released to power skywards.

The rocket is designed to take spacecraft weighing up to 300-500kg into low-Earth orbit. If analysts are correct, the future will be dominated by satellites in this class, and smaller.

Paris-based market-watchers Euroconsult reckon more than 6,200 small satellites will need rides over the next decade, external, and LauncherOne, Electron and others will all vie to be the taxi of choice.

For years, the LauncherOne project lived in the shadow of Sir Richard's other space project - his Virgin Galactic tourist rocket-plane. But then in March last year, LauncherOne was cleaved into a separate entity with its own company profile called Virgin Orbit, external.

Will Pomerantz: "Small satellites have traditionally been treated literally as second-class citizens"

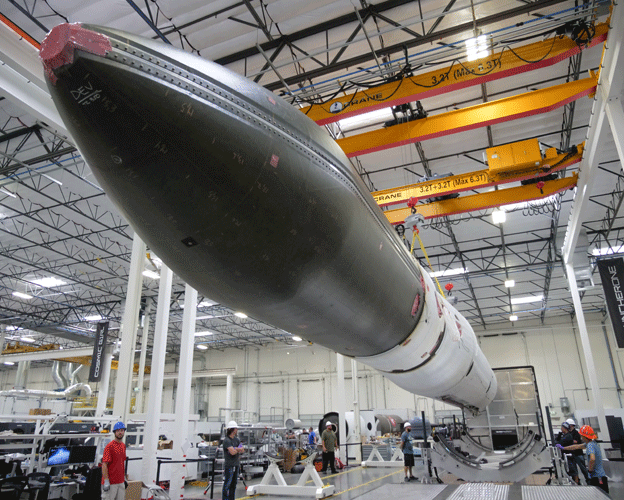

It occupies a 16,000-sq-metre design and manufacturing facility in Long Beach, California, on the edge of the airport where McDonnell Douglas used to despatch its newly built planes.

Walking around Virgin Orbit, as I did in the autumn, you see a mass of tanks, composites and propulsion motors in various stages of dress.

The current timeline calls for the first fully assembled rocket to be flight-tested in the first six months of this year. Assuming that goes well, the production and flight rate will be ramped up sharply.

There is capacity to make 24 LauncherOnes a year in Long Beach. That's two missions a month.

If the projections about the coming wave of small satellites are correct, that number of 24 seems almost too few!

The Long Beach factory hopes to be turning out 24 vehicles a year

There's definitely a new entrepreneurial spirit out there that's taking advantage of technologies proven with consumer electronics like cellphones to make very capable spacecraft in compact packages - to relay telecommunications, take Earth observation pictures and to gather weather data.

Earlier this month, I wrote about a novel radar micro-satellite and a rapid-build spacecraft that will make movies from orbit.

These and other "new space" products will feature in constellations of breathtaking size.

It's this expected bonanza that has prompted the rush of new, small rocket concepts. Just how many small rocket projects are actively in development is hard to say, but it certainly numbers in the tens.

They won't all succeed, of course; and the long-established aerospace companies with their much larger vehicles are bound to react. They're already trying.

It's now commonplace, for example, to see bigger rockets pump out small satellites after they have dropped off a primary payload in orbit. But Will Pomerantz, Virgin Orbit’s vice president of special projects, says the new class of small-sat operators are no longer prepared to play second fiddle.

Jim Cantrell: "We're focussed on breaking down the barriers to space access"

"Right now, if you had a satellite already built and you had the money to buy a launch - you'd still have to wait 24 months typically to get that satellite into orbit," he told me.

"And if you haven't built a big satellite and paid for the whole launch yourself, you're really at the mercy of whoever has booked that ride and has allowed you to come along as a hitchhiker.

"So, if their schedule changes, then so does yours; and if their plans change about which orbit they're going to, then so do yours; or you go back to the end of the queue and start over.

"We're offering those customers who've been used to being literally second-class citizens the chance to be the driver of the car."

But it's not just the flexibility that this new breed of small rockets is playing off - it's also price, says Vector chief executive Jim Cantrell.

After a couple of limited-altitude flights in 2017, his Arizona-based company, external's rockets will likely make their orbital debut this year as well.

Vector is offering rides for payloads weighing up to some 50kg that cost no more than $1.5m.

Part of the reason small rockets carry such a low sticker price has to do with their simple designs, says Cantrell, and the old, established rocket manufacturers, with their bloated supply chains, simply won't be able to compete on the same level.

"The smaller it is, the simpler you can make it," he told me.

"Our rocket, for example, has 1,000 parts, and SpaceX's rocket - we estimated at about 26,000 parts. Think about the supply chain behind each of those parts. Each of those parts has someone who's making something or a machine is making it.

"It's a combination of all these things that's really made it possible to sell rockets for what seems like a ridiculously low price."

A Vector-R rocket launches from the US state of Georgia in 2017

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external