SpaceX launches broadband pathfinders

- Published

- comments

The early morning launch had to go off at a very specific time

SpaceX launched again on Thursday - this time to put a Spanish radar satellite above the Earth.

But there was a lot of interest also in the mission's secondary payloads - a couple of spacecraft the Californian rocket company will use to trial the delivery of broadband from orbit.

SpaceX has big plans in this area.

By sometime in the mid-2020s, it hopes to be operating more than 4,000 such satellites, linking every corner of Earth to the internet.

Wednesday's flight was the first for SpaceX since the dramatic debut on 6 February of its Falcon Heavy - the world's most powerful launcher.

This time, it was the turn of the smaller workhorse, the Falcon-9.

It lifted clear of the Vandenberg Air Force Base on the US Pacific west coast at exactly 06:17 (14:17 GMT).

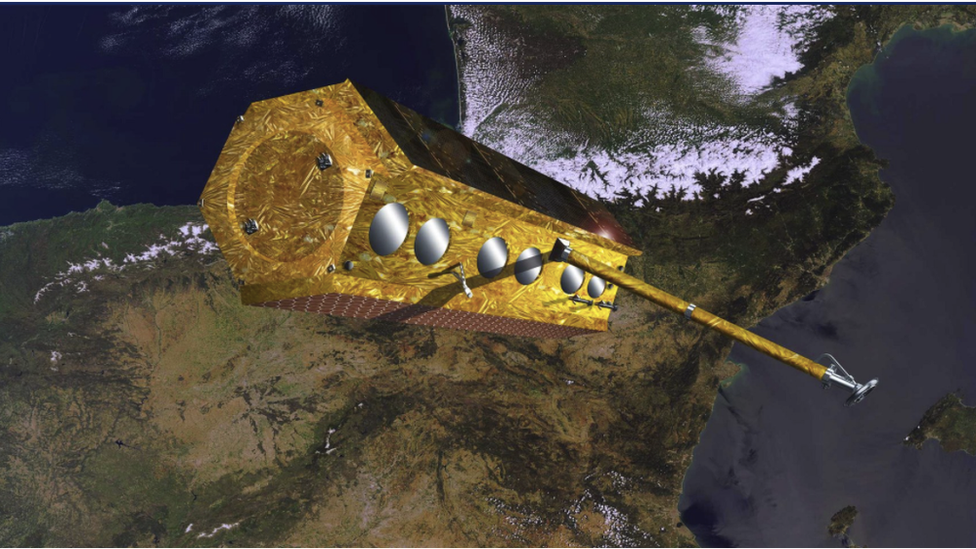

An artist's impression of the PAZ radar imaging satellite above the Earth

The precise timing was needed to ensure the PAZ radar satellite, to be managed by Madrid-based Hisdesat, was dropped off in the right part of the sky.

The new Earth observer is to team up with a German pair of spacecraft, Tandem-X and TerraSAR-X, which are already in orbit.

As a trio they will image the planet's surface, seeing features as small as 25cm, even when there is heavy cloud in the way.

The ascent to orbit and release of the PAZ platform took just 10 minutes. SpaceX made no attempt to recover the first-stage booster from the Falcon-9, allowing it to fall into the ocean. The rocket segment had previously flown last year.

Of more interest to SpaceX on this occasion was the release of the pathfinder satellites for its planned Starlink broadband network.

In 2016, it filed an application with the Federal Communications Commission in the US for a licence to operate a "mesh network" in the sky consisting of 4,425 satellites arranged in 83 orbital planes.

These spacecraft would be positioned at altitudes ranging from 1,110km to 1,325km, and transmit in the Ku and Ka portions of the radio spectrum.

The company would like also to put up an additional 7,500 satellites that would sit under the initial set and transmit in the V-band.

The two SpaceX satellites either side of the adaptor that held them in the rocket

The idea is that Starlink would deliver terabits of throughput, with all spacecraft linked so that bandwidth could be focussed on those regions where it was needed most.

Wednesday's Falcon-9 took up the Microsat-2a and Microsat-2b testbeds (CEO Elon Musk dubbed them Tintin A & B in a tweet).

The pair are identical - with a bus, or chassis, being slightly less than 1 cu metre, and having two 8m-long solar wings; and weighing roughly 400kg.

The Microsats are intended to prove all the different design elements, such as the antenna that will relay the data traffic.

If all proceeds as it should, SpaceX will aim to start deploying Starlink's satellites in batches over the next few years.

The Falcon Heavy, with its enormous lifting capacity, could help accelerate the roll-out.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

SpaceX does not talk much about its broadband plans, but that is true of all the companies that have similar proposals.

Some of these firms have already launched pathfinders. Telesat of Canada, for example, launched its Phase 1 LEO satellite in January. This is a prototype for more than 100 follow-on platforms.

Perhaps the most advanced mega-constellation in this field is OneWeb, which will be launching 10 satellites later this year for a network that will eventually comprise at least 600, but which could eventually encompass more than 2,000 spacecraft.

OneWeb is backed by heavyweights in the space industry, such Airbus, Qualcomm, Intelsat, Hughes, and MDA.

The rush to push up these broadband mega-constellations has prompted some concern on the part of those scientists who study space debris.

Computer models have suggested that unless there is a robust strategy to remove old or broken satellites from these networks, the probability of in-orbit collisions will rise dramatically.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external