Atacama's lessons about life on Mars

- Published

The Atacama has been in a hyperarid state for millions of years

Even in the driest places on Earth there is life eking out an existence, it seems.

Scientists have examined the soils in those parts of the Atacama desert that may not see any rains for decades.

Still, the team led from the Technical University of Berlin, Germany, found evidence of microbes that have adapted to the extreme conditions.

These hardy organisms are of interest because they may serve as a template for how life could survive on Mars.

"All the stresses you have in the Atacama, you have on Mars, too - just a little tick more," TU Berlin's Dr Dirk Schulze-Makuch told BBC News.

So, as well as super-aridity that means even higher levels of ultraviolet radiation and soils that are loaded with salts. Dr Schulze-Makuch's team sampled a range of sites in the South American desert - from those places that get a regular wetting from fogs to those where precipitation of any form is extremely rare.

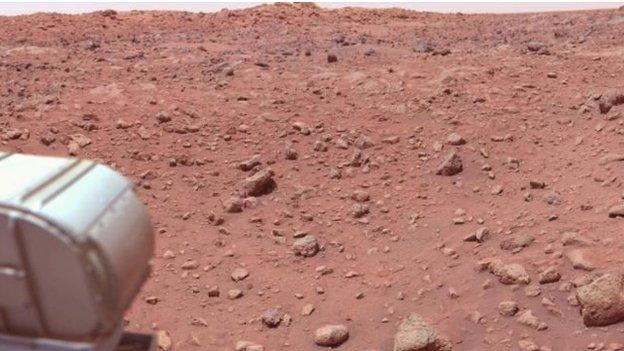

The Atacama's similarities to Mars mean it is used as a location to film sci-fi movies

As luck would have it, the scientists turned up in 2015 just a month after one of the celebrated freak rain events.

Perhaps not surprisingly given the presence of water, the team detected metabolising microbes in the heart of the Atacama. And then, equally unsurprisingly, the researchers saw the level of that activity decline sharply in the following two years as conditions dried out.

"Some have argued that what you're seeing is simply organisms that have blown in on the wind - that what you're seeing is just the remnants of cells and DNA of these organisms as they are dying.

"But what we found from our genomic analysis is that there are organisms in the ground that have adapted to high UV radiation, to high salt concentrations," Dr Schulze-Makuch explained.

In other words, these microbes are indigenous. And when the water comes they become active; and when the water goes, many will obviously die but a good number will go into a dormant state to await the next precipitation event.

Mars wasn't always so dry: Billions of years ago it had a lot of water

This could be how life persists on Mars today - if ever it was there in the first place, said Dr Schulze-Makuch.

"About four billion years ago, there was a lot of water on Mars; you even had oceans. And then it got drier and drier.

"But even nowadays you have these moisture events. You get fog there; you have even nightly snow storms; and there are these 'recurring slope lineae', which are these briny flows near the surface. Water will also form around minerals.

"Think about microbes - for them a little puddle is an ocean. So if they have only just a little bit of water, it may be enough for them."

The team cannot say how long the dormant Atacama species can survive without coming into contact with water, but it could be hundreds or even thousands of years, the scientists think.

Dr Schulze-Makuch's group is about to return to the desert to follow up on their sampling locations.

Their study is published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, external.

Space technology destined for Mars is often trialled in the Atacama

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external