Bloodhound Diary: The sound of speed

- Published

A British team is developing a car that will be capable of reaching 1,000mph (1,610km/h). Powered by a rocket bolted to a Eurofighter-Typhoon jet engine, the vehicle aims to show its potential by going progressively faster, year after year. In 2018, Bloodhound, external wants to run above 500mph. In 2019, the goal is to raise the existing world land speed record (763mph; 1,228km/h) to 800mph. And in 2020, the intention is to exceed 1,000mph. The racing will take place on Hakskeen Pan in Northern Cape, South Africa.

Plans are developing nicely for our forthcoming "Bloodhound 500", external test session later this year.

Bloodhound's chief executive, Richard Noble, has just returned from a hugely busy week of meetings in South Africa.

Richard met with the South African Government, the British High Commission team, a whole list of companies (who all want to help) and a range of national media.

No surprise that everyone is getting excited about Bloodhound going to South Africa this Autumn.

While we're busy planning the event schedule for our test runs (lots of you keep asking for more details; I promise we'll update everyone soon!), there's plenty of research still going on to understand how the car will behave.

One of the key things we are looking at is noise.

How much noise will the car generate? How will this noise affect the structure of the car, the driver (me!) and the watching crowds?

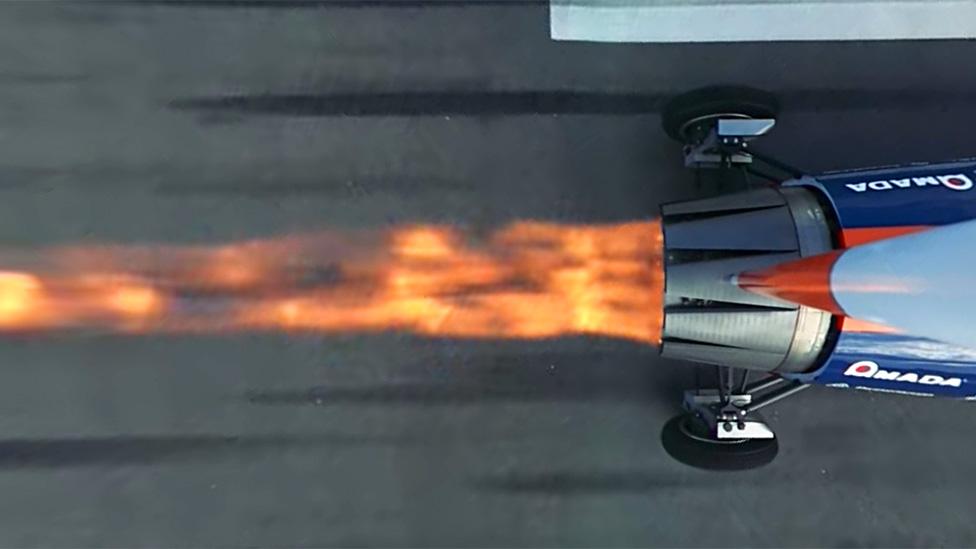

The noise will come from two main sources.

The jet engine and the rocket motor will create a lot (and I mean A LOT) of noise at the back end of the car, with a bit of jet intake jet noise over the cockpit as well.

Lots of noise

At supersonic speeds, I don't have to worry about the jet intake noise anymore, as I'll be travelling faster than the sound the jet engine is making.

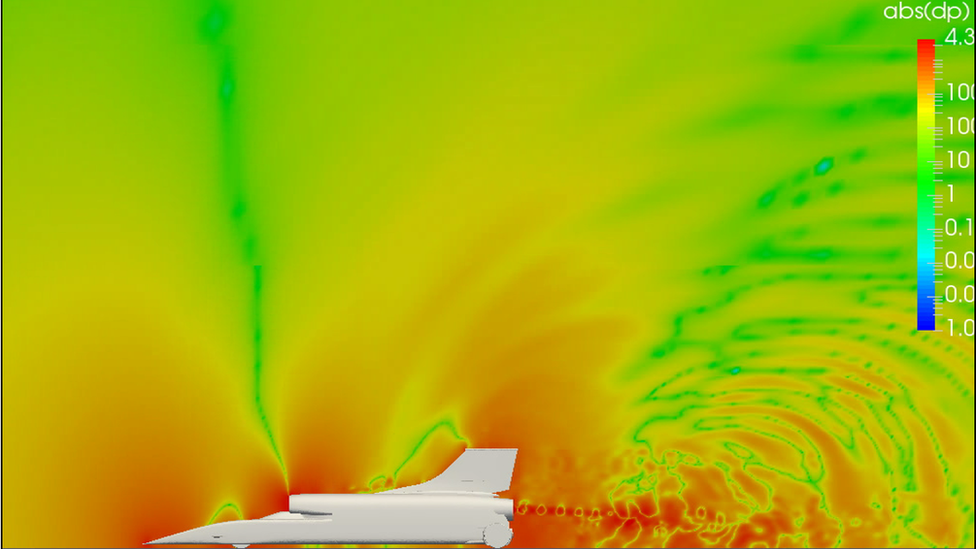

However, at that point, the supersonic shockwaves start to generate some fairly large "acoustic energy effects".

In other words, they will probably create even more noise than the jet intake, so it's going to be noisy whatever speed we're doing.

You may be surprised to hear that I'm not that worried about the noise levels in the cockpit.

During our "slow speed" (200mph) tests at Cornwall Airport Newquay last year, we found that the cockpit was not as noisy as we had first thought.

If we find it's getting too noisy when we go faster (like supersonic fast), then we can fit a lot more sound-proofing.

We've already got a big box of something called "Basotech" (the same sound-absorbing foam that Ariane rockets use), ready to fit in the cockpit if required.

We're not too worried about the effects on the crowd either, as there are some easy solutions.

First, we'll be monitoring the noise levels at the edge of the track, when the car runs.

If it gets too noisy, then we'll simply move the crowd line back further (don't worry if you're coming to see us, it won't be too far and you'll still get a fabulous view!).

In fact, the main problem may come when we get round to timing our final runs, to set a new World Land Speed Record.

At this point we need FIA timekeepers, who traditionally use a few hundred metres of cable to record their timing light signals.

We've already warned them that they are probably going to need wireless timing equipment, as they are likely to be a kilometre of more back from the track.

The real thing we're concerned about is the noise effects on the car.

Back in 1997, when we set the current World Land Speed Record, we saw quite a lot of acoustic damage to the car.

This included cracking of the titanium panels at the rear of the car, due to the shattering noise of the jet engine exhaust.

Really big noise

The supersonic shockwaves also did their fair share of damage.

We had to replace one of the body panels under the car, which was cracked by shockwave vibrations.

Things like rocket motors can produce so much energy that they risk destroying the vehicle (usually a spacecraft) that they are attached to.

For example, the Space Shuttle had to use massive water sprays to damp down the acoustic energy at launch. And I do mean "massive' - they sprayed over one million litres of water on to the launch pad in just over half a minute, to prevent acoustic damage to the payload and crew. That's a lot of water and a lot of noise.

Bloodhound is not going to be using anything the size of the Shuttle main engines, which is just as well, as there's nowhere on the car to keep a million litres of water.

We can't just ignore the problem, though.

Between them, the Rolls-Royce jet engine and the Nammo hybrid rocket will make Bloodhound SSC the loudest (as well as the fastest) car in history.

We need to make sure that all this noise is not going to damage the back end of the car.

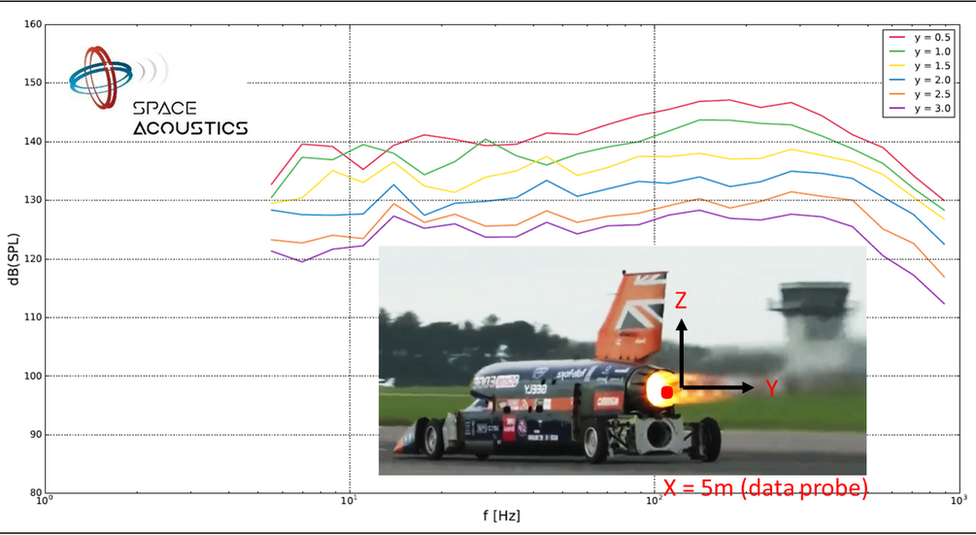

This is where our new best friend Nick Eaton of Space Acoustics comes in.

Nick is developing an "advanced numerical solution to noise from turbulent mixing" for Bloodhound.

In short, that means he's modelling the noise.

His first model is for a speed of Mach 0.8, in other words 80% of the speed of sound, or around 600mph.

That's comfortably above our Bloodhound 500 target for this year of 500+ mph, to give us some worst-case noise figures to look at for this year's testing.

This year's test runs will be with our EJ200 jet engine only, as the rocket development will not be completed until next year.

For the test programme, that makes things simpler, as we can focus on two cases - jet engine at full power (measuring the total noise exposure of the car) and jet engine off (measuring the noise from the airflow only, as the car slows down).

That will give us accurate figures for the airflow noise and, by measuring the difference with power on, for the jet engine noise.

Nick can then use these figures to improve the accuracy of his model (if required), before we fit the rocket and start doing supersonic runs.

How noisy is this going to be?

Before I talk about the expected noise levels, I have to touch on the difficult subject of noise measurement.

Nick's figures are looking at something called the Sound Pressure Level (SPL), which is a measure of the pressure caused by the sound waves.

This is ideal for Bloodhound's requirements, as we want to understand how the sound might affect the structure of the car, so it's the pressure that we're interested in.

Slightly confusingly, the sound pressure is different to the power or energy of the sound wave, for reasons I won't attempt to explain - just take my word for it.

Sound Pressure Levels

The SPL is measured relative to a reference pressure, which is the quietest sound that you can hear.

To make things a bit more complicated, it's measured on a logarithmic scale, in units called decibels, or dB.

The quietest sound your ear can detect is reference pressure at 0 dB(SPL).

On this scale, 20 dB(SPL) is 10 times the sound intensity of 0 dB, and 40 dB(SPL) is 100 times the intensity. Confused? Yes, me too. Let's stick to some simple examples.

If 0 dB(SPL) is the quietest sound you can hear, then the "pain threshold" of sound, where the noise starts to cause you injury, is around 120-130 dB(SPL).

The variation is because the pain threshold is slightly subjective: a really loud (130 dB(SPL)) rock concert may well be "great music" to a 20-year old and "painful noise" to someone over 40….

With 130 dB(SPL) as a "painfully loud" reference (at least for me - I'm over 40), the sound levels around BLOODHOUND may make a bit more sense.

The predicted noise level (SPL) at the cockpit is 135 dB, so it may not be comfortable, but it's nothing to be scared of.

I'll be wearing a full-face helmet and Ultimate Ear moulded earplugs (like you see the F1 drivers using), so I'm well protected against this level of noise.

For a well-protected driver

Of more interest is the prediction for noise at the back on the car, where the SPL figure is 150 dB. This is really quite loud. Unhelpfully, most of the examples of this kind of noise level are things like military jet engines or heavy artillery gunfire.

Unless you work with military jets or heavy artillery, this doesn't mean much.

More exciting is the sort of effects that it has on the human body, which are variously quoted as "chest cavity vibrates", "giddiness" and "choking".

This noise level will damage more than just your hearing.

OK, we'll make sure that we all keep well back.

Question is, what's it going to do to the car itself?

Now that we have this data, our engineering team can start to look at exactly this question.

Better still, we can measure the effects on the car when we start testing it later this year.

If you want to see how we get on, come along and join us, external for our first high-speed test session this autumn in South Africa. We'd love to see you there.

Don't forget to bring your earplugs.

- Published25 December 2017

- Published27 November 2017

- Published26 October 2017

- Published16 October 2017

- Published29 September 2017