Ocean mappers line up for XPRIZE final

- Published

Japan's Kuroshio team brings together technologies from universities, institutes and companies

The $7m XPRIZE competition to find the innovative technologies that can map the world's oceans in rapid time has named its nine finalists.

The teams draw on talents from many nations, with strong interest in the US and Europe, including from the UK.

A technology assessment carried out by the Los Angeles-based XPRIZE Foundation, external late last year whittled the contenders down from an initial pool of 19.

The finalists will now have to demonstrate their tech in 4km of water.

They will be invited to do this in turn in October or November. The precise location has yet to be revealed.

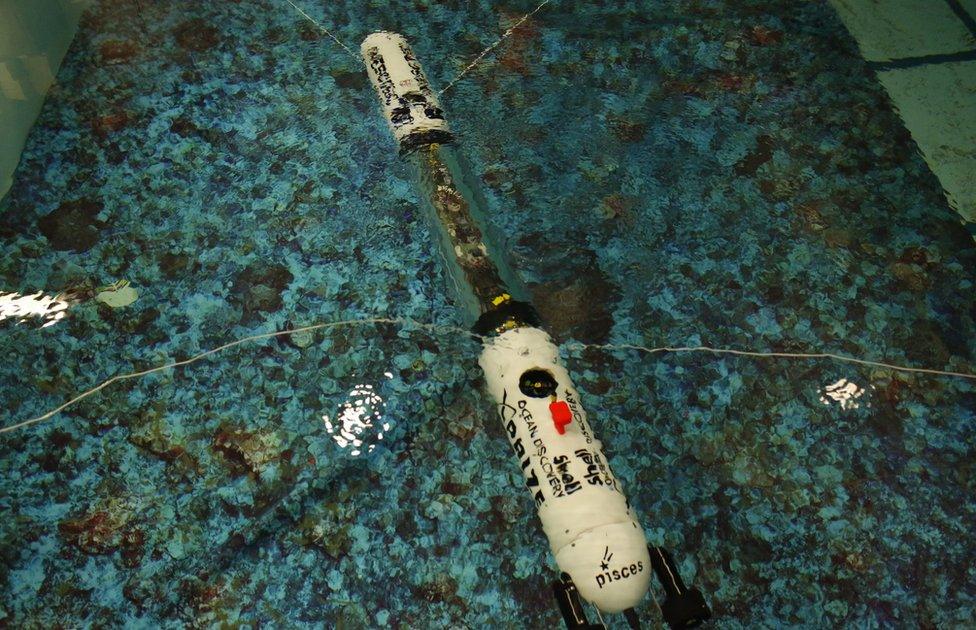

Portugal's Pisces team: XPRIZE judges inspected the teams late last year

"The teams will go to 4,000m depth where they will have 24 hours to map at least 250 sq km at 5m, or higher, horizontal resolution," Dr Jyotika Virmani, prize lead and senior director of Planet and Environment at XPRIZE, told BBC News.

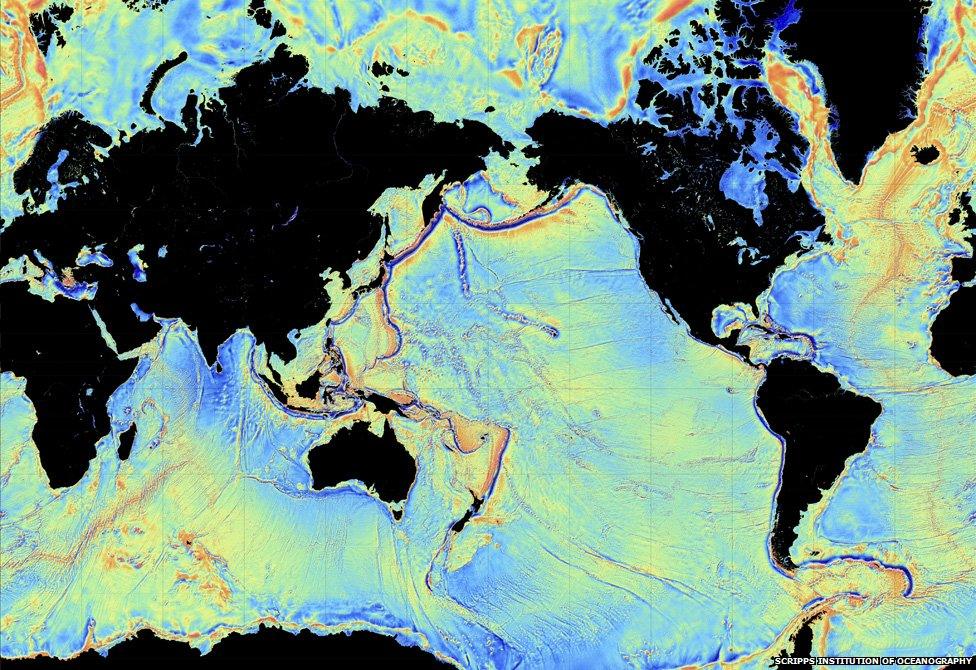

A pressing driver here is the stated international goal, external to have the global ocean entirely mapped to a resolution of at least 100m by 2030.

Currently, our knowledge of the shape of the sea-floor is woeful. Less than 15% of its bathymetry has been measured in a meaningfully accurate way. Most of what we know comes from gravity observations made by satellite and this method cannot see anything smaller than a kilometre in size.

"We will likely award our prize early next year and that's a full decade before 2030. So, there's no doubt in my mind that some of the technologies in the XPRIZE competition will be able to help in that grand quest," Dr Virmani said.

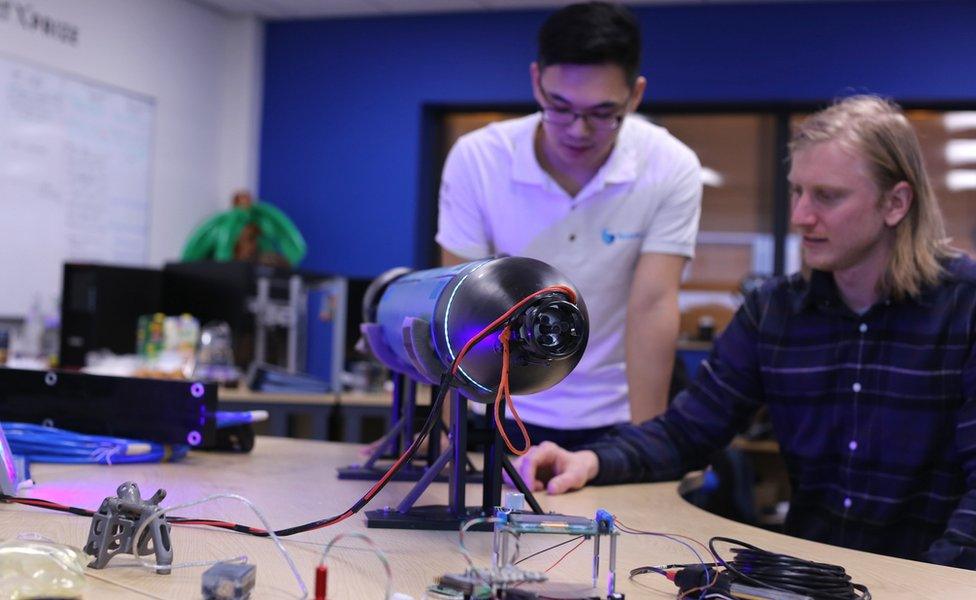

The international Gebco-NF Alumni team uses a UK-built surface vessel to deploy an underwater robot

The finalists have gone for a range of technical solutions that include the use of aerial drones, underwater robotic swarms, lasers and autonomous surface and underwater vehicles.

One of the significant UK contributions to the final is being made by Team Tao. This is a joint venture between Soil Machine Dynamics Ltd (SMD), which makes large subsea vehicles, and the engineering department at Newcastle University.

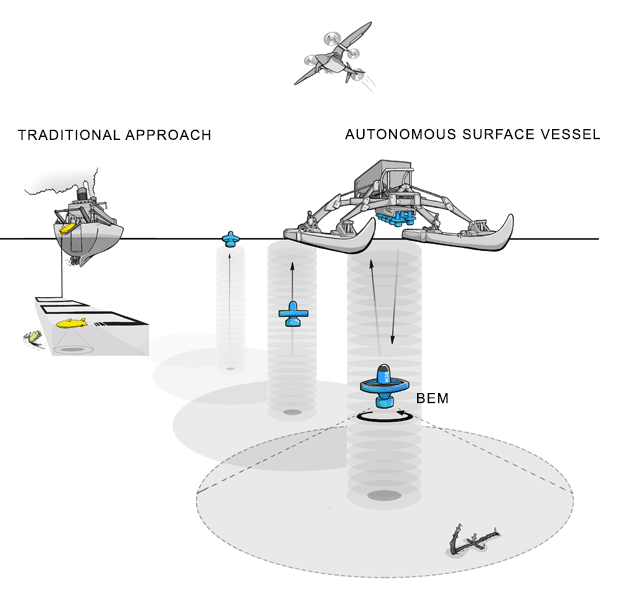

The centrepiece of Team Tao's strategy is a small, torpedo-like robot called a BEM, or a Bathypelagic Excursion Module.

The BEM carries sonar to take depth readings, a camera to snap pictures, and can be equipped with a range of other sensors to acquire oceanographic information as it moves through the water column. Such parameters might include temperature and salinity.

Team Tao will use a swarm of robots to map the sea floor

Team Tao is building its BEMs in-house using largely off-the-shelf materials and components and then qualifying the final designs in a hyperbaric chamber.

The one major feature of its system that is being bought in is a 12m-long autonomous surface vessel. This boat, manufactured in the US, will support up to 24 BEMs, deploying them in batches in the designated mapping zone.

Through a series of dives over the course of a day, Team Tao expects the robot swarm to be able to get depth data for an area covering more than 200 sq km.

"It's amazing to get to the final. We've put so much effort into this," said team leader Dale Wakeham.

"When we first entered we thought it would simply be great to meet and network with people who were doing incredible things, but then when we started working we realised that, actually, we were on to something that could change the industry."

Team Tao's approach to sea-floor mapping

Team Tao's swarm system aims to be 100 times cheaper than traditional ship-borne mappers

The vision is for an autonomous surface vehicle that can carry, deploy and collect a total of 24 robots

BEMs would be released 12 at a time in a dive cycle lasting just over the hour. BEMs spin as they scan

Thrusters enable them to crab across the measurement field. Sub-50cm resolution is being sought

When BEMs are picked up, they dump their data and are put on charge to await the next dive cycle. The surface vessel uploads the data to the cloud

The entire system is expected to cost £1m. It has been designed to fit in a standard shipping container for worldwide use

The latest iteration of the BEM concept is now being produced, with the aim to begin trialling the full system on the water in July.

Whatever the outcome of the XPRIZE competition, SMD and Newcastle University will have nurtured innovative new business.

Prof Nick Wright is the Pro-Vice Chancellor (Innovation and Business) at the northeast university.

"Newcastle University is delighted that our joint entry into the XPRIZE with SMD Ltd - Team Tao - has made the final of this globally prestigious competition," he told BBC News.

"It highlights the outstanding quality of innovative engineering that the team have achieved in a remarkably short timetable and speaks volumes about the remarkable collaboration between the university and this world-leading company."

The other major UK presence in the final will feature in the GEBCO-NF Alumni Team. This international group will deploy an autonomous underwater vehicle from a surface vessel, dubbed USV Maxlimer, built by Hushcraft in Malden in Essex.

The nine Shell Ocean Discovery XPRIZE finalists:

ARGGONAUTS (Karlsruhe, Germany)

Blue Devil Ocean Engineering (Duke University, US)

CFIS (Arnex-sur-Nyon, Switzerland)

GEBCO-NF Alumni (International)

KUROSHIO (Yokosuka, Japan)

PISCES (Portugal)

Team Tao (Newcastle, UK)

Texas A&M Ocean Engineering (College Station, US)

Virginia DEEP-X (Virginia, US)

Most of what we know is the result of low-resolution satellite mapping

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external