Climate change dials down Atlantic Ocean heating system

- Published

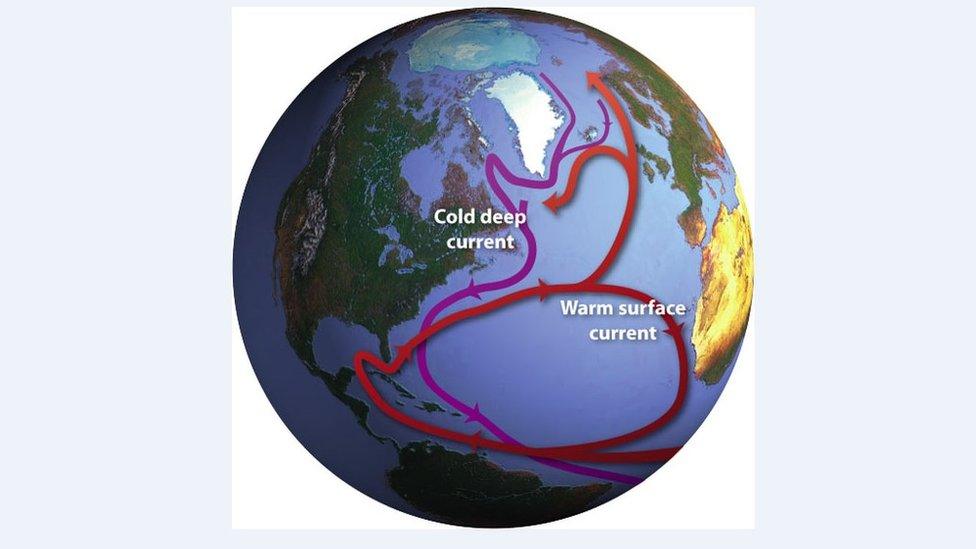

The circulation system plays a "significant role" in regulating the Earth's climate by distributing heat around the globe.

A significant shift in the system of ocean currents that helps keep parts of Europe warm could send temperatures in the UK lower, scientists have found.

They say the Atlantic Ocean circulation system is weaker now than it has been for more than 1,000 years - and has changed significantly in the past 150.

The study, in the journal Nature, says it may be a response to increased melting ice and is likely to continue.

Researchers say that could have an impact on Atlantic ecosystems.

Scientists involved in the Atlas project - the largest study of deep Atlantic ecosystems ever undertaken - say the impact will not be of the order played out in the 2004 Hollywood blockbuster The Day After Tomorrow.

But they say changes to the conveyor-belt-like system - also known as the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (Amoc) - could cool the North Atlantic and north-west Europe and transform some deep-ocean ecosystems.

That could also affect temperature-sensitive species like coral, and even Atlantic cod.

The Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (Amoc) was the basis of the a 2004 science fiction blockbuster

Scientists believe the pattern is a response to fresh water from melting ice sheets being added to surface ocean water, meaning those surface waters "can't get very dense and sink".

"That puts a spanner in this whole system," lead researcher Dr David Thornalley, from University College London, explained.

The concept of this system "shutting down" was featured in The Day After Tomorrow.

"Obviously that was a sensationalised version," said Dr Thornally. "But much of the underlying science was correct, and there would be significant changes to climate it if did undergo a catastrophic collapse - although the film made those effects much more catastrophic, and happening much more quickly - than would actually be the case."

Nonetheless, a change to the system could cool the North Atlantic and north-west Europe and transform some deep-ocean ecosystems.

That is why its measurement has been a key part of the Atlas project.

Scientists say understanding what is happening to Amoc will help them make much more accurate forecasts of our future climate.

Prof Murray Roberts, who co-ordinates the Atlas project at the University of Edinburgh, told BBC News: "The changes we're seeing now in deep Atlantic currents could have massive effects on ocean ecosystems.

"The deep Atlantic contains some of the world's oldest and most spectacular cold-water coral reef and deep-sea sponge grounds.

"These delicate ecosystems rely on ocean currents to supply their food and disperse their offspring. Ocean currents are like highways spreading larvae throughout the ocean and we know these ecosystems have been really sensitive to past changes in the Earth's climate."

Biggest ever deep Atlantic exploration mission launched by UK scientists.

To measure how the system has shifted over long timescales, researchers collected long cores of sediment from the sea floor.

The sediment was laid down by past ocean currents, so the size of the sediment grains in different layers provided a measure of the current's strength over time.

The results were also backed up by another study published in the same issue of Nature, led by researchers from the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research in Germany.

This work looked at climate model data to confirm that sea-surface temperature patterns can be used as an indicator of Amoc's strength and revealing that it has been weakening even more rapidly since 1950 in response to recent global warming.

The scientists want to continue to study patterns in this crucial temperature-regulating system, to understand whether as ice sheets continue to melt, this could drive further slowdown - or even a shutdown of a system that regulates our climate.

- Published17 June 2016