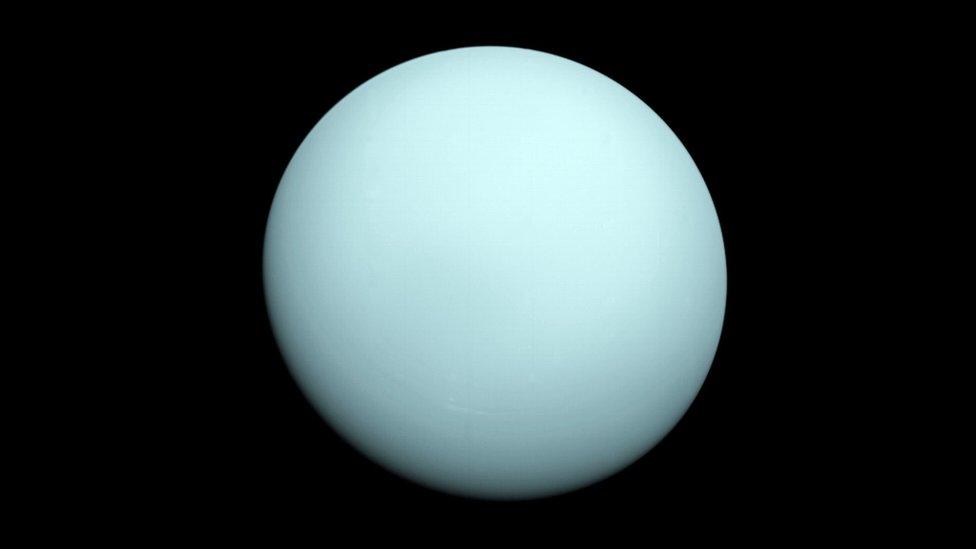

Rotten egg gas around planet Uranus

- Published

The discovery confirms a long-held idea about Uranus' atmosphere

The planet Uranus has clouds made up of hydrogen sulphide, the gas that gives rotten eggs their unpleasant smell.

The possibility of this gas being present in the atmosphere of the seventh planet had long been debated, but has now been confirmed for the first time by observations at a telescope on Hawaii.

The malodorous gas was detected high above the giant planet's cloud tops.

The findings could shed important new light on how the outer planets formed.

A team of researchers have published their results in the journal Nature Astronomy, external.

Despite previous observations by ground telescopes and the Voyager 2 spacecraft, the composition of Uranus' atmosphere had remained unclear.

Scientists have long wondered whether hydrogen sulphide (H₂S) or ammonia (NH₃) dominate the ice giant's cloud deck, but have lacked definitive evidence either way.

The data were obtained with the Near-Infrared Integral Field Spectrometer (NIFS) instrument on the Gemini North telescope on Hawaii's Mauna Kea summit.

The spectroscopic measurements break infrared light from Uranus into its component wavelengths. Bands in the resulting spectrum known as absorption lines, where the gas absorbs infrared light coming from the Sun, allowed the scientists to "fingerprint" components of Uranus' atmosphere.

"Now, thanks to improved hydrogen sulphide absorption-line data and the wonderful Gemini spectra, we have the fingerprint which caught the culprit," said co-author Patrick Irwin, from the University of Oxford.

The detection was made using observations from the Gemini North observatory on Maunakea, Hawaii

The detection of hydrogen sulphide high in Uranus' cloud deck, sets up a contrast with inner gas giant planets such as Jupiter and Saturn. The bulk of Jupiter and Saturn's upper clouds are instead comprised of ammonia ice.

The researchers say these differences in atmospheric composition shed light on questions about the planets' formation and history.

Co-author Dr Leigh Fletcher, from the University of Leicester, said that these differences were probably imprinted early on in the history of these worlds.

He explained that the balance between different gases in the atmospheres of these planets was probably determined by the conditions where they formed in the early Solar System.

According to Dr Fletcher, when a cloud deck forms by condensation, it locks away the cloud-forming gas in a deep internal reservoir, hidden away beneath the levels that we can usually see with our telescopes.

"Only a tiny amount remains above the clouds as a saturated vapour... and this is why it is so challenging to capture the signatures of ammonia and hydrogen sulphide above cloud decks of Uranus," he said.

"The superior capabilities of Gemini finally gave us that lucky break."

Glenn Orton, of Nasa's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, who worked on the study, said: "We've strongly suspected that hydrogen sulphide gas was influencing the millimetre spectrum of Uranus for some time, but we were unable to attribute the absorption needed to it uniquely. Now, that part of the puzzle is falling into place as well."

Dr Irwin explained: "If an unfortunate human were ever to descend through Uranus's clouds, they would be met with very unpleasant and odiferous conditions."

But he added: "Suffocation and exposure in the negative 200 degrees Celsius atmosphere made of mostly hydrogen, helium, and methane would take its toll long before the smell."