Ethics debate as pig brains kept alive without a body

- Published

The scientists used pumps, heaters, and bags of artificial blood to restore circulation to the pig brains

Researchers at Yale University have restored circulation to the brains of decapitated pigs, and kept the organs alive for several hours.

Their aim is to develop a way of studying intact human brains in the lab for medical research.

Although there is no evidence that the animals were aware, there is concern that some degree of consciousness might have remained.

Details of the study were presented at a brain science ethics meeting held at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in Bethesda in Maryland on 28 March.

The research has also been reported on this week in the MIT Technology Review., external

The work, by Prof Nenad Sestan of Yale University, was discussed as part of an NIH investigation of ethical issues arising from neuroscience research in the US.

Prof Sestan explained that he and his team experimented on more than 100 pig brains.

They discovered that he could restore their circulation using a system of pumps, heaters, and bags of artificial blood.

As a result the researchers were reportedly able to keep the cells in the brain alive and capable of normal activity for as long as 36 hours.

Prof Sestan is said to have described the result as "mind-boggling". If this could be repeated with human brains, researchers would be able to use them to test out new treatments for neurological disorders.

But Prof Sestan is among the first to raise potential ethical concerns. These include whether such brains have any consciousness and if so deserve special protection, or whether their technique could or should be used by individuals to extend their lifespans - by transplanting their brains when their bodies wear out.

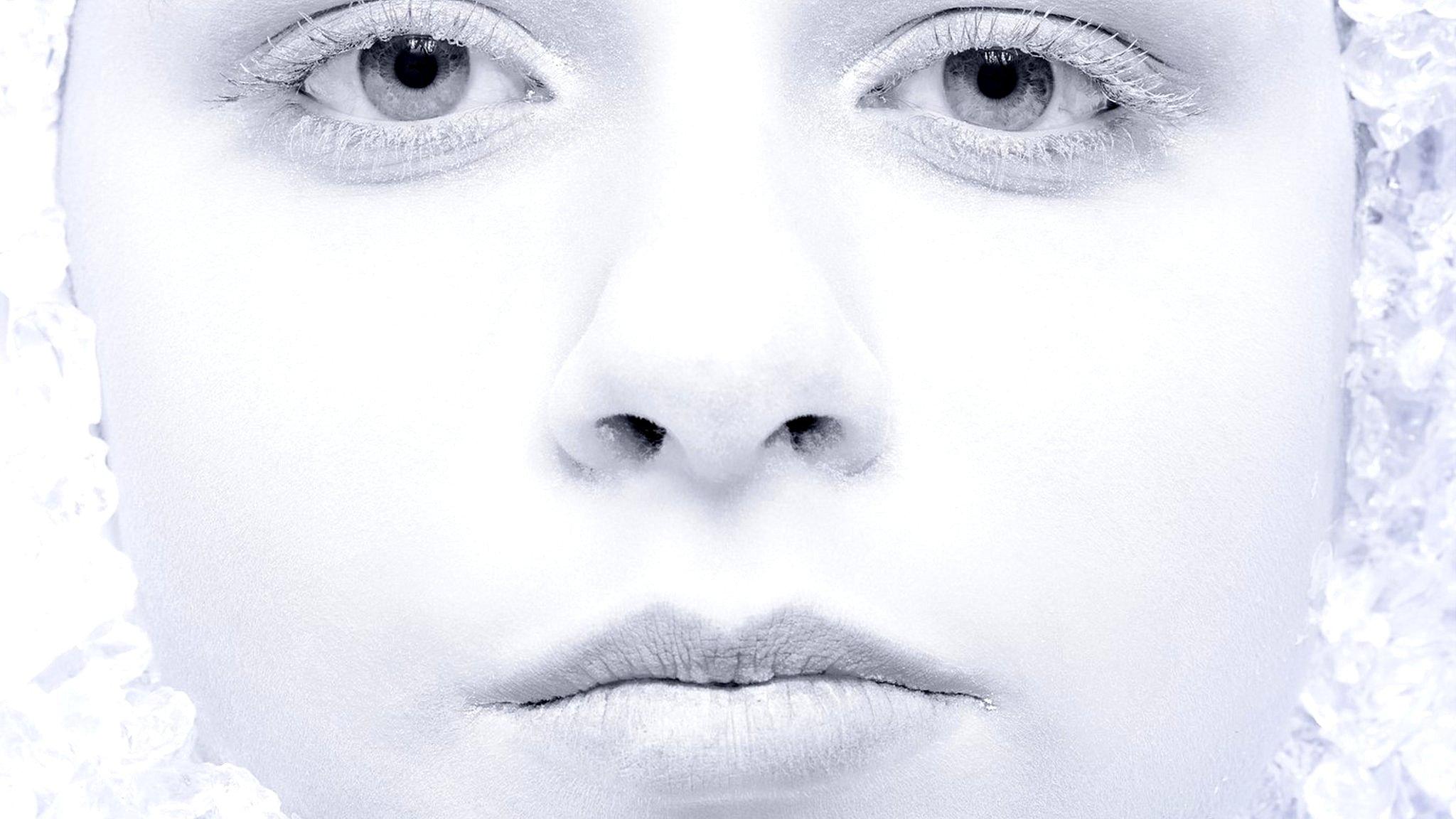

The Yale University researchers recognise that their work raises potential ethical concerns

In a commentary published in the Journal Nature this week, Prof Sestan and 15 other leading US neuroscientists called for clear regulation to guide them in their work, external.

"If researchers could create brain tissue in the laboratory that might appear to have conscious experiences or subjective phenomenal states, would that tissue deserve any of the protections routinely given to human or animal research subjects?", the researchers ask in the commentary.

"This question might seem outlandish. Certainly, today's experimental models are far from having such capabilities. But various models are now being developed to better understand the human brain, including miniaturised, simplified versions of brain tissue grown in a dish from stem cells. And advances keep being made."

The researchers say that ways of measuring consciousness need to be developed and strict limits set for them to be able to continue their work with the public's support.

Prof Colin Blakemore, of the School of Advance Study at the University of London, backs the research team's call for a public debate on the issue.

"The techniques, even to a researcher, sound pretty ghoulish - so it is very, very important that there should be a public discussion about this, and not least because the researchers who have some investment can tell the public why it would be so important to develop such techniques," he told BBC News.

"There is a paradox here, and that is - the better such methods are at maintaining a whole brain, fully functional but without connection to a body, the more useful that would be for research purposes. But the more likely it would also be for the brain to have some sentience and consciousness, which would be deeply worrying".

WATCH: Can you freeze your body for the future?

Prof Blakemore said that he was "very uneasy about the quest for immortality" by those considering preserving their brains until surgery advances, in order to place them in a new body.

"Our planet is already overpopulated. You need space for young people and new ideas, and the notion of desperately clinging on to any mechanism possible for human beings living forever, I find very unsavoury."

- Published14 March 2018

- Published31 January 2018

- Published7 April 2017