Can the UK really go it alone with a new sat-nav scheme?

- Published

- comments

Too high in the night sky to see with the naked eye is a constellation of European satellites at the heart of one of the bitterest disputes in Britain's divorce from the European Union.

Few could have predicted that the repercussions of Brexit would reach into the heavens, but a space venture is now centre stage in a tussle over jobs, technology and security.

"We're looking at a 'lose-lose' for everybody," according to one British industry insider who's spent much of his career working on the European project.

The spacecraft are part of a European scheme known as Galileo,, external a network of satellites which provides highly accurate signals for navigation and timing of a kind on which everyone from taxi drivers to airline pilots to international banks relies.

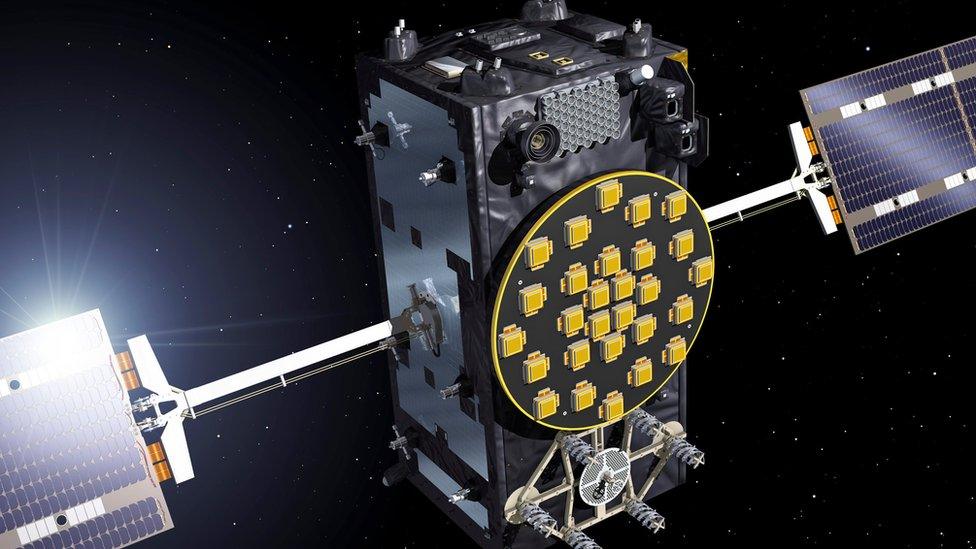

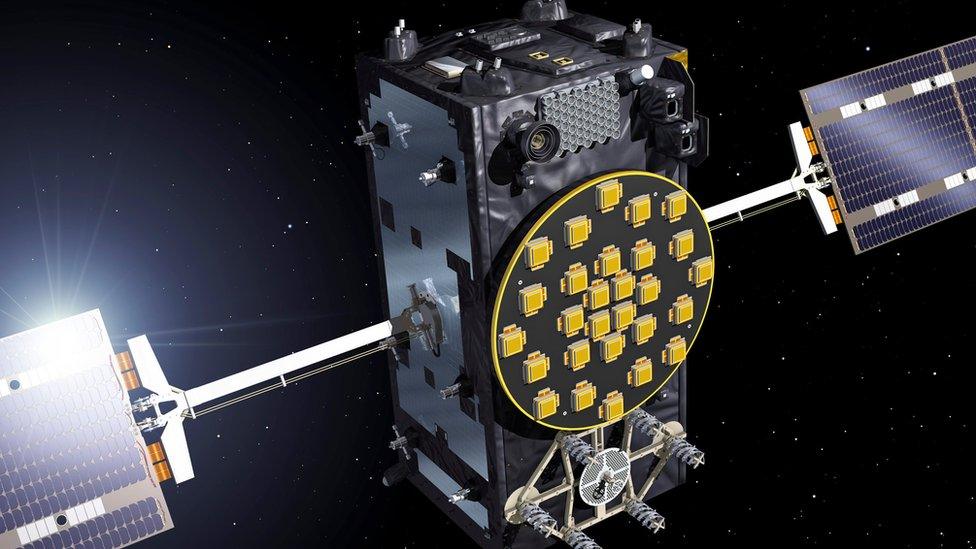

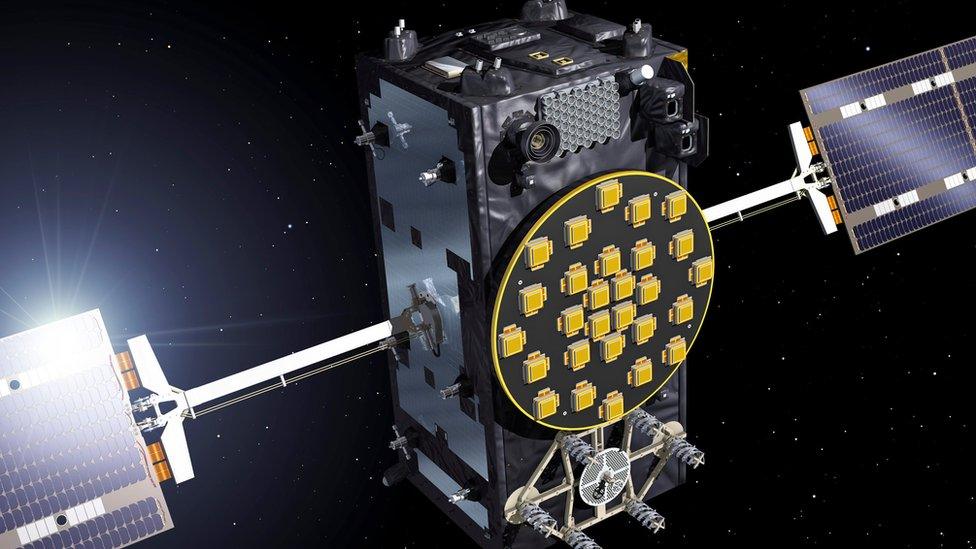

Europe's Galileo system

Artwork: Galileo satellites are now launching on Europe's premier rocket, the Ariane 5

A project of the European Commission and the European Space Agency

24 satellites constitute a full system but it will also have six spares in orbit

22 spacecraft are in orbit today; the 30 figure is likely to be reached in 2021

Original budget was €3bn but will now cost more than three times that

Spacecraft have been launched in batches of two, but now go up four at a time

Will work alongside the US-owned GPS and Russian Glonass systems

Promises eventual real-time positioning down to a metre or less

Galileo was dreamed up as a rival to the US Global Positioning System or GPS, external, which is run by the Pentagon, and which first proved invaluable to military units fighting in the featureless desert in the first Gulf War in 1991.

No longer, it was said, was the most dangerous thing on a battlefield a young officer struggling to read a map.

GPS transformed life not only for armies but also for delivery companies, international shipping and clever firms like TomTom and Garmin that realised that the general public could benefit too. Sat-nav became big business, especially with the advent of the smartphone.

Smartphone apps such as taxi service Uber rely on accurate location information

But with the blessing of reliable navigation came a fear that the Americans, faced with some unforeseen scenario, would switch off the signals, or deny them to the wider world.

And so the idea was born in Brussels that Europe, as an emerging power on the world stage, should have its own system which would not rely on the whim of a general with his finger hovering over a switch in the Pentagon.

Initially, the British military were totally opposed to the idea because they liked GPS, and did not want to appear to be disloyal to the Americans. Britain tried to block progress at every turn and the plan was stalled.

But then a few US voices started to raise concerns about the reliability of GPS - acknowledging that there were areas of the globe that were not well covered, and that the signals could be distorted high in the atmosphere. A single nanosecond of inaccuracy could translate into an error of 30cm on the ground.

So, suddenly, the notion of a second satellite system working in parallel gathered support. The view in Whitehall shifted too, and the project began to take shape.

Nothing moved quickly, however. The costs seemed excessive, and not every EU partner was enthusiastic. Early in the 2000s therefore, the UK government - now worried that Galileo might not happen - commissioned a study into whether Britain could launch its own system.

In the end, the project did gather momentum and the first task was to make sure that the EU "occupied" the radio frequencies allocated to it - the cosmic equivalent of placing a towel on a pool lounger before the crowds arrive.

And in 2005, a satellite called Giove-A - built by the British firm Surrey Satellite Technology Ltd (SSTL) in Guildford - was launched into space, external from Kazakhstan.

I reported from the company's headquarters that day, and there was a powerful sense of pride. It was the beginning of a new era for Europe in space.

Big orders soon followed - and batch by batch SSTL won the contracts to build the "payloads" for every single one of the Galileo satellites. Payloads are the key parts of a spacecraft - containing the highly accurate atomic clocks and the transmitters to send the signals.

Earlier this week, when I again visited the clean rooms of SSTL, staff were preparing to assemble the latest order for 12 more satellites.

There are already 18 of their high-tech creations in orbit, operating a preliminary service, with four more due to be launched later this summer.

And just as the network approaches being fully ready, a vicious exchange over Brexit has broken out.

The initial row was over the most accurate of the Galileo signals, an encrypted one reserved for government agencies such as the emergency services or the military.

It's called the Public Regulated Service (PRS), although "public" in this case means "state" rather than open to anyone.

Access denied

And that is why the European Commission has said that Britain will not get access to it once it leaves the EU next March.

Cue some surprisingly stern words from Chancellor Philip Hammond and Business Secretary Greg Clark, ministers normally seen as keen on close ties to the EU.

And it also provoked a bold threat from Number 10 that Britain was perfectly prepared to launch its own satellite navigation system and London would go it alone. The Sun pictured Theresa May in a spacesuit., external

The argument is that if the EU is serious about having a future security relationship across the Channel, then surely Britain should be allowed to share the PRS. Apart from anything else, the encryption service was partly developed by a firm called CGI, based in Britain.

But the divorce runs deeper than signals. The rules say that companies bidding for future work on Galileo must be led from an EU member state. Already some orders have been lost by British companies.

On Wednesday, Airbus UK managing director Colin Paynter told a Commons committee hearing on Exiting the European Union that EU rules require it to transfer all related work to its factories in France and Germany.

Colin Paynter said Airbus's Galileo work could not continue in Portsmouth

On the horizon is the highly prized "Batch 4" project to design and build satellites that would form the next generation of the system. This kind of work is political gold because it involves highly skilled jobs, and everyone wants them.

High stakes

If British firms are excluded from the bidding, there are plenty on the continent who would like it.

This is the context for the government "Plan B" to launch a British system. Expensive? Anything from £2-5bn. Feasible? Yes, British firms have the skills. As good as Galileo? Possibly not.

SSTL's Sir Martin Sweeting insists the UK must be part of future satellite system development

Sir Martin Sweeting, founder of SSTL, said: "My preference - if I put a UK hat on - is that we negotiate a sensible approach to be able to stay in Galileo, and have full access to the secure elements of it, and maintain both our contribution to the payloads and the important ground segment.

"But if I look at it from a company point of view, we'd be delighted to build a sovereign constellation of navigation satellites. That would be a an incredible boost to our capability."

And the worst option? Sir Martin thinks it would be that the negotiations drag on so that the UK does eventually stay in but also misses the chance to bid for the latest generation of work in the next couple of years.

So, amid these high stakes talks, are there any positives?

Richard Peckham, a veteran of the UK space industry who also worked on Galileo, says that while he and many colleagues voted Remain in the Brexit referendum, "people are now looking further afield beyond Europe and with more ambition".

"It's not all doom and gloom," he told me. "I'd rather stay in, but a British sat-nav would be a fantastic shot in the arm."

- Published9 May 2018

- Published25 April 2018

- Published26 March 2018

- Published21 November 2017

- Published20 June 2017