UK space needs 'bold national plan'

- Published

- comments

Britain has traditionally pushed most of its space money through Esa

The UK needs to beef up its national space programme if it wants to win a bigger slice of the global market.

That is the conclusion of a new policy document that identifies the areas where Britain should concentrate efforts to win more business.

The industry-led Space Growth Partnership (SGP) says there are major opportunities in Earth data, in in-orbit robotics and launch services.

But it says a robust national programme is key to unlocking private investment.

This is an observation that has been made frequently down the years.

Perhaps the best illustration of the issue is the comparison of the proportion of money the British government spends through the European Space Agency (Esa) versus its investments at home.

Currently, the UK puts a third less directly into domestic activity, whereas countries like France and Italy inject a third more than their Esa subscription.

The SGP document calls this a "fundamental weakness" in approach that limits the country's ability to amplify and exploit the benefits it derives from its European endeavours.

A sharper national space programme, based on sustained investment rather than ad-hoc funding, would have the added bonus of pulling in much more private spending, the SGP believes.

"We must... address the fault lines running through our current way of working, chief of which is the absence of a joined up, UK-focused, long-term national programme that allows us to unlock the full potential of our industrial-academic powerbase," the new document, titled "Prosperity From Space", external, says.

The UK space sector has been a tremendous success story.

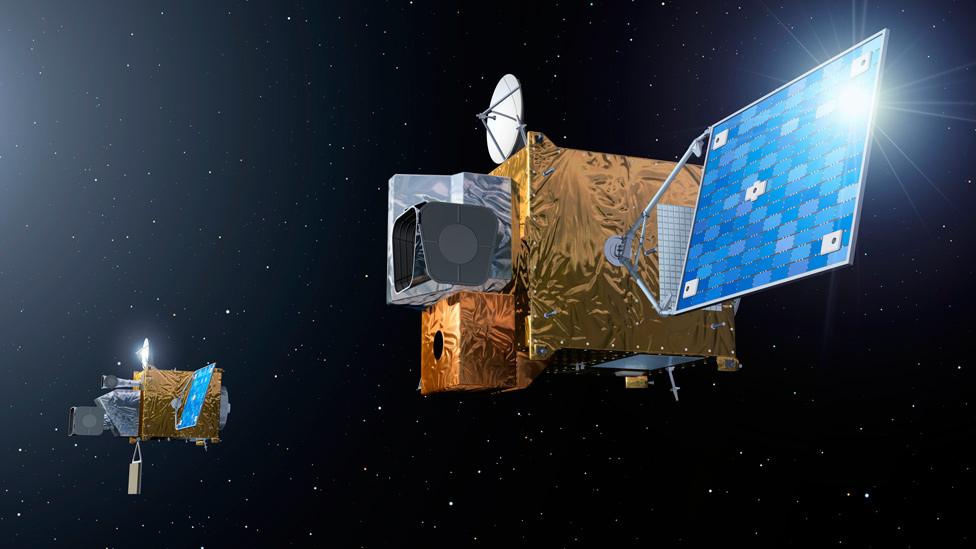

A UK-developed satellite now makes movies of Earth from orbit

Growth since the turn of the century has been five times that of the wider economy.

Front-line activity is now worth some £14bn to the country annually, with nearly 40% of revenues coming from exports. But with competition increasing all the time, the SGP document says the national industry cannot sit back on its heels.

It identifies areas where Britain can push on to achieve the stated goal of capturing 10% of global business (the share currently is 6.5%). These include:

Earth information: There is a forecast £20bn market in services that exploit images and other data from space, including the timing and positioning information transmitted by satellites.

Connected services: Linking everyone and everything through next-generation communications networks, including those operated from space. This is a forecast £40bn market.

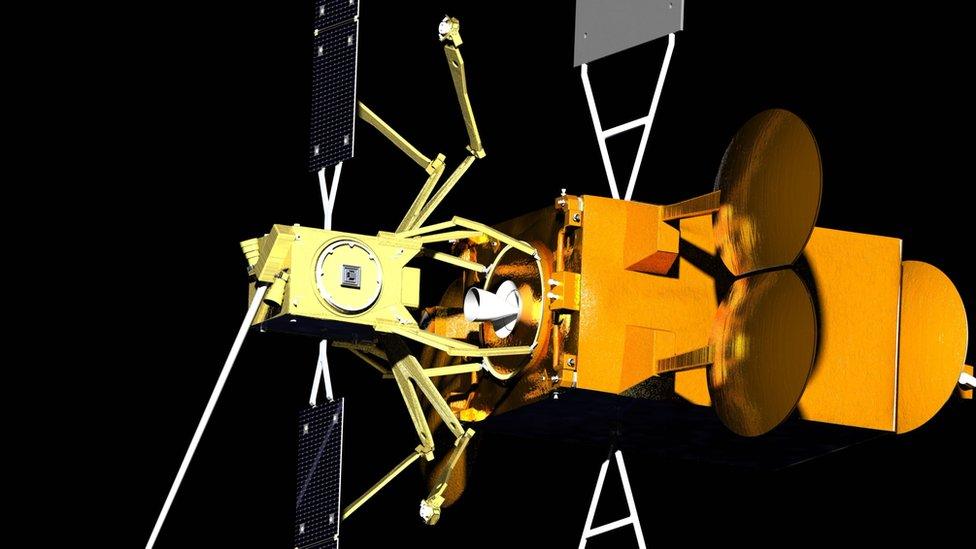

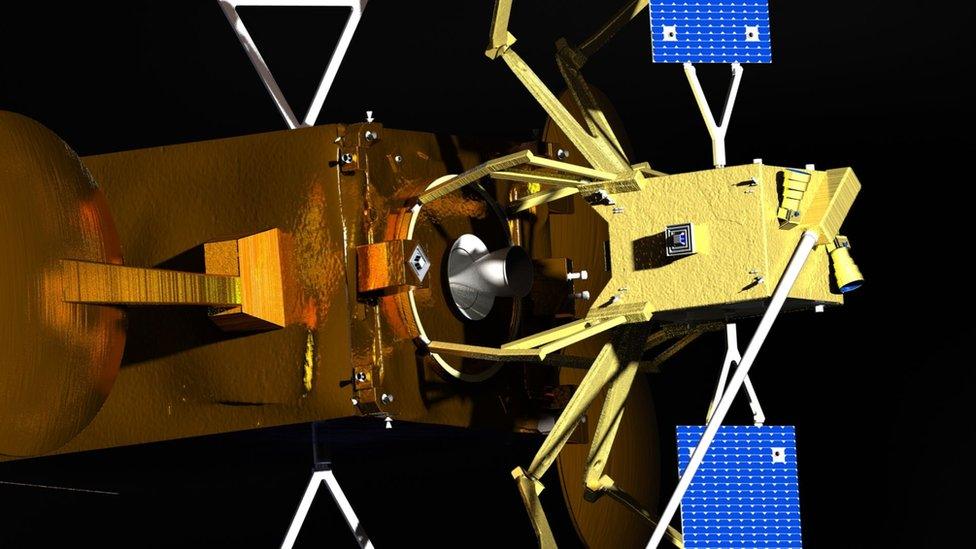

In-space robotics: With huge numbers of new satellites about to go into orbit, there ought to be significant opportunities for businesses able to service operational spacecraft.

Low-cost access: The UK could attract more business if it offers end-to-end services - from the manufacture of satellites to their launch. Spaceport facilities are therefore essential.

Successive governments have bought into a Space Innovation and Growth Strategy first set out in 2010, external. This has led directly to the establishment of a space agency, and the space hub and Catapult applications centre based in Harwell in Oxfordshire. Esa, too, has joined this wave by moving its telecoms research efforts to Harwell.

Artwork: Servicing satellites (yellow) could dock with and service ageing satellites (orange)

The present government has continued the course, and just last year announced a £99m investment in a national satellite test facility, again at Harwell. But the SGP document says ministers can do more, and one of the easiest ways to cement support would be through "smart procurement" - making sure government departments are buying services from British space companies, even becoming "anchor tenants" for some of those services.

The big elephant in the room is Brexit, of course.

With so much investment down the years put through Esa, the UK has inevitably become embedded in the European space ecosystem.

The agency has become the technical agent for the EU, with Brussels now the single largest source of funding for Esa's activities.

Dropping out of the EU's Galileo satellite-navigation programme and its Copernicus-Sentinel Earth observation project would therefore represent a significant bump in the road for the UK space sector.

Graham Peters, the chair of trade group UKSpace, external, calls Brexit a "headwind".

"Not being in the EU space programmes would be a set-back for UK space companies, but it would not be a fatal blow," he told BBC News.

"We would like to stay in those programmes and the government has indicated that this is its intention. So, hopefully both sides can come to some sort of agreement in the negotiations.

"But it's all about confidence - confidence in investing in the sector. And that's why a national space programme is so important. A programme that is sustained would boost confidence and signal to everyone that the British government means business."

The Harwell campus just outside Oxford is a major hub for UK activity

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published10 May 2018

- Published26 April 2018

- Published16 April 2018

- Published12 March 2018

- Published7 December 2017

- Published11 July 2017