'Shocking' human impact reported on world's protected areas

- Published

- comments

Despite more and more land being "protected", biodiversity is still in decline

One third of the world's protected lands are being degraded by human activities and are not fit for purpose, according to a new study.

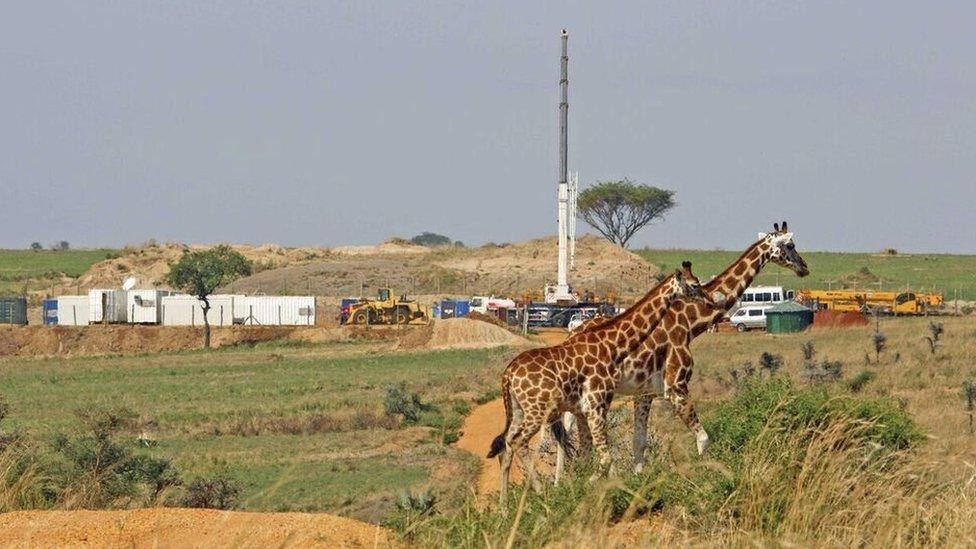

Six million sq km of forests, parks and conservation areas are under "intense human pressure" from mining, logging and farming.

Countries rich and poor, are quick to designate protected areas but fail to follow up with funding and enforcement.

This is why biodiversity is still in catastrophic decline, the authors say.

Global efforts to care for our natural heritage by creating protected zones have, in general, been a huge conservation success story.

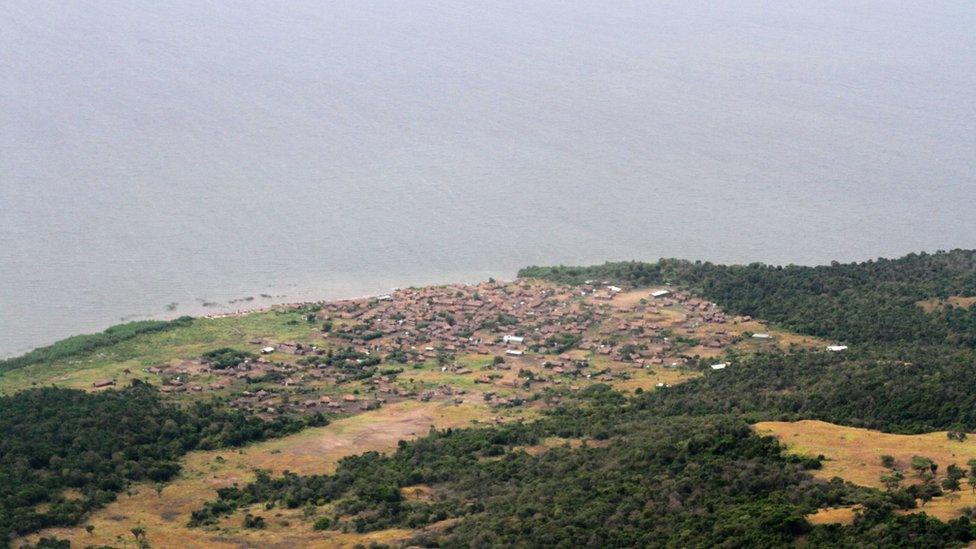

An illegal fishing village located in Virunga national park

Since the Convention on Biological Diversity was ratified in 1992, the areas under protection have doubled in size and now amount to almost 15% of the lands and 8% of the oceans.

But researchers now say that many of these protected areas are in reality "paper parks", where activities, such as building roads, installing power lines, even building cities, continue without restrictions.

"What we have shown is that six million sq km have this level of human influence that is harmful to the species they are trying to protect," the study's senior author, Prof James Watson from the University of Queensland and the Wildlife Conservation Society, told the BBC's Science in Action programme.

"It is not passive, it's not agnostic; it is harmful and that is quite shocking."

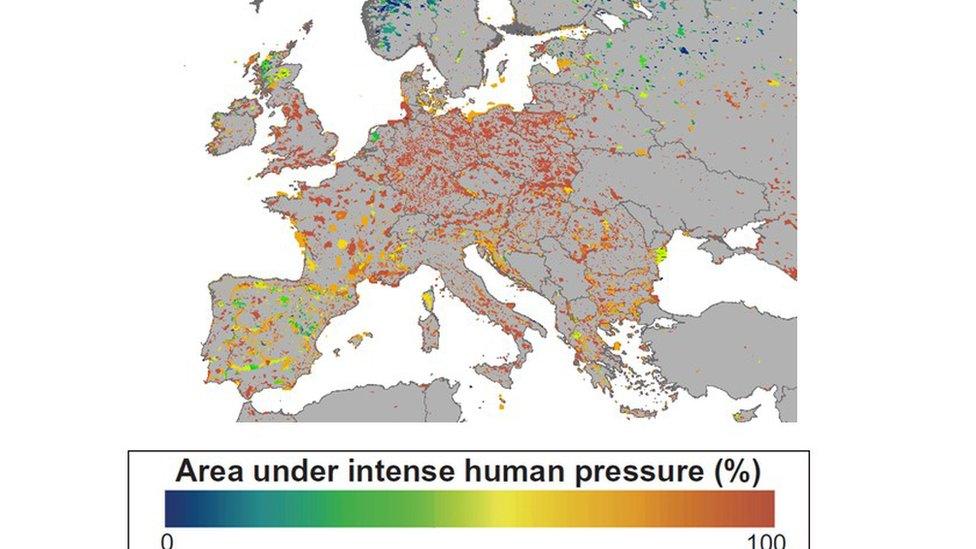

A graphic from the study showing the human impact on European protected areas

"What was scary was that the patterns were consistent everywhere. No nation was behaving very well. All nations were allowing heavy industry inside their protected areas, including very rich nations.

"That's probably the saddest part of our study - that nations like Australia and the US, which have the resources and have this incredible biodiversity to protect, are not safeguarding those protected areas.

"Many areas in Australia have mining in them; they have significant agriculture like grazing; you see logging in the special sites that are meant to be preserved."

The researchers looked at global "human pressure" maps to analyse activities across almost 50,000 protected area. These one km resolution maps were able to show not just mining, farming and logging but the development of roads, power lines and night-time lights - all elements that put pressure on species.

Almost 33% of the protected areas showed the impact of intense human pressure, especially in heavily populated areas of Asia, Europe and Africa.

Niassa national reserve in Mozambique

Only 10% of the areas analysed were completely free of human impacts, and these were lands in the high latitudes of Russia and Canada.

Countries are their own worst enemies, says Prof Watson. Most of the world has signed the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), which commits countries to conservation of species, but also encourages them to report on the quantity and not the quality of their efforts.

"The Convention on Biological Diversity has very little leadership, said Prof Watson. "There is no-one setting the bar, holding the standard of what a nation should do. So, science like this report holds nations to account and maybe embarrasses them to take some leadership because right now no nation is showing that leadership.

"When it comes to their natural heritage, we are running out of time; the extinction crisis is on. Thirty percent of species will go extinct in the next 50 years if we don't safeguard nature properly."

The authors say that there are some positive lessons to be learned. Well funded, well-managed protection areas were extremely effective in halting threats to species, they wrote.

They study is published, external in the journal Science.