Giant canyons discovered in Antarctica

- Published

Kate Winter: "Radar gives us effectively an X-ray of the ice sheet"

Scientists have discovered three vast canyons in one of the last places to be explored on Earth - under the ice at the South Pole.

The deep troughs run for hundreds of kilometres, cutting through tall mountains - none of which are visible at the snowy surface of the continent.

Dr Kate Winter from Northumbria University, UK, and colleagues found the hidden features with radar.

Her team says the canyons play a key role in controlling the flow of ice.

And if Antarctica thins in a warming climate, as scientists suspect it will, then these channels could accelerate mass towards the ocean, further raising sea-levels.

"These troughs channelise ice from the centre of the continent, taking it towards the coast," explained Dr Winter.

"Therefore, if climate conditions change in Antarctica, we might expect the ice in these troughs to flow a lot faster towards the sea. That makes them really important, and we simply didn't know they existed before now," she told BBC News.

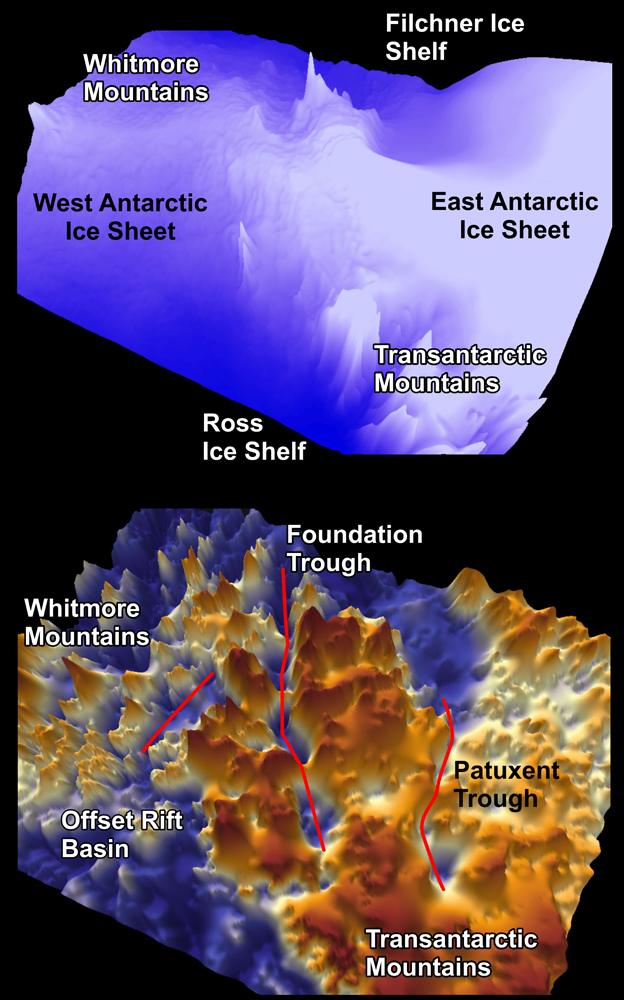

The canyons and mountains are hidden below hundreds of metres of ice

The biggest of the canyons is called Foundation Trough. It is over 350km long and 35km wide.

To put that on a more recognisable scale - think of a deeply incised valley running between London and Manchester.

The two other troughs are equally vast. The Patuxent Trough is more than 300km long and over 15km wide, while the Offset Rift Basin is 150km long and 30km wide. And all of this relief is buried under many hundreds of metres of ice.

To get to the floor of Foundation Trough, for example, you would need to drill through over 2km of ice cover.

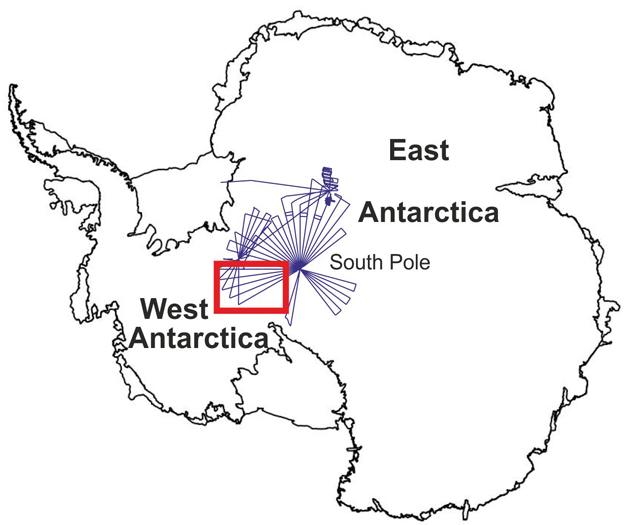

Airborne instruments were flown out from the South Pole, including over the area (red rectangle) where the troughs are sited

The three troughs together lie under and cross the so-called "ice divide" - the high ice ridge that runs from the South Pole out towards the coast of West Antarctica.

This divide can be thought of as a kind of watershed. Ice flows away on either side, through the channels - towards the Weddell Sea in the east and the Ross Sea in the west.

Computer modellers will now take the new information to try to simulate what it means for future warming scenarios.

One important implication is that these canyons and their surrounding mountains will likely act as a brake on any ice which might attempt to flow from the east of the continent, through the Transantarctic mountains, to the west.

"People had called this area a bottleneck," said team-member Dr Tom Jordan from the British Antarctic Survey (BAS).

"The thought was that if the West Antarctic Ice Sheet were to collapse then ice could flood out from the east. But the mountains we've found effectively put a plug in that bottleneck."

It was thought that a gap in the Transantarctic Mountains could provide a route for ice to escape from the east of the continent to the west

The new study, published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters, external, represents the first result to come out of the PolarGAP project, external.

This was funded in large part by the European Space Agency (Esa), which wanted to collect measurements over an area of planet that its satellites cannot see (spacecraft generally only fly up to about 83 degrees in latitude).

The only way to fill this "data hole" is to fly sensors on planes instead.

The insights for Dr Winter's paper come from an airborne ice-penetrating radar. This will describe the layers and total thickness of the ice sheet. It will also map the shape of the basement rock.

"Remarkably, the South Pole region is one of the least understood frontiers in the whole of Antarctica," said PolarGAP's principal investigator, Dr Fausto Ferraccioli from BAS.

"Our new aerogeophysical data will... enable new research into the geological processes that created the mountains and basins before the Antarctic ice sheet itself was born."

It is possible the troughs detected under today's ice sheet were dug out during a previous glacial period when the ice over the continent was configured in a very different way.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external