Dinosaur dandruff reveals first evidence of skin shedding

- Published

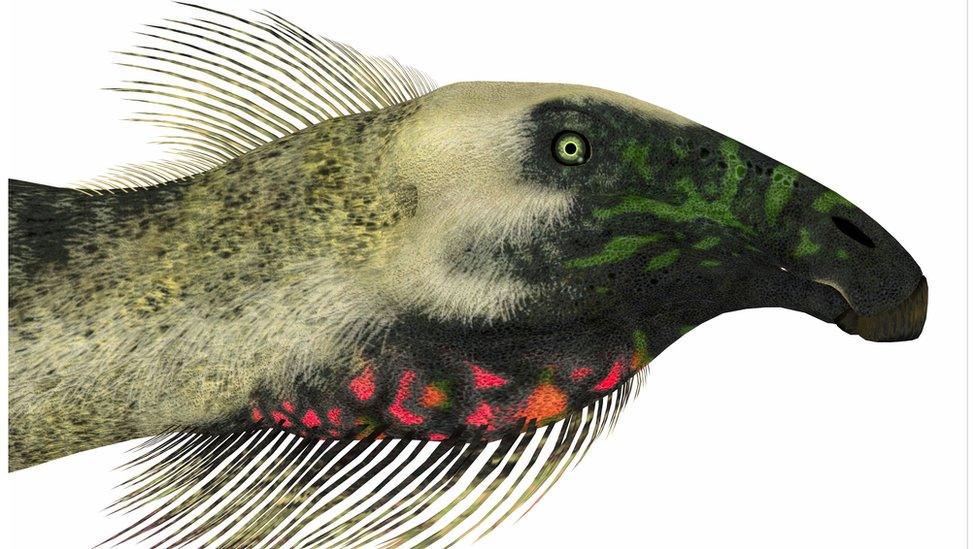

An artist's impression of a microraptor in flight

An analysis of fossilised dandruff fragments has given scientists their first evidence of how dinosaurs and early birds shed their skin.

Found among the plumage of these ancient creatures, the 125-million-year-old flakes are almost identical to those found in modern birds.

It shows that these dinosaurs shed their skins in small pieces, and not all at once like many modern reptiles.

It's more evidence that early birds had limited flying skills, the authors say.

The researchers travelled to China in 2012 to study fossils of feathered dinosaurs from the Cretaceous era. This was the first time that these specimens were subject to electron microscopy and chemical analysis. The results surprised the science team.

The early bird Confuciusornis shed their skin in flaky fragments scientists have learned

"We were originally interested in studying the feathers, and when we were looking at the feathers we kept finding these little white blobs, the stuff was everywhere, it was in between all the feathers," lead author Dr Maria McNamara from University College Cork told BBC News.

"We started wondering if it was a biological feature like fragments of shells, or reptile skin, but it's not consistent with any of those things, the only option left was that it was fragments of the skin that were preserved, and it's identical in structure to the outer part of the skin in modern birds, what we would call dandruff."

The researchers were seeing tough cells called corneocytes, which were filled with twisting spirals of keratin fibres - almost identical to those found in modern birds, and also in human dandruff.

The research team looked at the preserved plumage of a Microraptor, a Beipiaosaurus, and a Sinornithosaurus dinosaur as well as an early bird in the shape of Confuciusornis.

The study suggests that this dandruff evolved sometime in the Middle Jurassic period, when, according to the scientists, there was a burst of evolution in feathered dinosaurs.

The Beipiaosaurus was one of the feathered dinosaurs studied

The authors believe that the dandruff evolved in response to the presence of feathers. These flaky fragments also tell them something important about the way these animals shed their skins.

Co-author Professor Mike Benton, from the University of Bristol, said: "It's unusual to be able to study the skin of a dinosaur, and the fact this is dandruff proves the dinosaur was not shedding its whole skin like a modern lizard or snake but losing skin fragments from between its feathers."

The new study also adds to the body of evidence that these ancient feathered creatures were very different in one key aspect - flying. The researchers say that modern birds have very fatty dandruff cells because this helps them shed heat when they are flying. The older creatures weren't able to fly at all or were only able to get off the ground for short periods.

"In these fossil birds, their cells are packed full of keratin and there's no evidence they had any fats in these cells at all," said Dr McNamara.

"So that suggests they had lower body temperatures than modern birds, almost like a transitional metabolism between a cold blooded reptile and a warm blooded bird."

The study has been published, external in the journal, Nature Communications.