Bloodhound Diary: Braking with confidence

- Published

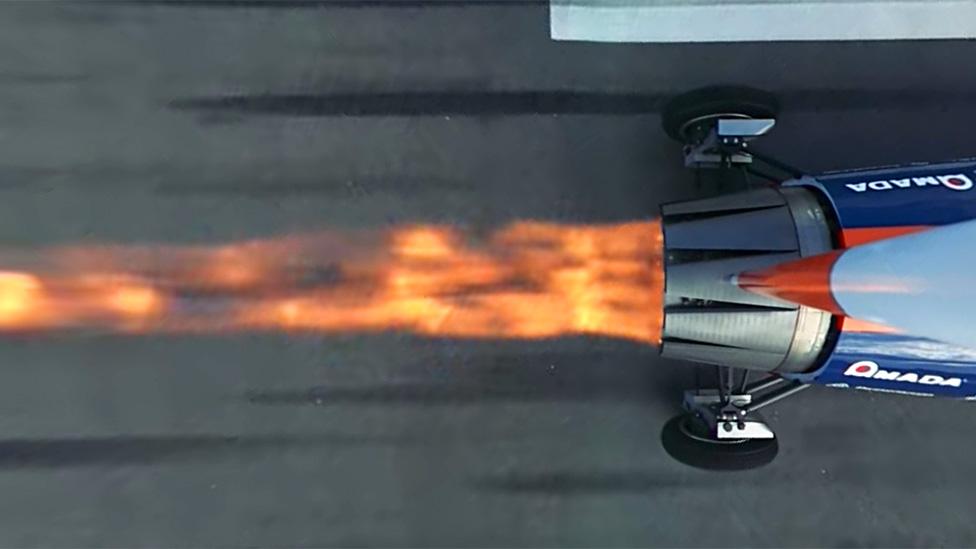

A British team is developing a car that will be capable of reaching 1,000mph (1,610km/h). Powered by a rocket bolted to a Eurofighter-Typhoon jet engine, the vehicle aims to show its potential by going progressively faster, year after year. In mid-2019, Bloodhound, external wants to run above 500mph. In late 2019, the goal is to raise the existing world land speed record (763mph; 1,228km/h) to 800mph. And in 2020, the intention is to exceed 1,000mph. The racing will take place on Hakskeen Pan in Northern Cape, South Africa.

Some disappointing news and some good news over the past few weeks.

The disappointment is that we won't be getting to South Africa this year.

The good news is that after nearly two years of discussions, we've just secured a formal endorsement from a key supporter - more to follow when they let us announce it!

We are still putting the funding together for our record attempts and (as I mentioned last month, external) we have recently lost a couple of key suppliers.

We still haven't sourced replacements for the parts and, with time running out, we've finally had to accept a delay.

We have rescheduled "Bloodhound 500, external" for the second quarter of next year, rather than go late this year.

While it's a little frustrating to have to wait for another nine months, it's a slightly cheaper way of doing the test runs, as it reduces the time (and set up costs) between Bloodhound 500 and the supersonic record runs late next year.

The delay also gives us more time to prepare the car and, from my point of view as the driver, that's a good thing.

New panels in place

With more time to get the car ready, we are now aiming to build a slightly different vehicle for next year's runs.

Instead of a 500+ mph jet car for this year, which we would then upgrade to a jet-plus-rocket supersonic system for next year, we are already starting to prepare the supersonic car.

Bloodhound 500 will be our 500+ mph jet-only test session next spring with this vehicle, then we'll simply "plug in" the rocket and target a new World Land Speed Record in the autumn.

Our rocket team is going to hate me for saying "simply plug in the rocket" - yes, it really is rocket science and no, it's not simple - but you know what I mean.

The "slow-speed" bodywork we fitted for the 200mph test runs last year is now being modified for high speeds.

The Bloodhound build team has been hard at work adding the composite body panels to the rear sub assembly.

They've had to drill almost 100 holes, by hand, with millimetre accuracy to seat the "top hats".

Spreading the load

Top hats are inserts that spread the load from each fixing point into the composite panels.

They are cylindrical in shape with a circular flange at one end - in other words, shaped just like a top hat.

Given the huge acoustic loads and aerodynamic buffeting that the rear bodywork will suffer, these little load-spreading devices are an essential part of keeping the back of the car in one piece.

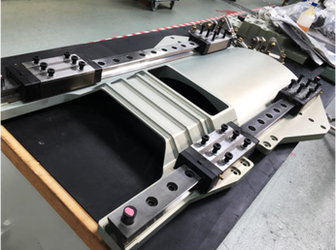

The build team is also test-fitting the airbrake mechanism, with the intent to get it working for our runs next year.

Looking at the performance figures, the Bloodhound 500 test runs will be a great chance to test the braking aids (chutes and airbrakes), as the car can be stopped from 500+ mph even if we have a problem with one of them.

Once we fit the rocket and start aiming for supersonic speeds, we are going to need help to stop the car, so these will be important tests.

We are fitting both brake 'chutes and airbrakes to the car to give us multiple options for stopping.

It's all very well being able to go fast, but we need to make sure we can stop every single time. So, using 'chutes and airbrakes is (at least as far as I'm concerned) the best solution.

With Bloodhound 500 now scheduled for next year, it will allow us to test both systems at the same time, giving us more experience (and confidence) with the braking aids before we start going really fast.

Braking with confidence

When we start running at high speeds we are going to learn a huge amount about the car and its performance.

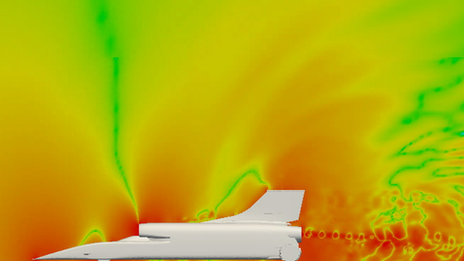

The biggest and most exciting area of research is, of course, the aerodynamics.

While we've got the very best of cutting-edge computer science behind us, this is still a relatively "new" area of technology that Bloodhound's data will help to develop.

The car is running with almost 200 aerodynamic pressure sensors on it for exactly this reason.

Swansea University is already using Bloodhound for both research and for teaching its most advanced students.

Some of the flow visualisations they are producing are simply stunning, but it does leave me with one concern.

The simulations clearly show a huge supersonic shockwave sitting over the cockpit, which is exactly what's supposed to happen, in order to slow down the supersonic airflow to below Mach 1 (the speed of sound) before it gets to the jet engine.

That's all well and good - but just how noisy is it going to be, exactly, sitting directly underneath this screaming banshee of angry supersonic airflow?

The aerodynamics is just one area where Bloodhound's data is going to provide key information to attack our ultimate target of 1,000mph.

Look closely, it's there somewhere

Our latest Cisco BHTV gives a good summary of where we've been using data so far, and where we will be using it over the next couple of years.

Of course, we're also planning to stream the data live to a global audience, so if you want a preview of what we're planning, or if you've ever wondered what a "digital twin" is, then have a look at the video, external.

Finally, some good news about our track.

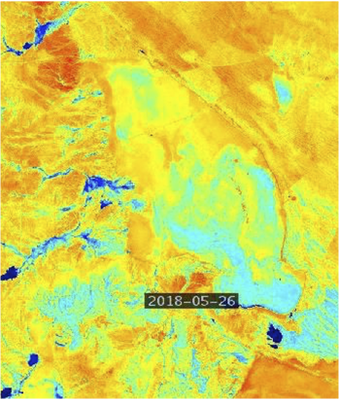

After last month's extensive flooding, a recent satellite photo shows that the surface has already dried out.

The picture shows the "moisture index" from Sentinel-2.

While this carefully selected set of frequency bands looks like a piece of abstract art, it does show the outline of the desert if you look closely.

The picture shows surface water as a dark blue colour, so it's obvious that Hakskeen Pan is pretty much dry.

Now, we just need to get a supersonic car on to it...

- Published5 March 2018

- Published25 December 2017

- Published27 November 2017

- Published26 October 2017

- Published16 October 2017