How hats were placed atop the Easter Island statues

- Published

Terry Hunt: "Some of the most accomplished achievements of the ancient world"

The famous statues of Rapa Nui, or Easter Island, are best known for their deep-set eyes and long ears.

They also sport impressive multi-tonne hats made from a different rock type.

Quite how these pukao, as they are known, were transported and placed atop the statues has long been a puzzle.

But now American archaeologists believe they have a clearer understanding. The giant hats were moved with minimal effort and resources using a ramp and rope technique, they say.

"The fact that they successfully assembled these monuments is a clear signal of the engineering prowess of the prehistoric Rapanui people," said Sean Hixon, lead author and graduate student in anthropology, at Penn State.

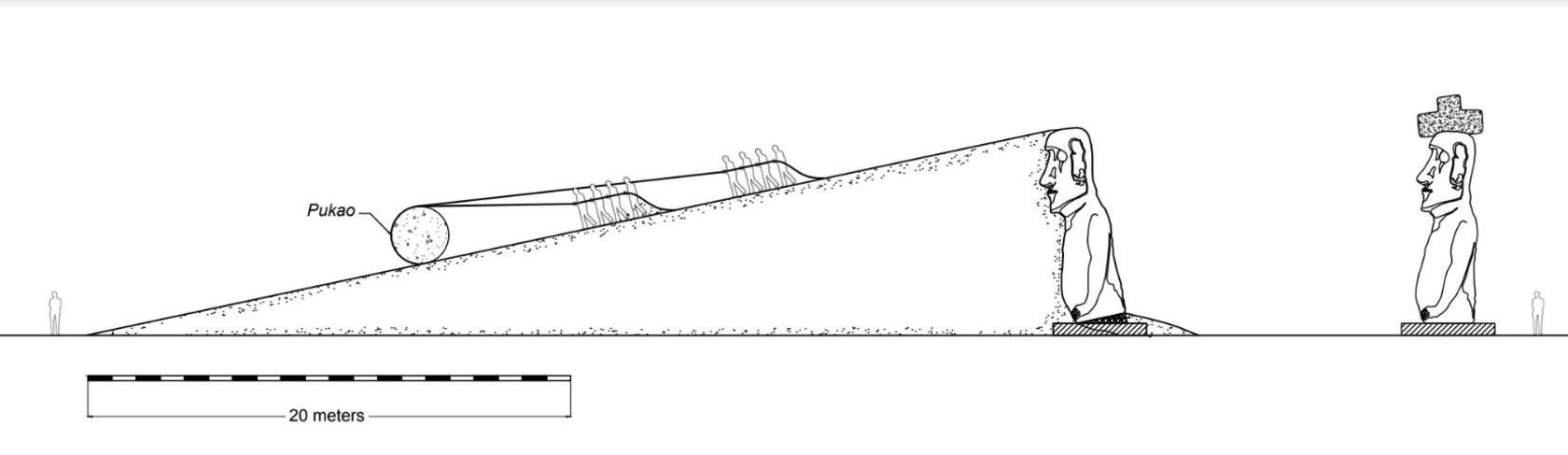

The pukao emplacement process

The researchers' investigations indicate the pukao were rolled across miles of rugged terrain and earthen ramps to reach the top of the ancestor heads, called Moai. The largest of these colossal red hats has a diameter of over 2m and weighs nearly 11 tonnes.

The researchers motion-mapped overlapping digital photographs to capture surface details of each pukao. By applying filters to their models, they began to identify clues that are shared among pukao which show the marks of wear and tear in how they were moved.

The team's findings, published in the Journal of Archaeological Science, external, argue that similar notches, grooves and indentations suggest the Rapanui people built ramps in front of forward-leaning Moai. They then rolled the hats till they reached the top, before finally tipping the Moai upright.

Islanders are likely to have wrapped the pukao with ropes to roll and tip them. This "parbuckling" method, often used today to right capsized ships, would have made moving the stones physically feasible and required smaller groups of individuals to be involved.

"Even in the case of the most massive pukao that was brought to the top of the tallest statue, 10 people likely could have rolled it up a ramp with reasonable dimensions," Mr Hixon explained.

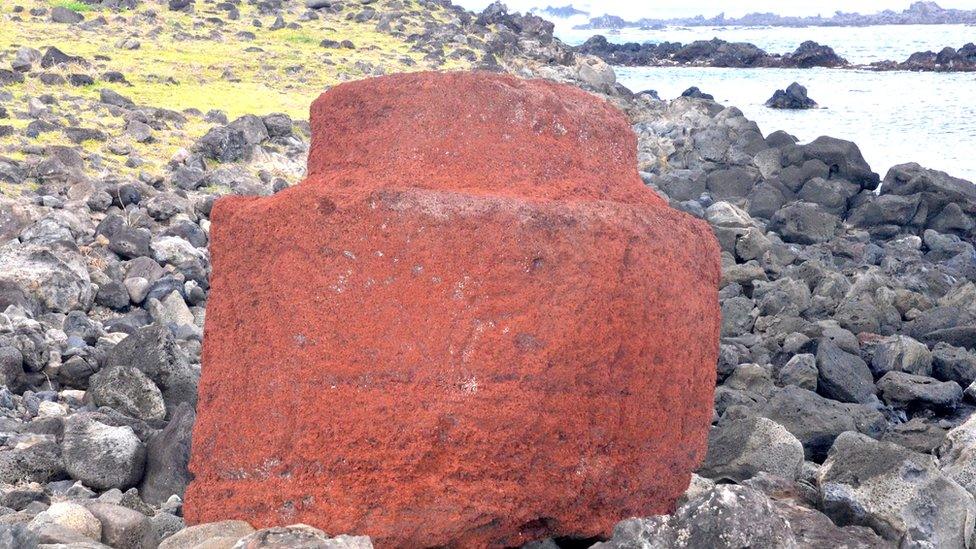

Some red scoria pieces have smaller cylindrical projections on top

The large cylindrical pukaos are made of red volcanic rock called scoria, while the Moai heads are carved from volcanic tuff. The materials were excavated from craters at opposites sides of the island.

In many cases, the giant pukaos were rolled into position as far as 13km away from the quarry where they were sourced. Red scoria is also porous and therefore less dense than tuff, making it easier to raise into position.

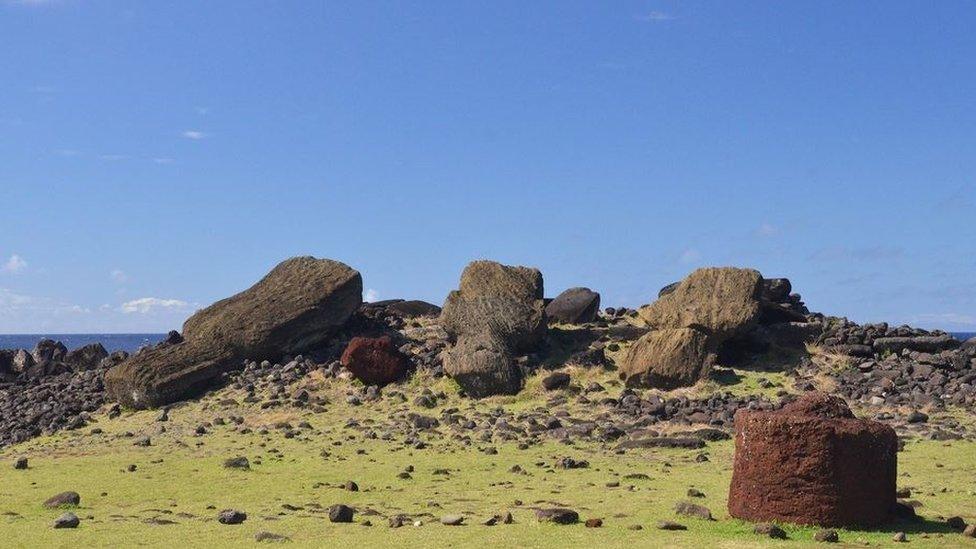

Some of the cylinders were seemingly abandoned during the transport and have been left in the upright wheel positions in which they remain today. The researchers found that the wear and tear markings on these examples also give further proof of transport by rolling.

Researchers used 3D imaging to compare pukao indentations

Previous theories have suggested the transport and production of the statues were linked with deforestation and the eventual collapse of a large population. But the new evidence that this scale of engineering expertise could be accomplished using only a few ropes and small groups of people could further debunk the earlier notions of an "ecocide" in which the Islanders were thought to have overexploited island resources.

"With the building mitigating any sense of conflict, the Moai construction and pukao placement were key parts to the success of the island," said anthropology professor Carl Lipo.

Red scoria's colour would have matched cultural traditions about hats

The prehistoric Rapanui people made nearly 1,000 giant stone statues and carvings, the largest of which weigh 74 tonnes and stand 10m tall - the height of a three-floor building. The Moai were positioned to form a ring around the island, facing inland.

"The hats would be the grand finale - the final showing off of the coherence of the group, the technology and the genius in engineering," Prof Terry Hunt, from the University of Arizona, told BBC News.

"Culturally, the addition of hats is likely related to honouring ancestors. The head is traditionally thought to contain 'mana', so adding the hat provides additional prestige," Prof Lipo said.

Standing Moai on the South Coast of Rapa Nui

The members of the Spanish expedition to Easter Island in 1770 were the first to record their descriptions of the scoria hats. F. A. de Agüera y Infanzon wrote, "the diameter of the crown is much greater than that of the head on which it rests... a position which excited wonder that it does not fall".

In 1917, anthropologist Scoresby Routledge thought the pukao resembled hats after likening them to grass headgear; while Norwegian adventurer Thor Heyerdahl believed them to look more like heads of hair.

Prof Lipo said this incorrect notion came from thinking they were the same elite "red haired" people who built monuments in South America, instead of the Polynesian descended Rapanui society. However, given the "deep tradition of headgear, thinking of pukao as hats is more consistent with what we know about the island," explained Prof Lipo.

The people of Rapa Nui were of Polynesian descent

Many questions remain for the finely crafted figures and the fate of the Rapanui who made them, but the new study sheds light on the unique abilities of our prehistoric relatives.

"These were ancient engineers with a genius that allowed people to walk multi-tonne statues and roll multi-tonne hats - which teaches us about the society's investment in honouring their ancestors. It's quite a remarkable accomplishment," Prof Hunt said.