Antarctica loses three trillion tonnes of ice in 25 years

- Published

Four things you should know about Antarctica

Antarctica is shedding ice at an accelerating rate.

Satellites monitoring the state of the White Continent indicate some 200 billion tonnes a year are now being lost to the ocean as a result of melting.

This is pushing up global sea levels by 0.6mm annually - a three-fold increase since 2012 when the last such assessment was undertaken.

Scientists report the new numbers in the journal Nature, external.

Governments will need to take account of the information and its accelerating trend as they plan future defences to protect low-lying coastal communities.

The researchers say the losses are occurring predominantly in the West of the continent, where warm waters are getting under and melting the fronts of glaciers that terminate in the ocean.

"We can't say when it started - we didn't collect measurements in the sea back then," explained Prof Andrew Shepherd, who leads the Ice sheet Mass Balance Inter-comparison Exercise (Imbie).

"But what we can say is that it's too warm for Antarctica today. It's about half a degree Celsius warmer than the continent can withstand and it's melting about five metres of ice from its base each year, and that's what's triggering the sea-level contribution that we're seeing," he told BBC News.

Andrew Shepherd: "The study incorporates 24 independent satellite assessments"

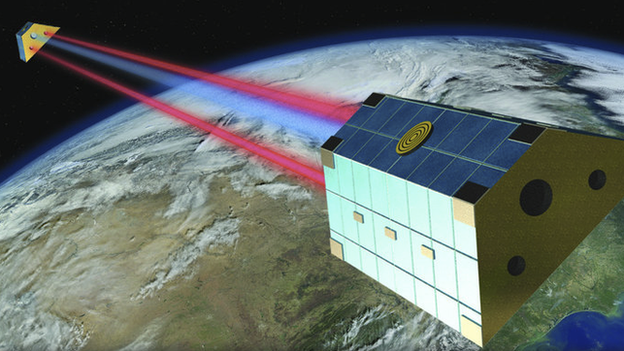

Space agencies have been flying satellites over Antarctica since the early 1990s. Europe, in particular, has an unbroken observation record going back to 1992.

These spacecraft can tell how much ice is present by measuring changes in the height of the ice sheet and the speed at which it moves towards the sea. Specific missions also have the ability to weigh the ice sheet by sensing changes in the pull of gravity as they pass overhead.

Imbie's job has been to condense all this information into a single narrative that best describes what is happening on the White Continent.

Glaciologists usually talk of three distinct regions because they behave slightly differently from each other. In West Antarctica, which is dominated by those marine-terminating glaciers, the assessed losses have climbed from 53 billion to 159 billion tonnes per year over the full period from 1992 to 2017.

On the Antarctic Peninsula, the finger of land that points up to South America, the losses have risen from seven billion to 33 billion tonnes annually. This is largely, say scientists, because the floating ice platforms sitting in front of some glaciers have collapsed, allowing the ice behind to flow faster.

East Antarctica, the greater part of the continent, is the only region to have shown some growth. Much of this region essentially sits out of the ocean and collects its snows over time and is not subject to the same melting forces seen elsewhere. But the gains are likely quite small, running at about five billion tonnes per year.

And the Imbie team stresses that the growth cannot counterbalance what is happening in the West and on the Peninsula. Indeed, it is probable that an unusually big dump of snow in the East just before the last assessment in 2012 made Antarctica as a whole look less negative than the reality.

Globally, sea levels are rising by about 3mm a year. This figure is driven by several factors, including the expansion of the oceans as they warm. But what is clear from the latest Imbie assessment is that Antarctica is becoming a significant player.

"A three-fold increase now puts Antarctica in the frame as one of the largest contributors to sea-level rise," said Prof Shepherd, who is affiliated to Leeds University, UK.

"The last time we looked at the polar ice sheets, Greenland was the dominant contributor. That's no longer the case."

In total, Antarctica has shed some 2.7 trillion tonnes of ice since 1992, corresponding to an increase in global sea level of more than 7.5mm.

Artwork: European satellites in particular have an unbroken record going back to 1992

The latest edition of the journal Nature has a number of studies looking at the state of the continent and how it might change in a warming world.

One of these papers, external, led by US and German scientists, examines the possible reaction of the bedrock as the great mass of ice above it thins. It should lift up - something scientists call isostatic readjustment.

New evidence suggests where this process has occurred in the past, it can actually constrain ice losses - as the land rises, it snags on the floating fronts of marine-terminating glaciers.

"It's like applying the brakes on a bike," said Dr Pippa Whitehouse from Durham University. "Friction on the bottom of the ice, which was floating but has now grounded again, slows everything and changes the whole dynamic upstream. We do think the rebound (in the future) will be fast, but not fast enough to stop the retreat we've kicked off with today's warming.

"Ocean warming is going to make the ice too thin for this process to help."

Pippa Whitehouse: "Push a balloon filled with honey - it rebounds when you remove your hand"

In Imbie's last assessment, the contribution of Antarctica to global sea-levels was considered to be tracking at the lower end of the projections that computer simulations had made of the possible height of the oceans at the end of the century. The new assessment sees the contribution track the upper end of these projections.

"At the moment, we have projections going through to 2100, which is sort of on a lifetime of what we can envisage, and actually the sea-level rise we will see is 50/60cm," said Dr Whitehouse. "And that is not only going to impact people who live close to the coast, but actually when we have storms - the repeat time of major storms and flooding events is going to be exacerbated," she told BBC News.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published14 June 2018

- Published22 May 2018