Source of cosmic 'ghost' particle revealed

- Published

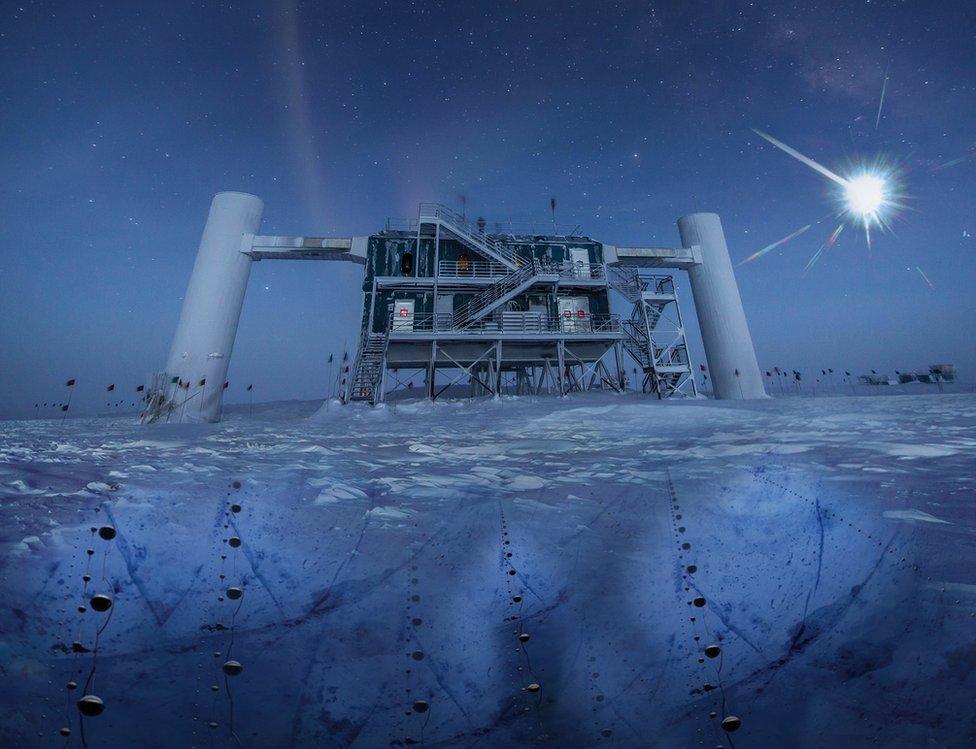

The discovery was made at the IceCube detector in Antarctica

Ghost-like particles known as neutrinos have been puzzling scientists for decades.

Part of the family of fundamental particles that make up all known matter, neutrinos hurtle unimpeded through the Universe, interacting with almost nothing.

The majority shoot right through the Earth as though it isn't even there, making them exceptionally difficult to detect and study.

Despite this, researchers have worked out that many are created by the Sun and even in our own atmosphere. But the source of one high energy group, known as cosmic neutrinos, has remained particularly elusive.

Now, in the first discovery of its kind, it turns out that a distant galaxy powered by a supermassive black hole may be shooting a beam of these cosmic neutrinos straight towards Earth.

Step One: Catch a neutrino

It all starts with IceCube, a highly sensitive detector buried about two kilometres beneath the Antarctic ice, near the Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station.

"In order to get a measurable signal from the tiny fraction of neutrinos that do interact, neutrino physicists need to build extremely large detectors," explains Dr Susan Cartwright, a particle physicist at the University of Sheffield.

Measuring cosmic neutrinos against those created closer to home is, she told BBC News, "like trying to count fireflies in the middle of a firework display".

IceCube is located near the Amundsen Scott base at the South Pole

But on 22 September 2017, one of these neutrinos showed up near IceCube's cubic kilometre array and decided to interact with the surrounding material, creating another particle called a muon.

Lacking the neutrino's stealth mode, this muon crashed through the ice in the same direction as its progenitor, sparking against other atoms along the way and creating a visible trail that IceCube could capture.

"[IceCube] measures this trail of light," explains Prof Albrecht Karle from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, who was involved in the discovery. "We can do that quite precisely, so that we can measure the direction of [the neutrino's] track."

Using this, IceCube was able to work out the approximate region of sky that the particle had been travelling from.

Step Two: Follow it home

Within 43 seconds, an alert was dispatched for telescopes to join in the hunt.

The Very Large Array listened in to the neutrino's source

Two years previously, the IceCube team had decided that rather than hoard their potential findings for publication, they would send out these "astronomy telegrams", inviting other researchers to participate in the chase as soon as an event was detected.

"Traditionally in astronomy we looked at images of the sky, like it was static, but in reality it's a movie. All the time there are flashes and things moving and happening. So instead of publishing a paper and having astronomers look three years later at something we report, we went into real time mode," says Prof Karle.

Eight other observatories trained their eyes and ears on the neutrino's point of origin.

The tricky part, explains Prof Karle, is that even though IceCube can work this out to within half a degree of sky, that is still about the size of the Moon as we see it from the Earth's surface. Such a region can encompass a lot of galaxies and other objects.

However this time, there was good news.

Artwork: a galaxy with a massive black hole at its centre

A galaxy with a "monster" black hole about 100 million times the size of our Sun, was sitting in exactly the right spot.

Step Three: Blazars off the shoulder of Orion

About four billion light years from Earth, just off the left shoulder of the constellation Orion, this galaxy has an intensely bright core caused by the energy of its central black hole.

As matter falls in to the black hole, vast jets of charged particles emerge at right angles, making them massive particle accelerators.

Artwork: The constellation of Orion

"They can extend to almost a million light years, just the jet. Which is of course bigger than the Large Hadron Collider at Cern," laughs Prof Karle.

It is perhaps unsurprising that the neutrino detected by IceCube arrived with 40 times more energy than particles accelerated at Cern, despite its long journey.

This particular galaxy type is known as a blazar, because one of the jets is trained directly towards Earth.

"So we are really in the line of fire. We are staring in to the eye of the monster so to speak," adds Prof Karle.

What's new?

Although not originally high on the list of potential cosmic neutrino sources, this makes for strong evidence that blazars do generate the elusive particles.

"This is extremely exciting news," says Dr Cartwright, who was not involved in the study.

"We can hope that this observation will be followed by the identification of further neutrinos from flaring blazars."

After their initial detection, the IceCube team went back through previous records of neutrino interactions and found that several more had come from the direction of the same galaxy.

"The chance of this excess of neutrinos arising by chance is less than 0.03%," Dr Cartwright adds.

Confirming the discovery via the work of other observatories like the Eso's Very Large Telescope in Chile makes it the latest success for multi-messenger astronomy - detections combining electromagnetic information like visual and radio data with signals like gravitational waves and neutrinos.

Follow Mary on Twitter, external.