Baby snake 'frozen in time' gives insight into lost world

- Published

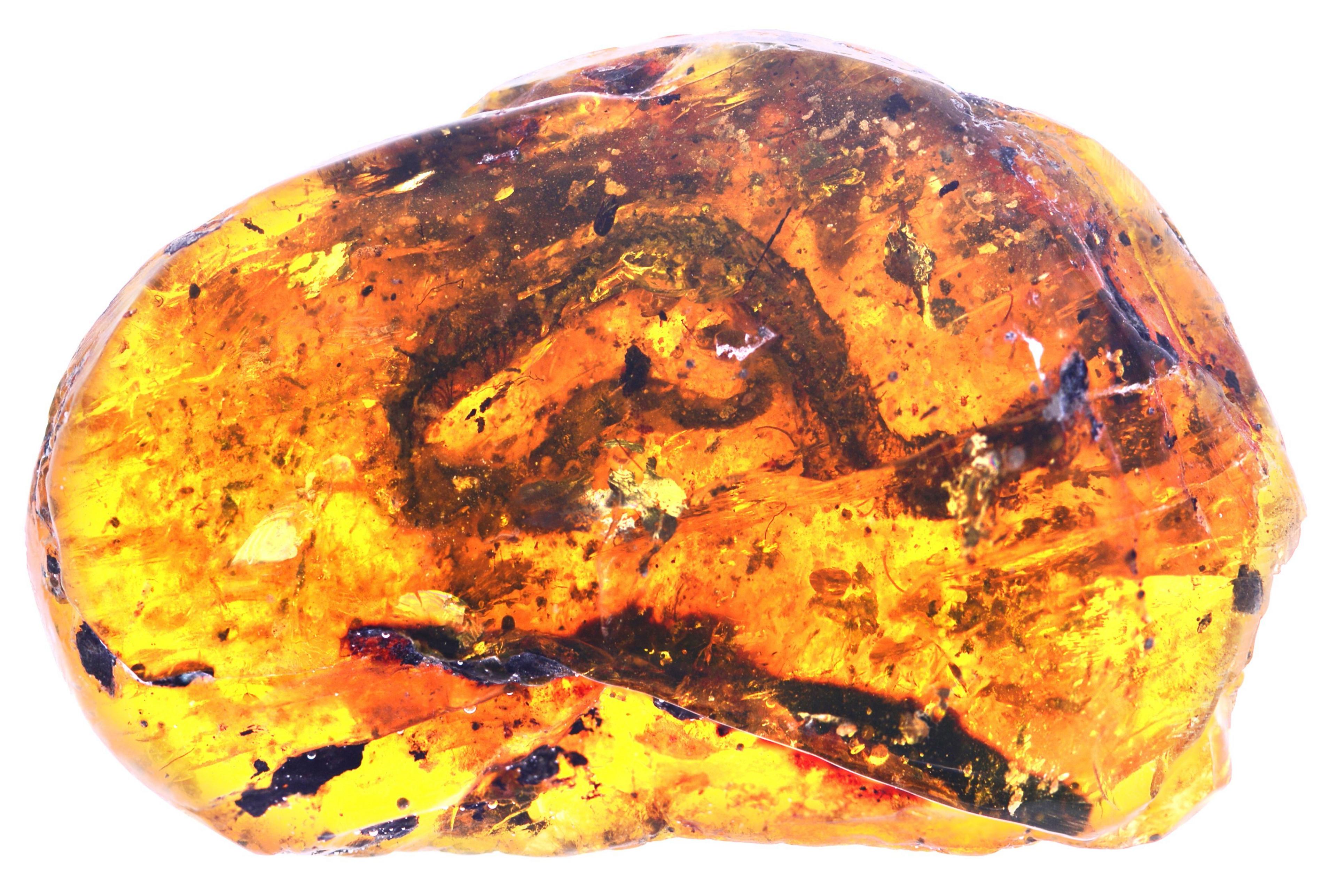

The fossil gives an insight into how snakes became such successful creatures

The fossil of a baby snake has been discovered entombed inside amber.

The creature has been frozen in time for 99 million years.

The snake lived in what is now Myanmar, during the age of the dinosaurs.

Scientists say the snake fossil is "unbelievably rare".

"This is the very first baby snake fossil that we have ever found," Prof Michael Caldwell of the University of Alberta in Canada told BBC News.

What the dawn snake of Myanmar may have looked like

The baby snake lived in the forests of Myanmar during the Cretaceous period. It has been given the name, Xiaophis Myanmarensis, or dawn snake of Myanmar.

A second amber fossil was discovered, which appears to contain part of the shed skin of another much larger snake. It is unclear whether this is a member of the same species.

The skin of a second specimen was found

How did the snake become frozen in time?

The animal became stuck in tree sap, a sticky substance that can preserve skin, scales, fur, feathers or even whole creatures.

"It's the super-glue of the fossil record," said Prof Caldwell.

"Amber is totally unique - whatever it touches is frozen in time inside of the plastic-like resin."

Earliest fossils

Snakes: The oldest known snake fossils date from between 140 million and 167 million years ago, and come from the UK - Durlston Bay in Dorset to be exact. Eophis underwoodi was small - possibly a youngster, and lived in a marshy or swampy environment.

Lizard: A small lizard discovered in rocks from the Italian Alps was confirmed this year as the earliest example of its kind. Megachirella wachtleri lived in the Triassic Period, about 240 million years ago. The find suggested that the group lizards belong to had evolved earlier than previously thought

Dinosaur: The earliest known dinosaur fossil dates to around the same time as the earliest lizard. Nyasasaurus was two to three metres in length and found in the Manda geological formation in Tanzania, East Africa but it's only known from a few bones, so little is understood about it, or its life history. The group it belonged to went on to dominate the Earth for 165 million years.

Horse: The earliest mammal that resembles a horse is Eohippus, which was found at North American sites such as the Wind River Basin in Wyoming. It lived around 52 million years ago and was only about the size of a fox. However, true horses only appear around 20 million years ago, by which time they had evolved to be the size of small ponies.

Human: It depends what you mean by human. But if we take that to apply to species under the biological grouping known as Homo, the oldest example is a jawbone fragment from the Afar Region of Ethiopia and dating to between 2.80 and 2.75 million years ago.

What does the new discovery tell us about these iconic creatures?

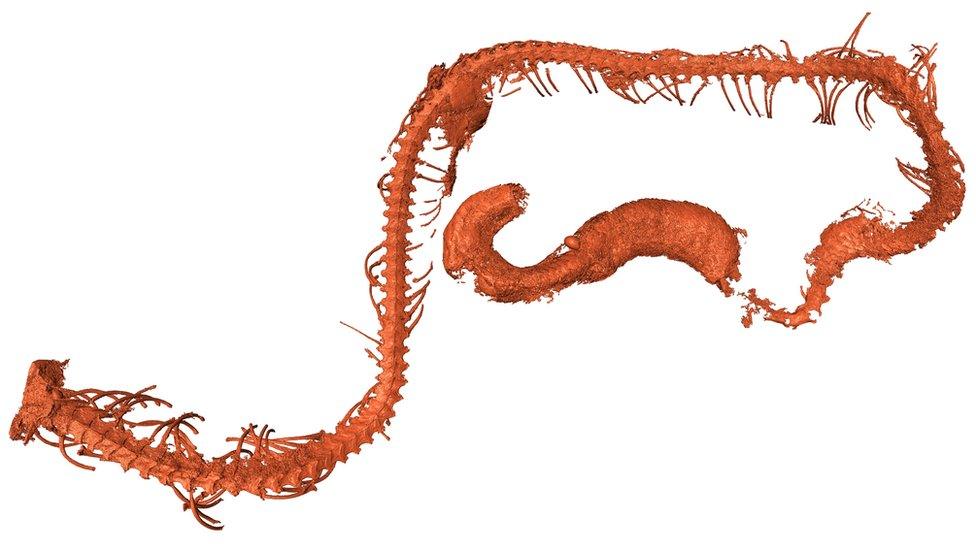

The snake's body can be seen inside the chunk of amber, made up of 97 vertebrae plus attached ribs. Intriguingly, the snake's head is missing.

The creature's bones were analysed inside a synchrotron, an extremely powerful source of X-rays, and compared with those of living snakes.

Anatomical features suggest development of the backbone of snakes appears to have changed little in nearly 100 million years.

Scientists say the snake may have survived for tens of millions of years in a primitive state, before going extinct.

The snake is similar in size to living species, such as the Asian Pipe Snake

What do we know about where it lived?

Fragments of plants and insects found inside the amber confirm that the snake lived in forests.

This has not been shown before for this time period, as the few other fossil snakes discovered come from rocks associated with rivers or the sea.

Dr Ricardo Pérez-de la Fuente of the Oxford University Museum of Natural History, who is not connected with the research team, said the find gives "invaluable developmental and evolutionary data on ancient snakes".

The chunk of amber that contains the baby snake

What is so special about amber fossils?

Myanmar is seen as a treasure trove of exciting fossil discoveries from the Cretaceous period, between 145 and 66 million years ago.

Recent finds include, external, , external and a haul of prehistoric frogs.

The new discovery is reported in the journal Science Advances.

Follow Helen on Twitter, external.

- Published5 February 2018

- Published14 June 2018