Ocean wilderness 'disappearing' globally

- Published

Scientists have mapped marine "wilderness" areas around the world for the first time.

These are regions minimally impacted by human activities such as fishing, pollution and shipping.

The team, led by researchers in Australia, found that just 13.2% of the world's oceans could be classed as wilderness - most in international waters, away from human populations.

Very few coastal areas met the criteria, including coral reefs.

Reefs are some of the most biodiverse habitats in the ocean, as they are home to a great number of different plant and animal species. They are thought to be vital areas for marine life.

Coral reefs are known to be under threat from climate change and warming oceans

What makes a wilderness?

"It's a place where the environment and ecosystem is acting in basically an undisturbed way that's free from human activity," explained lead author Kendall Jones.

"Studies have shown that places free from intense levels of human activity have really high levels of biodiversity and high genetic diversity [but] we didn't have an idea of where across the globe these intact places could still be found," the Wildlife Conservation Society researcher told BBC News.

Jones and other scientists set out to analyse the impact of 15 different human activities or "stressors" on global ocean environments, in order to map these regions. Areas that experienced the least impact - the bottom 10% - were classed as wilderness.

Data from satellites, ship tracking and pollution reports from individual countries were analysed.

Wilderness areas may be home to a more diverse range of species than places impacted by human activity

Dr Rachel Hale from the University of Southampton, observed that "marine wildernesses are largely overlooked in terms of conservation priorities when compared to terrestrial ones, and it is extremely interesting to see where in the world these lie and what habitats they cover.

"They could be important corridors connecting habitats and species populations," added Dr Hale, who was not involved in the study.

How much is left?

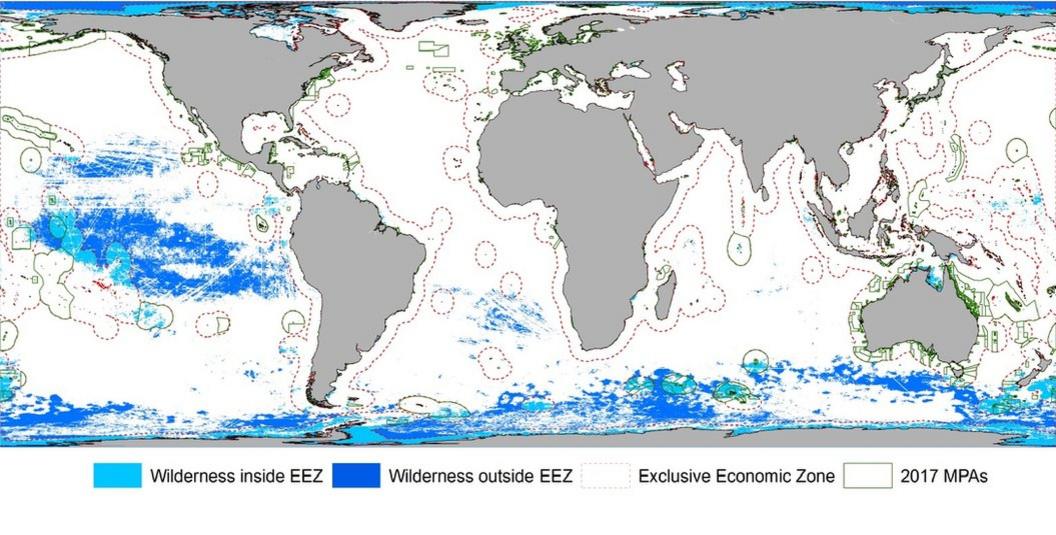

The team found that most of the areas they defined as wilderness fell within the Arctic, Antarctic and around Pacific Island nations, or in the open ocean, where human activity is more limited.

Despite their conservation status, marine protected areas (MPAs) appear to host just 4.9% of global marine wilderness.

Marine wilderness areas (blue) are largely outside the economic zones of individual countries, and of marine protected areas (green)

Mr Jones also noted that wilderness areas exposed by the decline of sea ice in the Arctic are now potentially vulnerable to anthropogenic impacts.

What can be done?

Although Mr Jones points out that fishing is one of the most significant direct impacts that humans can have on ocean ecosystems, many of the problems being caused originate on land.

Runoff of nutrients from farming fertilisers, chemicals from poorly controlled industrial production, and the influx of plastic pollution from rivers are all disrupting ocean life.

"Plastic pollution is one of the big things that we want to work out a way to get data on," he told the BBC.

"It's so widespread and so hard to manage that we really want to get a good idea of where it is and where is most affected."

Plastic pollution in the oceans impacts many different species

The UN are currently considering a legally binding addition to the Convention on the Law of the Sea, which would mandate conservation and sustainable use of international waters - currently not protected.

The first of four conferences to determine the details will take place in September 2018.

Mr Jones welcomes this: "It's good that the international community is starting to recognise the need for improved management of international waters."

However Dr Hale points out that the issues could prove more complex, with many problems traversing legal and international boundaries.

"Formal protection of these wilderness areas would not be able to protect them from some stressors such as climate change and invasive species," she told the BBC.

"We should prioritise conservation actions in at-risk and/or biologically important areas, and identifying these areas within the identified marine wilderness areas would be a positive next step."

The findings are published in Current Biology, external.

Follow Mary on Twitter, external.