The Meg: the myth, the legend (the science)

- Published

The Meg, Hollywood's latest shark tale, is opening wide this week in anticipation of summer audiences in the mood for a scare.

Proposing that the extinct Megalodon, a large prehistoric relative of the great white shark, has survived to the present day, the film follows its subsequent encounter with humanity.

But how much do we really know about the giant predator?

And what impact do shark attack films have on their real subjects?

Shark researcher and Megalodon expert Catalina Pimiento from Swansea University wants to break down a few myths.

Megalodon is very much still alive in The Meg

Dead or alive?

"It's very much extinct," says Dr Pimiento. "There's no way it can be still around."

Researchers have pinned the date of Megalodon's extinction at about 2.6 million years ago - roughly when its cousin the great white shark was just becoming established.

In The Meg, Megalodon has survived the ages in a previously unknown (to humans) area of deep ocean off the coast of China.

However, Dr Pimiento points out that Megalodon likely lived in water no more than 200 metres deep, in and around coastal areas.

We would, she says, have noticed something of Megalodon's size if it was swimming off our shores.

What did it look like?

Much of what we know about the species comes from its teeth, which are some of the only remains that have been preserved.

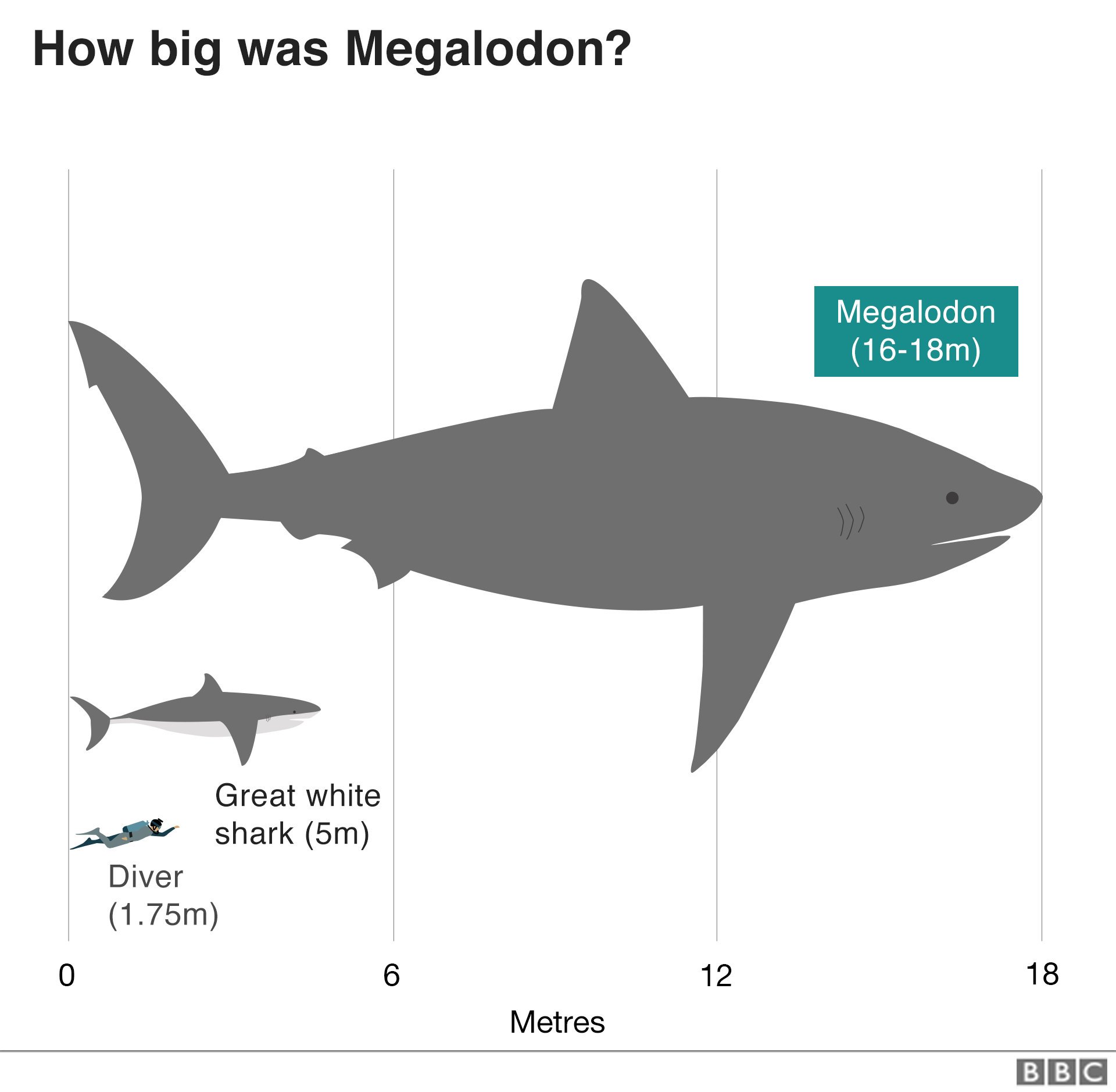

Estimates of its full body length range from at least 13 metres up to a maximum of 18 metres, or almost the length of two double decker buses.

While this dwarfs great white sharks, it's not quite the submarine-crunching 25 metres featured in The Meg.

What did it eat?

Melagodon's remarkable size is fascinating to researchers, as an animal that large would have had to work very hard to find enough food.

"If you think about that on land for example, all the largest animals are herbivores... if you're that big then you need to eat a lot of prey and you need to hunt a lot to find that much food," explains Dr Pimiento.

Modern whale sharks can grow up to Megalodon's length of 18 metres, but only eat plankton

"So that's why Megalodon is so amazing; because it was a predator and it was huge!"

Although it's very difficult to know much about how Megalodon would have moved and behaved, Dr Pimiento has her suspicions about what kind of hunter it would have been. She hopes to build a 3D model of the shark in order to study this in more detail.

"If I had to guess, I wouldn't think it was an agile predator. It could even have been more of a scavenger. Sharks are opportunistic, and they will eat anything they can. If they can hunt, they will hunt. If they see a carcass, they will eat the carcass."

So even if we had lived at the same time, a small human snack might not have been worth the energy.

The three largest teeth come from Megalodon; the others are from modern shark species

Why did it die out?

There's no evidence that Megalodon's remarkable size was the cause of its extinction, but food was almost certainly a factor.

Rapidly changing sea levels about 2.6 million years ago impacted the coastal ecosystem that the giant shark inhabited.

Over the course of a few million years, around 36% of sharks, sea turtles, sea birds and marine mammals became extinct.

Megalodon was the last of its lineage of giant sharks, and it was succeeded by smaller, more agile hunters like the great white.

All publicity is good publicity?

Although The Meg's creators put a good deal of research into reviving Megalodon, before adding some artistic licence, previous shark attack films have been thought to affect their real life counterparts.

The great white shark was portrayed as a vengeful killer in Jaws (1975)

"Movies have such an impact," says Dr Pimiento.

"We shouldn't take them lightly. Jaws had a huge impact on the protection of sharks, and a role in giving them a bad reputation. People don't realise how vulnerable they are."

It was speculated that shark populations off the US coast were affected after Steven Spielberg's 1975 blockbuster, with fishers setting out to catch "trophy sharks."

Nowadays, sharks are threatened by human encroachment on their hunting grounds, competing for the same prey.

If Megalodon had survived to encounter humans, it's likely we would be the far greater danger.

Follow Mary on Twitter, external.