Could Nasa's James Webb Space Telescope detect alien life?

- Published

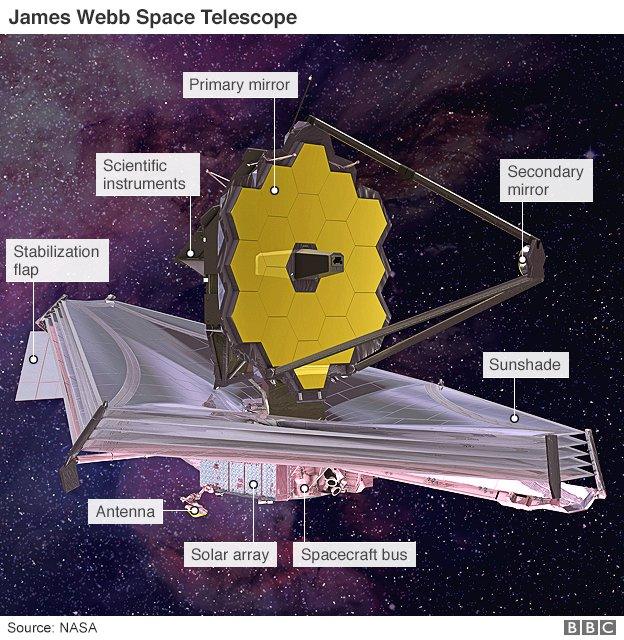

Webb contains novel technologies that have never previously been flown in space

If it does launch as currently scheduled in 2021, it will be 14 years late. When finally in position, though - orbiting the Sun 1.5 million km from Earth - Nasa's James Webb Space Telescope promises an astronomical revolution.

The US space agency boasts that it will literally "look back in time to see the very first galaxies that formed in the early Universe".

As if those claims were not bold enough, scientists have now surmised that the eventual successor to the world famous and beloved Hubble Space Telescope may - thanks to its 6.5m golden mirror and exquisitely sensitive cameras - have a another extraordinary talent.

The JWST, as it is called, may be able to look for signs of alien life - detecting whether atmospheres of planets orbiting nearby stars are being modified by that life.

Despite this, the project to build it narrowly survived cancellation by the US Government in 2011. That was in no small part down to its (perhaps appropriately) astronomical cost - an estimated $10bn rather than its originally planned $1bn.

Back on Earth, however, astronomers - including the University of Washington team who proposed "life-detection" observations using the telescope - are unerringly thrilled at the prospect of its launch.

How do you detect life on distant planets?

University of Washington astronomer Joshua Krissansen-Totton and his team have looked into whether the telescope could detect signs of what they call "biosignatures" in the atmospheres of planets that are orbiting a nearby star.

"We could do these life-detection observations in the next few years," says Mr Krissansen-Totton.

The basis for this search may lie in JWST being so sensitive to light that it could pick up so-called "atmospheric chemical disequilibrium".

Earth's atmosphere would change if all life was suddenly removed

It may not be a catchy term, but it is an idea with a long heritage, promoted by celebrated scientists James Lovelock and Carl Sagan.

The reasoning is that if all life on Earth disappeared tomorrow, the many gases which make up our atmosphere would undergo natural chemical reactions, and the atmosphere would slowly revert to a different chemical mixture.

It is continually held away from this state by organisms on our planet expelling waste gases as they live.

Because of this, searching for signs of oxygen (or its chemical cousin ozone) has long been thought to be a good way of finding life. But this does rest on the assumption that extraterrestrial life runs by the same biological rules as our own.

It might not. Therefore, assessing atmospheric chemical disequilibrium - looking for other gases and figuring out how far out of kilter from "normal' a planet's atmosphere sits - could be key to finding alien life of any kind.

The chemical make-up of the atmosphere of a planet orbiting another star can be measured in light by carefully measuring the minuscule dip in starlight as the planet passes between us and the star during the planet's orbit. The gases in the planet's atmosphere cause the light reduction to vary with the wavelength - or colour - of light, revealing information about how much of each chemical is present.

Where is the best place to look?

Mr Krissansen-Totton simulated the data that would be obtained if JWST were to look at planets orbiting a small Jupiter-sized star called TRAPPIST-1, about 39.6 light-years away from our Sun. This star caused a sensation in 2017 when it was discovered to host seven Earth-sized planets, several of which could possess liquid water, and hence might be a good bet for hosting life.

The Washington researcher predicts that James Webb could measure the amounts of methane and carbon dioxide in the atmosphere of the fourth planet, TRAPPIST-1e, from the dips in light at wavelengths affected by these gases.

It would be a tough measurement of an unimaginably tiny signal, but Cornell University astronomer Prof Jonathan Lunine, who was not involved in this study, is excited by the prediction, saying "they make the case that this can really be done with JWST".

All seven planets are thought to have Earth-like characteristics (Photo credit: Nature)

Once the measurement is made, though, Mr Krissansen-Totton explains, "you can then ask the question: do we know of any non-biological processes" that could produce that effect?"

Planetary atmospheres, including our own, he points out, can also be modified by non-biological processes, such as volcanic activity. So, if the atmosphere of TRAPPIST-1e was found to be awry, researchers would then need to rule out any non-biological effects before declaring the existence of extraterrestrial life.

Mr Krissansen-Totton says that "that kind of confirmation is going to require multiple observations, to really make a totally solid case".

"But if we detect something that we don't have an alternative explanation for, I think that would be an incredibly exciting discovery."

Who else will be doing this?

For now, the telescope's golden mirror remains securely locked in a lab in California, and astronomers must continue to wait for these possibilities to be explored.

JWST will be joining a host of new facilities that will subject planets around other stars to some serious scrutiny over the next few decades.

Huge ground-based telescopes in Hawaii and Chile are also planned, and the European Space Agency's UK-led Ariel mission, designed to probe the atmospheres of planets around other stars, will blast off in the late 2020s.

Prof Lunine says: "I think that we're in a remarkable time for understanding our Universe and exploring the cosmos, and James Webb is going to take the next step in that.

"It is going to be truly worth it."

Prof Gillian Wright, principal scientist on the telescope's UK-led Mid-InfraRed instrument, agrees. "We've never had access to something this big in space before," she says.

"To say a telescope will open up new windows on the Universe sounds kind-of cliched, but with James Webb it's really true."

JWST is led by Nasa but is a joint venture with the European and Canadian space agencies. Dr Jonathan Nichols is a planetary scientist from the University of Leicester and a 2018 British Science Association media fellow

- Published27 June 2018

- Published22 February 2017