NovaSAR: UK radar satellite launches to track illegal shipping activity

- Published

S1-4 and NovaSAR pictured just before being enclosed at the top of their Indian rocket

The first all-British radar satellite has launched to orbit on an Indian rocket.

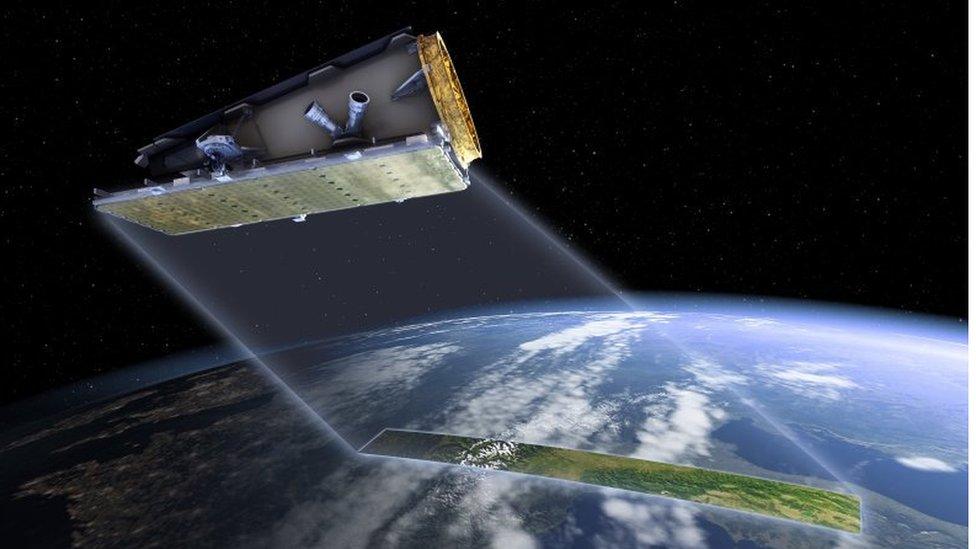

Called NovaSAR, it has the ability to take pictures of the surface of the Earth in every kind of weather, day or night.

The spacecraft will assume a number of roles but its designers specifically want to see if it can help monitor suspicious shipping activity.

Lift-off from the Satish Dhawan spaceport occurred at 17:38 BST.

NovaSAR was joined on its rocket by a high-resolution optical satellite - that is, an imager that sees in ordinary light.

Known as S1-4, this spacecraft will discern objects on the ground as small as 87cm across. Both it and NovaSAR were manufactured by Surrey Satellite Technology Limited of Guildford.

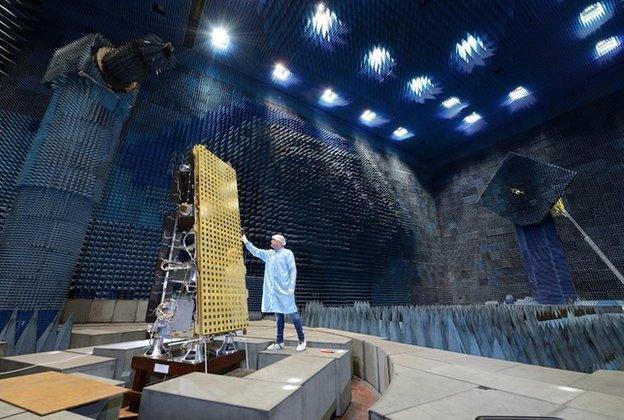

NovaSAR has something of the look of a cheese-grater

UK engineers have long had expertise in space radar but their technology has previously always gone on broader missions, such as those for the European Space Agency. NovaSAR, which has the distinctive shape of a cheesegrater, is uniquely British, however.

Its radar instrument was developed for SSTL by Airbus in Portsmouth. The mission incorporates low-cost, miniaturised components and will aim to demonstrate a more affordable approach to radar imaging.

It will operate in a number of modes for applications that include the detection of oil spills, flood and forestry monitoring, disaster response, and crop assessment.

Portsmouth viewed by the NovaSAR radar instrument when it was flown on an aeroplane

But perhaps its most interesting role will be in maritime observation.

The satellite is equipped with a receiver that can pick up Automatic Identification System (AIS) radio signals. These are the positional transmissions that large ships are obliged to broadcast under international law.

Vessels that tamper with or disable these messages very often are engaged in smuggling or illegal fishing activity. If such ships appear in NovaSAR's pictures, they will be reported to the authorities.

"We are very interested in this maritime mode, which is a 400km-plus swath mode," said Luis Gomes, the chief technology officer at SSTL.

"It is important to be able to monitor large areas of the ocean - something we don't do at the moment. We all saw with the Malaysian airline crash in the Indian Ocean the difficulty there was in monitoring that vast area. We can do that kind of thing with radar and NovaSAR is good for that," he told BBC News.

Luis Gomes: "Nobody currently is monitoring vast areas of ocean"

The NovaSAR project was initiated inside SSTL in 2008/9. Back then the idea of a radar satellite that measured 3m by 1m was regarded as something of a breakthrough because, up that point, such spacecraft had been big, power-hungry beasts that cost a lot of money.

It is a little unfortunate therefore that the programme got delayed because in the meantime others have also managed to package radar systems into small volumes. The Finnish start-up Iceye has a platform flying now that is the size of a suitcase. And an American company called Capella is promising a radar satellite that is not much bigger than a shoebox.

But radar expert Martin Cohen from Airbus is unperturbed by these developments.

"NovaSAR is still a step change, certainly for Airbus in terms of what you can do for a particular amount of money. But while we've been waiting for a launch, we haven't stood still," he said. "We've done lots of work on the next generation.

"NovaSAR is just the first in a family of instruments that will offer different capabilities, such as finer resolutions and other parameters; and we will be putting those capabilities on smaller spacecraft than NovaSAR."

S1-4 is a copy of previous SSTL optical satellites, but it will see finer detail on the ground

The satellite, as presently configured, will operate in the S-band (3.2 gigahertz), giving a best resolution of 6m with a swath width of 15-20km. Future variants will go to the higher-frequency X-band and sense features on the ground as small as a metre across, and less.

The Indian Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle (PSLV) was programmed to put NovaSAR and S1-4 into an orbit that is 580km above the Earth.

S1-4 will be taking pictures of China for Twenty First Century Aerospace Technology (21AT). This company, based in Beijing, will use the data in the Asian nation to help with urban planning, working out crop yields, pollution monitoring and doing biodiversity assessments, among many other applications.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published26 September 2017

- Published3 October 2011