Fossil preserves 'sea monster' blubber and skin

- Published

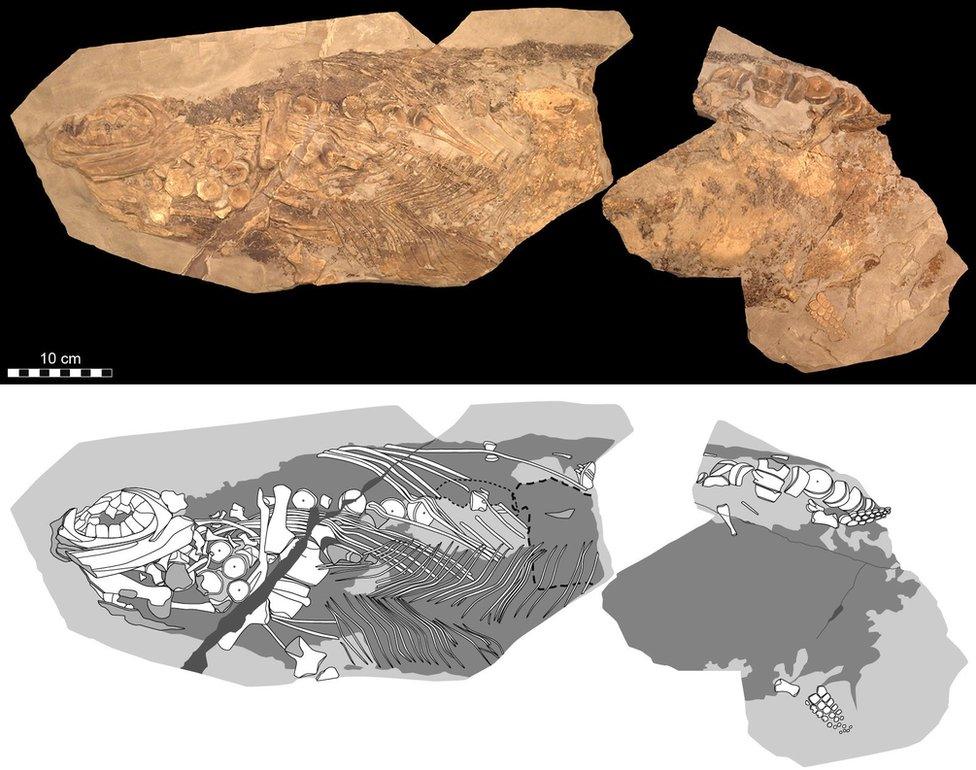

The fossil ichthyosaur comes from the Holzmaden quarry in south-west Germany

Scientists have identified fossilised blubber from an ancient marine reptile that lived 180 million years ago.

Blubber is a thick layer of fat found under the skin of modern marine mammals such as whales.

Its discovery in this ancient "sea monster" - an ichthyosaur - appears to confirm the animal was warm-blooded, a rarity in reptiles.

The preserved skin is smooth, like that of whales or dolphins. It had lost the scales characteristic of its ancestors.

The ichthyosaur's outer layer is still somewhat flexible and retains evidence of the animal's camouflage pattern.

The reptile was counter-shaded - darker on the upper side and light on the underside. This counter-balances the shading effects of natural light, making the animal more difficult to see.

"Ichthyosaurs are interesting because they have many traits in common with dolphins, but are not at all closely related to those sea-dwelling mammals," said co-author Mary Schweitzer, professor of biological sciences at North Carolina State University (NCSU).

Their similar appearance suggests that ichthyosaurs and whales evolved similar strategies to adapt to marine life - an example of convergent evolution.

Prof Schweitzer said: "They have many features in common with living marine reptiles like sea turtles, but we know from the fossil record that they gave live birth, which is associated with warm-bloodedness."

Most reptiles today are cold-blooded, meaning their body temperature is determined by the warmth of their surroundings. Blubber helps some marine animals maintain a high body temperature regardless of the ocean water temperature.

Co-author Johan Lindgren, from Lund University in Sweden, told BBC News: "Blubber is found in living marine mammals but notably also adult individuals of the leatherback sea turtle. Its primary role in all of these animals seems to be insulation, and the leatherback is unique in many aspects.

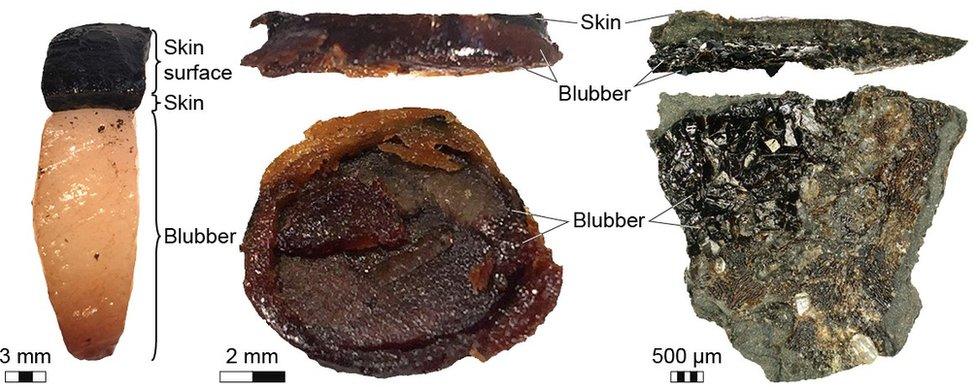

Comparisons between artificially matured modern porpoise blubber and skin and the equivalent from a fossil ichthyosaur.

"It has metabolic rates that are higher than are those of typical reptiles, and a suite of measures for heat retention and control, and collectively these enable adult leatherbacks to venture into cold water environments.

"So, ichthyosaurs were able to control their body temperature at least as well as leatherbacks, but then it is hard to say if they were fully endothermic (warm-blooded) or not."

The researchers identified the blubber and skin remains on a well-preserved ichthyosaur specimen held by the Urweltmuseum Hauff in Germany, external. It was discovered in Holzmaden quarry, in the country's south-west, which has produced many other well-preserved fossils from the Jurassic Period.

The fossil was subjected to an exhaustive analysis of its microscopic structure and molecular composition.

"Both the body outline and remnants of internal organs are clearly visible," said co-author Johan Lindgren, from Lund University in Sweden.

"Remarkably, the fossil is so well-preserved that it is possible to observe individual cellular layers within its skin."

The researchers identified cell-like microstructures which probably held pigment, and an internal organ thought to be the animal's liver.

The blubber-like material contained fragments of fatty acid molecules.

"This is the first direct, chemical evidence for warm-bloodedness in an ichthyosaur, because blubber is a feature of warm-blooded animals," said Prof Schweitzer.

To provide additional support for this idea, the researchers artificially matured the blubber of a modern porpoise, exposing it to high temperatures and pressures - as it would be during the process of fossilisation.

Artwork: The fossil belongs to a type of ichthyosaur called Stenopterygius

The resulting "matured" porpoise blubber shared many features with the fossilised version.

As for the ichthyosaur's skin, the camouflage pattern would have provided protection from Jurassic predators such as flying pterosaurs, attacking from above, and pliosaurs (even bigger marine reptiles), which would have attacked from below.

Dr Lindgren said: "Given the density of pigment cells, and the fact that they occur in both the epidermis and dermis, we hypothesise that ichthyosaurs had a really dark dorsal (upper) skin, which is also what you see in many extant whales that are deep divers (as ichthyosaurs) and venture into cold, arctic regions (as did ichthyosaurs).

"A melanic (dark) colouration would benefit ichthyosaurs as a UV protection while at the sea surface, but could perhaps also help ichthyosaurs thermoregulate as is the case in the leatherback sea turtle."

Losing the scales and evolving smooth skin would also have helped ichthyosaurs manoeuvre more easily underwater.

Johan Lindgren said the still-flexible skin meant the specimen must have been fossilised so fast that organic molecules were trapped inside the mineral component of the fossil.

"Soft tissues, such as skin, have hitherto been considered to be so labile (easily broken down) that the only way they can survive is via full replacement by minerals. However, as it turns out, when these minerals are removed, some of the original organics remain," Dr Lindgren explained.

The results are published in the journal Nature., external

Follow Paul on Twitter., external