Climate change: Arctic reindeer numbers crash by half

- Published

A warmer Arctic has less food and more insects, making it a much worse environment for caribou

The population of wild reindeer, or caribou, in the Arctic has crashed by more than half in the last two decades.

A new report on the impact of climate change in the Arctic revealed that numbers fell from almost 5 million to around 2.1 million animals.

The report was released at the American Geophysical Research Union meeting.

It revealed how weather patterns and vegetation changes are making the Arctic tundra a much less hospitable place for reindeer.

Reindeer and caribou are the same species, but the vast, wild herds in northern Canada and Alaska are referred to as caribou.

It is these herds that are faring the worst, according to scientists monitoring their numbers. Some herds have shrunk by more than 90% - "such drastic declines that recovery isn't in sight", this Arctic Report Card, external stated.

Other stories from the AGU meeting you might like:

Why is a warmer Arctic worse for reindeer?

There are multiple reasons.

Prof Howard Epstein, an environmental scientist from the University of Virginia, who was one of the many scientists involved in the research behind the Arctic Report Card, told BBC News that warming in the region showed no signs of abating.

"We see increased drought in some areas due to climate warming, and the warming itself leads to a change of vegetation."

The Arctic is greening, but that is not good news for reindeer

The lichen that the caribou like to eat grows at the ground level. "Warming means other, taller vegetation is growing and the lichen are being out-competed," he told BBC News.

Another very big issue is the number of insects. "Warmer climates just mean more bugs in the Arctic," said Prof Epstein. "It's said that a nice day for people is a lousy day for caribou.

"If it's warm and not very windy, the insects are oppressive and these animals spend so much energy either getting the insects off of them or finding places where they can hide from insects."

Rain is a major problem, too. Increased rainfall in the Arctic, often falling on snowy ground, leads to hard, frozen icy layers covering the grazing tundra - a layer the animals simply cannot push their noses through in order to reach their food.

Can anything be done?

At the global scale, this comes down to reducing carbon emissions and limiting temperature increase.

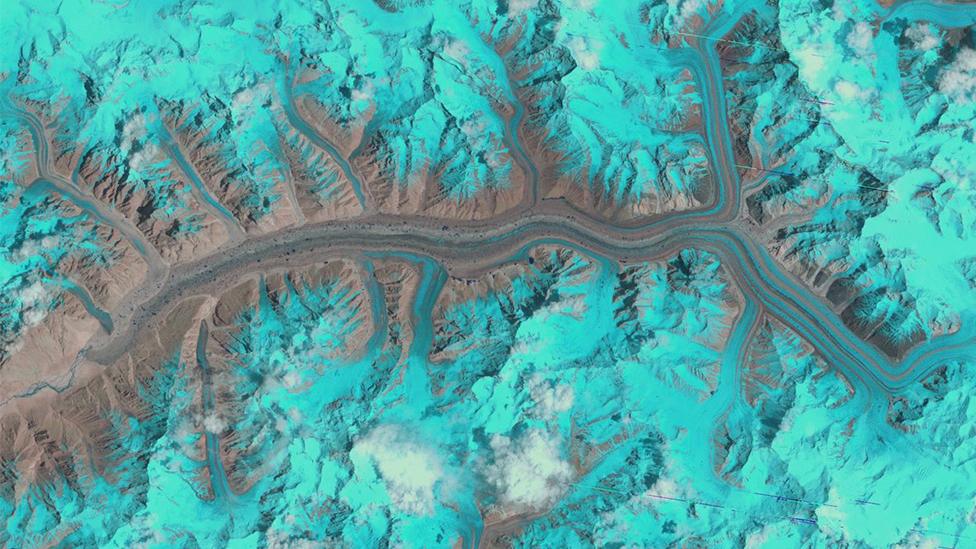

The Arctic Report Card revealed that the region was entering uncharted territory due to climate change

But scientists say we have opened the door on the "world's freezer" and the growing pile of evidence suggests warming in the Arctic will continue. The aim of this and other research in the region is to understand its impacts and learn how to adapt to a changing climate.

The report, compiled by the US National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (Noaa), is now in its 13th year and the administration's Arctic research programme manager, Emily Osborne, said the region was now in "uncharted territory".

"In all the years of publishing the report card, we see the persistence of the warming continuing to mount," she said. "And this is contributing to extreme weather events elsewhere in the world."

Some other key points from the report included:

Plastic pollution: tiny microplastic contamination is on the rise in the Arctic, posing a threat to seabirds and marine life that can ingest debris.

Air temperature: For the past five years (2014-18) temperatures have exceeded all previous records since 1900.

Sea ice thinning: In 2018 Arctic sea ice remained younger, thinner, and covered less area than in the past.

Toxic blooms: Warming Arctic Ocean conditions are coinciding with an expansion of harmful algal blooms in the ocean, which threaten food sources.

Also here at AGU, scientists have revealed that East Antarctica's glaciers have begun to "wake up" and show a response to warming. This is evidence of unprecedented climate-driven change at the top and bottom of the planet.

The 2017 'Arctic Report' showed that sea ice more than four years old has largely disappeared in the Arctic

- Published13 December 2017

- Published10 December 2018