Indonesia tsunami: How a volcano can be the trigger

- Published

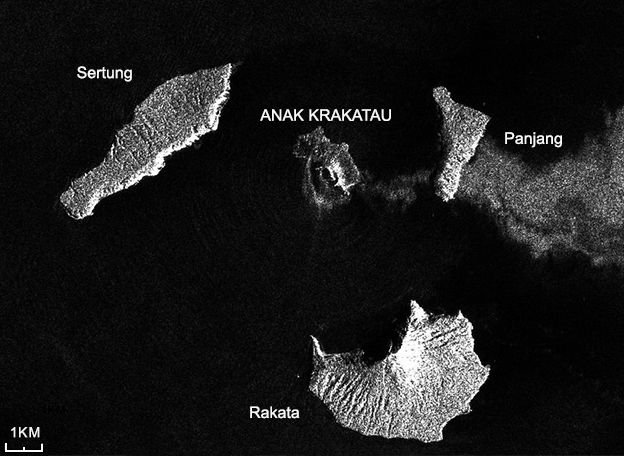

Europe's Sentinel-1 satellite shows the western side of the volcano changed shape

Nobody had any clue. There was certainly no warning. It's part of the picture that now suggests a sudden failure in the west-southwest flank of the Anak Krakatau volcano was a significant cause of Saturday's devastating tsunami in the Sunda Strait.

Of course everyone in the region will have been aware of Anak Krakatau, the volcano that emerged in the sea channel just less than 100 years ago. But its rumblings and eruptions have been described by local experts as relatively low-scale and semi-continuous.

In other words, it's been part of the background.

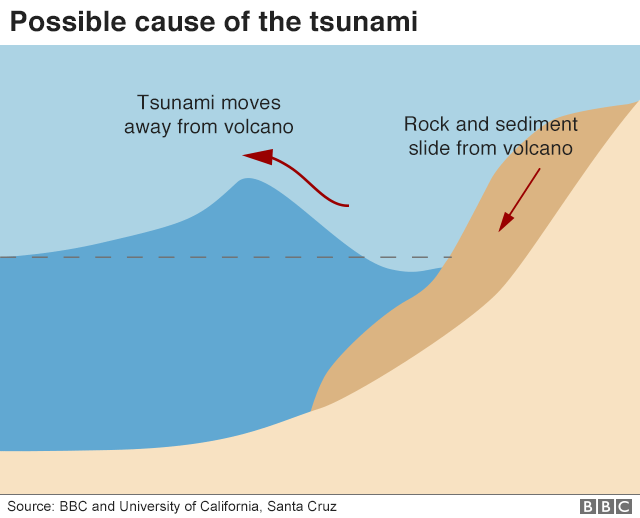

And yet it is well known that volcanoes have the capacity to generate big waves. The mechanism as ever is the displacement of a large volume of water.

The first satellite imagery returned after the event on Saturday points strongly to a collapse in a 64 hectare segment of the west-southwest flank of the volcano during an eruption. This would have sent millions of tonnes of rocky debris into the sea, pushing out waves in all directions.

Anak Krakatau has been rumbling for years

Prof Andy Hooper from Leeds University, UK, is a specialist in the study of volcanoes from orbit. He had little doubt in the interpretation when examining the pictures from Europe's Sentinel-1 radar spacecraft.

"As well as an increase in the size of the crater, there are new dark features on the west side indicating steep-sided scarps in shadow, presumably due to collapse; as well as changes in the coastline."

The comparison between Saturday's imagery and Sentinel pictures acquired before the tsunami are telling.

But the precise anatomy of this event - what happened above the sea surface and below - will not be known until teams can get into the area of the volcano to do a proper survey, and at the moment that is too dangerous. Further collapse could kick off more tsunamis.

Scientists have had concerns for some time about Anak Krakatau, the edifice that has grown in place of the infamous Krakatau mountain that blew itself apart on the same spot in 1883.

One group even modelled what would happen in a collapse of the southwest flank, external - the side of today's volcano considered to be the most unstable.

Waves that were tens of metres high would hit the nearby islands of Sertung, Panjang and Rakata in less than a minute, the team found.

As these waves spread out across the Sunda Strait, they would dissipate, though, coming ashore at one to three metres in height.

The projected scenario is uncanny, particularly in the timing of the inundation. Tide gauges in the Sunda Strait recorded high water around half an hour after the onset of Anak Krakatau's latest eruptive activity, at roughly 21:00 local time (14:00 GMT) on Saturday evening.

Raphaël Paris, one of the authors of the study, issued a statement through the European Geosciences Union. He said: "The volume of collapse simulated is larger than what occurred Saturday (fortunately) and our scenario can thus be considered as a worst-case scenario.

"However, there is a big uncertainty on the stability of the volcanic cone now and the probability for future collapses and tsunamis is perhaps non negligible."

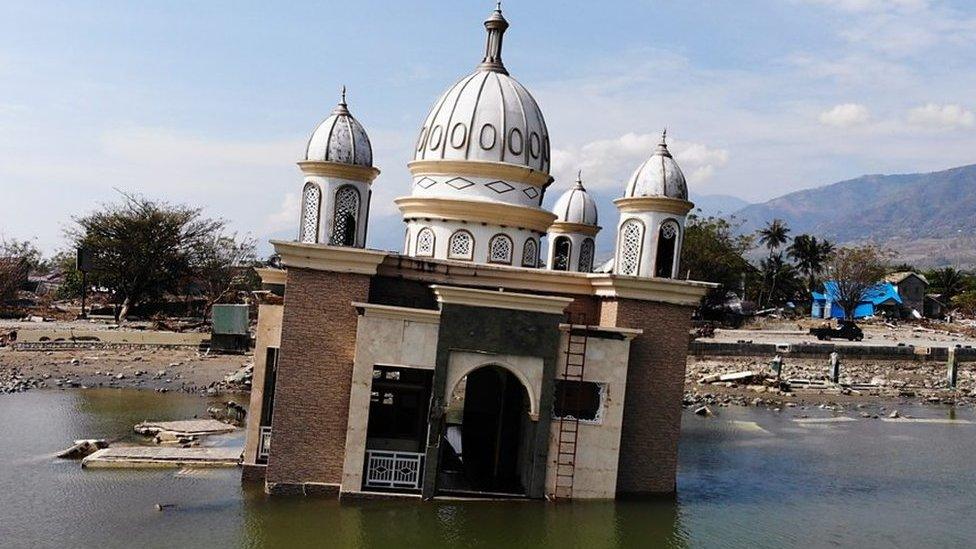

The tsunami wiped out buildings in Carita

The area will inevitably become the subject of intense scrutiny in the weeks ahead.

Landslide- or rockfall-driven tsunamis can be very big indeed. In the geological record, they have been responsible for gargantuan events.

Just recently in Greenland in 2017, a 100m (330ft) wave was produced by a rockslide entering a fjord in the west of the country; and there is still some suspicion that September's damaging tsunami that affected Sulawesi Island in Indonesia was, in part at least, strengthened by the mass movement of sediment, either entering the water from shore or slipping down underwater slopes in Palu Bay.

One of the most distressing things on occasions like this is to see video of people going about their lives completely unaware of what is about to hit them.

If there had been a major earthquake tremor associated with the eruption on Anak Krakatau, this might have been enough to prompt many locals to take evasive action.

But although there was seismicity reported by sensitive instruments, it was not large enough to register with people and change their behaviour. And people really have to rely on themselves for evacuation in cases like this because the distance from the source of the tsunami is so short.

"Tsunami warning buoys are positioned to warn of tsunamis originated by earthquakes at underwater tectonic plate boundaries. Even if there had been such a buoy right next to Anak Krakatau, this is so close to the affected shorelines that warning times would have been minimal given the high speeds at which tsunami waves travel," observed Prof Dave Rothery from the UK's Open University.

What an event like this one (and the one at Palu City which also caught the population unawares) teaches us is that there needs to be far more investigation into the hazards that exist away from the more expected dangers in the region.

Relatives are desperate to find their loved ones alive

Enormous research effort has gone into understanding what are called subduction earthquakes and tsunamis, such as the 2004 disaster which originated on the Sunda Trench, where one tectonic plate dives under another. The science now needs to encompass more of the wider threats in the region.

This recognition was voiced strongly at this month's American Geophysical Union Meeting - the world's largest annual gathering of Earth scientists.

"Focus is always where the light is," Prof Hermann Fritz, from the Georgia Institute of Technology in the US, told the AGU conference.

"The focus has been on Sumatra and Java - on the big subduction trenches. The warning centres have also been focussing on that - because we've had big events such as Japan [2011], Chile in 2010 and Sumatra in 2004. These are all classic subduction zone events, so everything has been geared towards that - the science from the scientists and also the warnings from warning centres."

This page was initially published on Saturday and has been updated to reflect new information, in particular from Europe's Sentinel satellite system.

- Published23 December 2018

- Published23 December 2018

- Published7 October 2018

- Published23 December 2018