New Horizons: Nasa waits for signal from Ultima Thule probe

- Published

Where is Ultima Thule? BBC Science Editor David Shukman explains

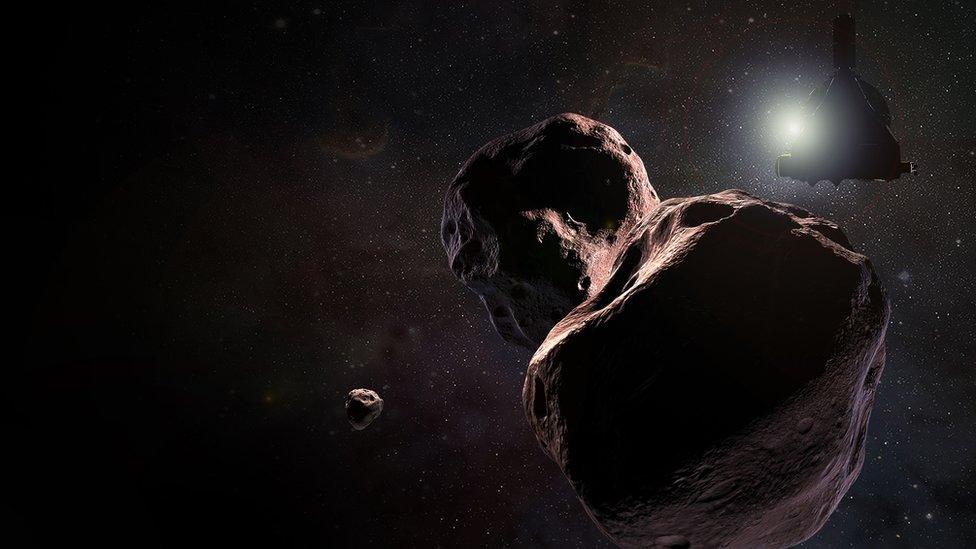

The American space agency is waiting for a signal from its New Horizons probe to confirm that it has made a successful flyby of Ultima Thule.

The craft should have hurtled by the 30km-wide icy object earlier on Tuesday, acquiring a swathe of pictures and other scientific measurements.

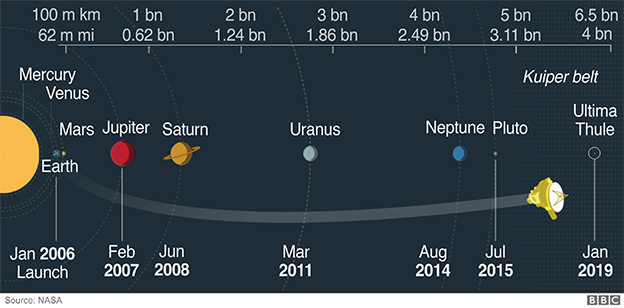

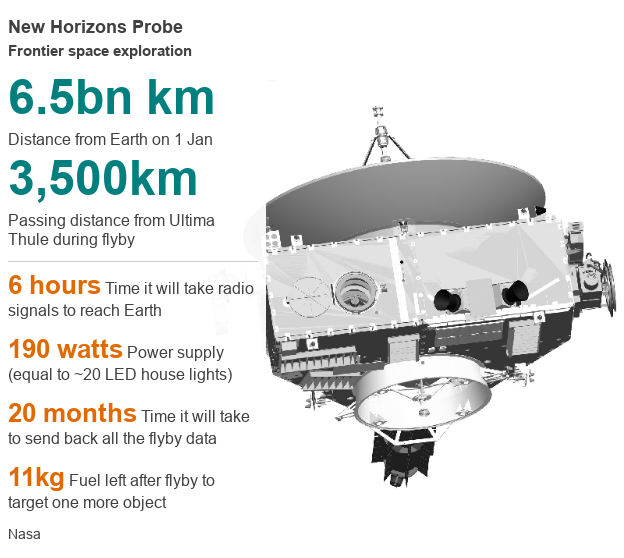

At 6.5 billion km from Earth, the encounter is the most distant ever exploration of a Solar System body.

The "phone home" message should be picked up by Nasa around 15:30 GMT.

It is expected to tell controllers that New Horizons is healthy and that its memory banks are full of data.

Some choice pictures will then be downlinked for public release, most probably on Wednesday.

Ultima is in what's termed the Kuiper belt - the band of frozen material that orbits the Sun more than 2 billion km (1.25bn miles) further out than the eighth of the classical planets, Neptune; and 1.5 billion km beyond even the dwarf planet Pluto, which New Horizons visited in 2015.

It's estimated there are hundreds of thousands of Kuiper members like Ultima, and their frigid state almost certainly holds clues to the formation conditions of the Solar System 4.6 billion years ago.

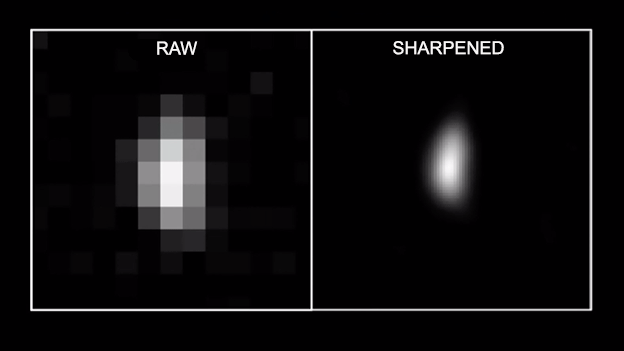

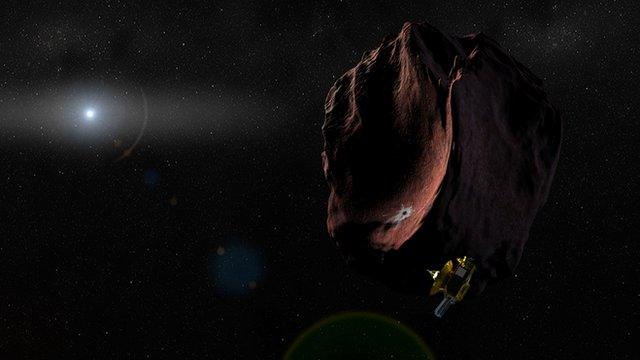

Ultima appears elongated: One of the last pictures returned to Earth before the flyby

"Go New Horizons!" enthused chief scientist Alan Stern at 05:33 GMT, the moment when the spacecraft would have been at its closest point to Ultima Thule in the flyby sequence.

"Never before has a spacecraft explored something so far away."

Earlier, he said: "I'd be kidding you though if I didn't tell you that we're also on pins and needles to see how this turns out.

"We only get one shot at it. Nothing like this has ever been done before, and with any enterprise like this - there comes risk," he told reporters.

The risk is that New Horizons runs into fragments of ice or rock in the vicinity of Ultima.

With the spacecraft moving at 14km/s, even particles the size of a grain of rice would shred its interior components.

New Horizons was programmed to get as close as 3,500km to Ultima's surface, and to observe its rotation, geology, composition and environment.

Scientists want to know in particular how such far-off worlds were assembled. One idea is that they grew from the mass accretion of a blizzard of pebble-sized icy grains. This could say something about how all planetary bodies came into being at the start of the Solar System some 4.6 billion years ago - including the Earth.

But the researchers will have to be patient. Because of the great separation between the New Horizons and Earth, transmissions take over six hours to arrive home.

The data rates from New Horizons' 15-watt transmitter are also glacial as a consequence. Information trickles into Nasa's big antenna network at a maximum of 1,000 bits per second.

Brian May: "I want to merge the science with the music to contribute to the whole experience"

New Horizons has had its long-range camera trained on the object since August. But only on the eve of closest approach did Ultima really start to make an impression in images.

Mission scientist John Spencer presented a picture acquired on Sunday from a distance of 1.9 million km. It represented at that moment the best ever view of Ultima.

"It's a blob, only a couple of pixels across," he said. "But you can see from that blob that it's an elongated blob; it's not round. And so we're already seeing there is some interesting shape to this thing."

Children invited to mission control celebrate the moment of closest approach

When the pictures taken at closest approach are returned, they should achieve a best resolution of about 33m per pixel - more than sufficient to trace different features on Ultima's surface.

Mission control for the project is based at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Maryland. It got a sprinkle of celebrity stardust on Monday with the appearance of Queen guitarist Brian May.

The rock legend has written a song for New Horizons, and with a PhD in astrophysics he also plans to work on some of the probe's images.

"[New Horizons at Ultima Thule] touches me because it's very emblematic in my mind of the human spirit having a need and a desire to reach out," he told BBC News. "To me the song is about that quality in human beings that makes them question and makes them want to understand the Universe they live in."

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

The BBC's Sky At Night programme will broadcast a special episode on the flyby on Sunday 13 January on BBC Four at 22:30 GMT. Presenter Chris Lintott, external will review the event and discuss some of the new science to emerge from the encounter with the New Horizons team.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published18 December 2018

- Published9 May 2018

- Published12 December 2017

- Published30 August 2015

- Published10 July 2015