New Horizons: Agonising wait for news from Ultima Thule

- Published

Guests at mission control in Maryland celebrated as the news was announced

I suspect it's not that unusual to wake on New Year's Day still wondering about what happened the night before, but it's not exactly what you'd expect the team behind a Nasa spacecraft gathered at mission control to do.

Nonetheless, that's the story of two very different celebrations that happened here at Maryland's Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (JHUAPL) over the last day or so.

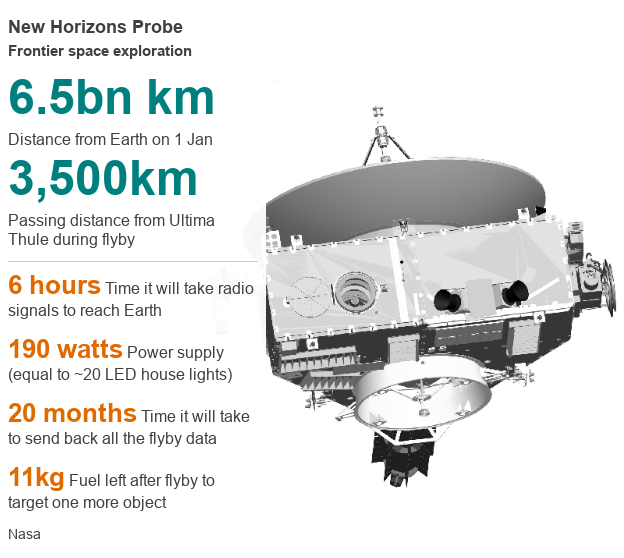

I'm writing this from the heart of the New Horizons mission, which just after midnight local time last night flew just 3,500 kilometres away from the icy surface of a rock nicknamed Ultima Thule.

There was a bit of a party here last night, and accompanying the team at mission control was everyone from scientific celebrities - Walter Alvarez, discoverer of the K-Pg boundary (formerly known as the K-T boundary) that provided evidence of the asteroid impact that did for the dinosaurs - to, well, actual celebrities.

Dr Brian May is officially part of the New Horizons team, and drew quite a crowd to his briefing. As the countdown to the flyby reached its climax, the crowd went as crazy as any New Year crowd would as the fireworks lit up the night sky.

Brian May: "I want to merge the science with the music to contribute to the whole experience"

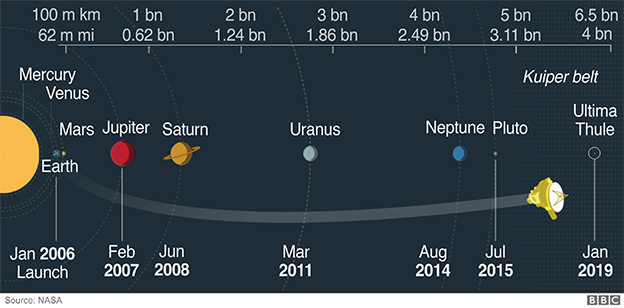

Few of those assembled slept well though, without confirmation that the spacecraft was safe. It reminded me of a similar moment in the same place in July 2015, as the world watched as New Horizons flew past Pluto.

Then, as now, the team celebrated while knowing that they had to wait to see if their plucky spacecraft had survived its encounter.

A debris detection effort preceded both encounters, but with the craft moving at 14km/s, even a collision with something the size of a pea could be fatal.

New Horizons can't talk to Earth and point to take observations at the same time, and so only after a post-flyby signal is received can the team really relax and begin to anticipate the scientific bonanza heading their way.

This morning's celebration was the real one. There was a brief delay as the mission operations manager, Alice Bowman (MOM to the team) waited for the signal from the ground station in Madrid to confirm that all is well.

Chief scientist Alan Stern (centre, back) celebrates with schoolchildren

It is - and the first decent images of Ultima Thule are likely already on their way back to Earth from the spacecraft. We'll get to see them in the next couple of days, and it will take 20 months or so to get all the data back to Earth, but as ever at big space events I'm left thinking about the human contribution to these robotic missions.

Some of the New Horizons team have been working on the mission since the early 1990s, and others will have careers that depend on a successful return of data from this flyby.

All are anticipating a couple of sleepless nights as they struggle to make sense of a world that until now has been visible only as a couple of pixels.

Scattered amongst the crowd are those who will carry on New Horizons' legacy - I've spotted team members from Nasa's Osiris-ReX spacecraft which entered orbit around the asteroid Bennu yesterday, and the leaders of upcoming missions to a strange metal asteroid called Psyche and to the trojan asteroids that share an orbit with Jupiter.

Wherever we've explored in the Solar System, we've found the unexpected. As we wait for our close up look at Ultima Thule, it's hard not to get excited about what happens next.

The BBC's Sky At Night programme will broadcast a special episode on the flyby on Sunday 13 January on BBC Four at 22:30 GMT. Presenter Chris Lintott, external will review the event and discuss some of the new science to emerge from the encounter with the New Horizons team.