New Horizons: Nasa probe survives flyby of Ultima Thule

- Published

- comments

Alan Stern and Alice Bowman celebrate the arrival of New Horizons' signal

The US space agency's New Horizons probe has made contact with Earth to confirm its successful flyby of the icy world known as Ultima Thule.

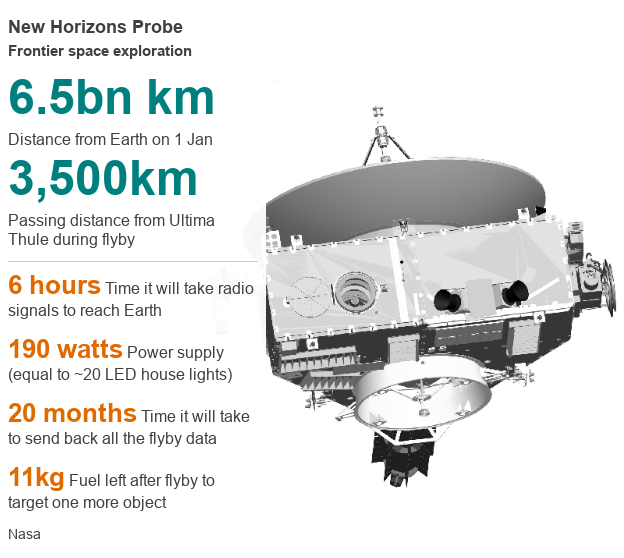

The encounter occurred some 6.5bn km (4bn miles) away, making it the most distant ever exploration of an object in our Solar System.

New Horizons, external acquired gigabytes of photos and other observations during the pass.

It will now send these home over the coming months.

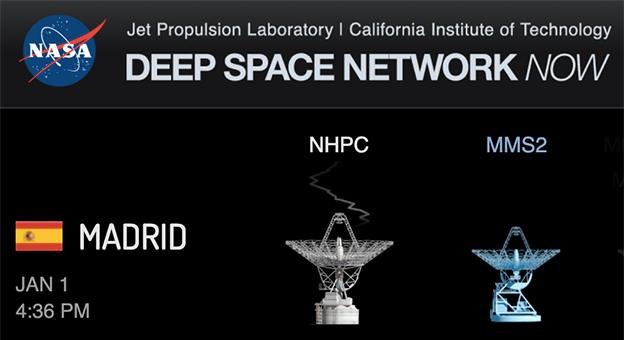

The radio message from the robotic craft was picked up by one of Nasa's big antennas, in Madrid, Spain.

It had taken fully six hours and eight minutes to traverse the great expanse of space between Ultima and Earth.

A good, clear signal was picked up by the radio antenna system in Spain

Controllers at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Maryland greeted the reception of the signal with cheers and applause.

"We have a healthy spacecraft," announced Mission Operations Manager Alice Bowman. "We've just accomplished the most distant flyby."

This first radio message contained only engineering information on the status of the spacecraft, but it included confirmation that New Horizons executed its autonomous flyby observations as instructed and that the probe's onboard memory was full.

A later downlink on Tuesday will see some choice images returned to give scientists and the public a taster of what New Horizons saw through its cameras.

If there is one note of caution it is that the timing and orientation of the spacecraft had to be spot on if the probe was not to shoot pictures of empty space! As a result, there will continue to be some anxiety until the data can be examined.

"The highest resolution images taken at closest approach required perfect pointing, almost," said Project Scientist Hal Weaver. "We think, based on everything we've seen so far, that was achieved."

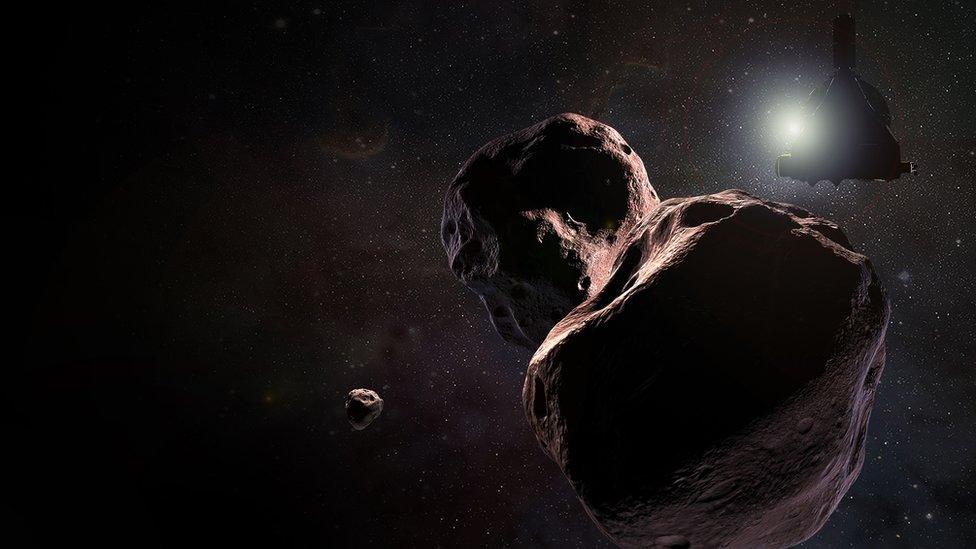

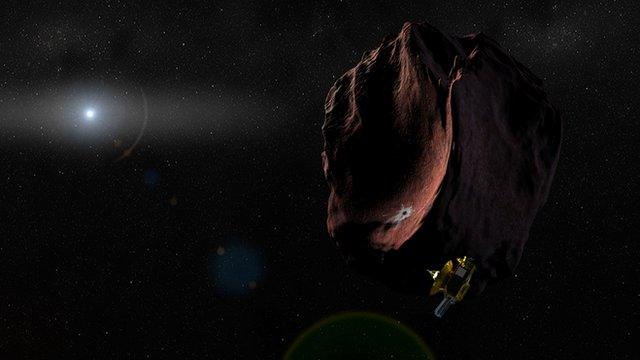

Taken from a few hundred thousand km: A last image on approach to the target

Other stories on the BBC you might like:

Ultima is in what's termed the Kuiper belt - the band of frozen material that orbits the Sun more than 2 billion km further out than the eighth of the classical planets, Neptune; and 1.5 billion km beyond even the dwarf planet Pluto which New Horizons visited in 2015.

It's estimated there are hundreds of thousands of Kuiper members like Ultima, and their frigid state almost certainly holds clues to the formation conditions of the Solar System 4.6 billion years ago.

The vast separation between New Horizons and Earth, coupled with the probe's small, 15-watt transmitter, mean data rates are glacial, however.

They top out at 1 kilobit per second. To retrieve all of the imagery stored on the probe is therefore expected to take until September 2020.

The first of the very highest resolution pictures should come down to Earth in February. But this wouldn't delay the science, said Principal Investigator Alan Stern.

"The [lower resolution] images that come down this week will already reveal the basic geology and structure of Ultima for us, and we're going to start writing our first scientific paper next week," he told reporters.

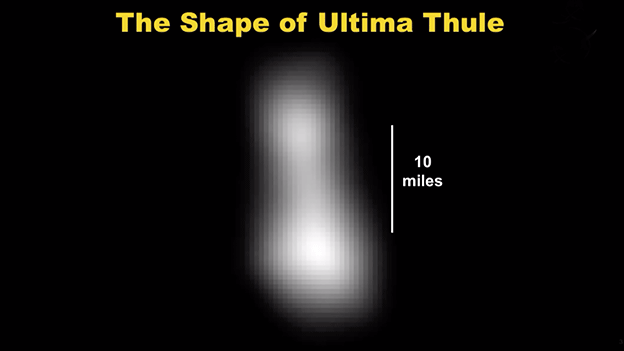

Even just the final picture released from the approach phase to the flyby contained tantalising information. Ultima appears in it as just a blob, but immediately it has allowed researchers to refine their estimate of the object's size - about 35km by 15km.

What's so special about the Kuiper belt?

Several factors make Ultima Thule, and the domain in which it moves, so interesting to scientists.

One is that the Sun is so dim in this region that temperatures are down near 30-40 degrees above absolute zero. As a result, chemical reactions have essentially stalled. This means Ultima is in such a deep freeze that it is probably perfectly preserved in the state in which it formed.

Another factor is that Ultima is small (about 30km across), and this means it doesn't have the type of "geological engine" that in larger objects will rework their composition.

And a third factor is just the nature of the environment. It's very sedate in the Kuiper belt.

Unlike in the inner Solar System, there are probably very few collisions between objects. The Kuiper belt hasn't been stirred up.

Alan Stern said: "Everything that we're going to learn about Ultima - from its composition to its geology, to how it was originally assembled, whether it has satellites and an atmosphere, and that kind of thing - is going to teach us about the original formation conditions in the Solar System that all the other objects we've gone out and orbited, flown by and landed on can't tell us because they're either large and evolve, or they are warm. Ultima is unique."

What does New Horizons do next?

First, the scientists must work on the Ultima data, but they will also ask Nasa to fund a further extension to the mission.

The hope is that the course of the spacecraft can be altered slightly to visit at least one more Kuiper belt object sometime in the next decade.

New Horizons should have just enough fuel reserves to be able to do this. Critically, it should also have sufficient electrical reserves to keep operating its instruments into the 2030s.

The longevity of New Horizon's plutonium battery may even allow it to record its exit from the Solar System.

The two 1970s Voyager missions have both now left the heliosphere - the bubble of gas blown off our Sun (one definition of the Solar System's domain). Voyager 2 only recently did it, in November.

And in case you were wondering, New Horizons will never match the Voyagers in terms of distance travelled from Earth. Although New Horizons was the fastest spacecraft ever launched in 2006, it continues to lose ground to the older missions. The reason: the Voyagers got a gravitational speed boost when they passed the outer planets. Voyager-1 is now moving at almost 17km/s; New Horizons is moving at 14km/s.

The BBC's Sky At Night programme will broadcast a special episode on the flyby on Sunday 13 January on BBC Four at 22:30 GMT. Presenter Chris Lintott, external will review the event and discuss some of the new science to emerge from the encounter with the New Horizons team.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published18 December 2018

- Published9 May 2018

- Published12 December 2017

- Published30 August 2015

- Published10 July 2015