Climate change: Is nuclear power the answer?

- Published

Nuclear is good for the environment. Nuclear is bad for the environment. Both statements are true.

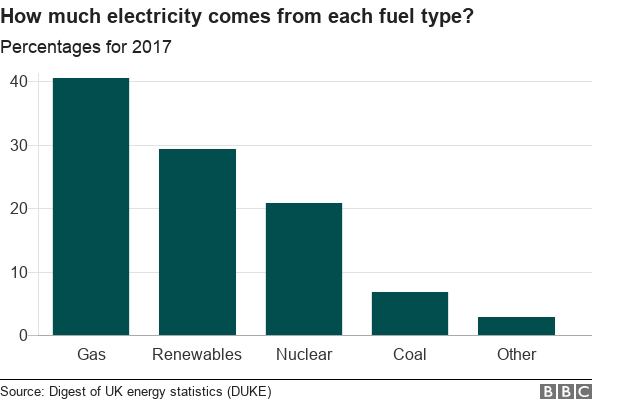

Why is it good? Nuclear power is planned to be a key part of the UK's energy mix.

The key benefit is that it helps keep the lights on while producing hardly any of the CO2 emissions that are heating the climate.

CO2 emissions come from traditional ways of creating electricity such as burning gas and coal.

And the government is expected to have halted emissions almost completely by 2050, to help curb damage to the climate.

Why is it bad for the environment?

Because major nuclear accidents are few and far between, but when they happen they create panic.

Take the Fukushima explosions in 2011, which released radioactive material into the surrounding air in Japan. Or the Chernobyl accident in 1986, which spewed radioactive material across northern Europe.

But arguably, the bigger environmental problem is what to do with nuclear waste.

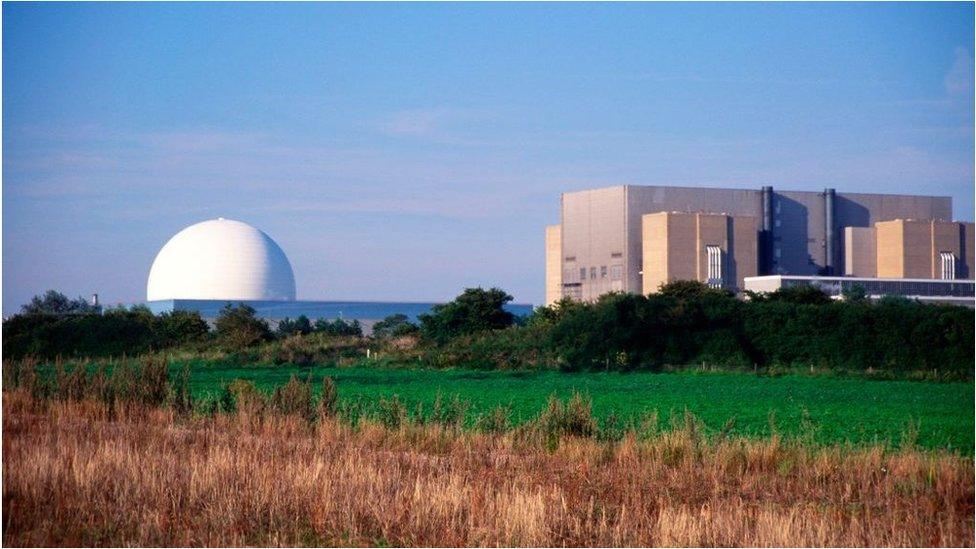

This is a very live issue in the UK, where contaminated material has been held in a temporary store at the Sellafield site in Cumbria.

The government has been trying for years to secure a site with the right geology, offering cash sweeteners to local communities to host a permanent £12bn underground store for the most dangerous waste. So far no permanent dump has been agreed - that is after 70 years of nuclear power in the UK.

Can we get by without new nuclear?

"The UK policy identifying the need for nuclear to play a role alongside renewables has been supported by numerous independent studies," said a spokesperson for EDF, which is building the Hinkley C nuclear power plant.

"Nuclear provides low-carbon electricity when the wind doesn't blow and the sun doesn't shine."

Previously civil servants estimated that future UK electricity supplies would be divided up roughly 30/30/30 between nuclear, wind and fossil fuels with carbon capture and storage (CCS).

But no-one has been willing to invest at scale in the expensive CCS technology, which pumps CO2 emissions into rocks.

Wind is ready to take its place in the sun. But with old nuclear stations closing, nuclear won't be able to fulfil its third of the deal unless new nuclear plants are built.

The issue has caused a bitter divide between environmentalists, with some arguing that the risk from climate change is so severe that it's worth supping nuclear fuel, albeit with a long spoon.

Others argue that the technology is dead and that renewables and other options can supply the UK's needs without the danger of nuclear accidents and waste.

Prof Jim Watson, director of the UK Energy Research Centre, told BBC News: "Most analysts now have accepted that we don't need 30% of energy from nuclear - renewables can take a substantially bigger share.

"But taking any option off the table makes the job of meeting essential carbon targets even harder. It would certainly be hard to do without nuclear altogether."

What are the alternatives?

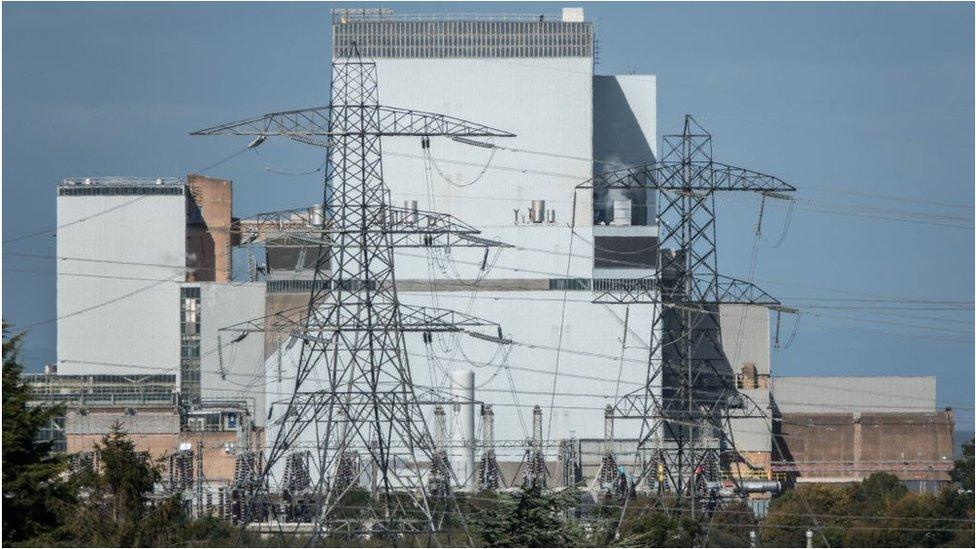

The people who keep our lights on are looking to find ways of extending the life of existing nuclear plants, and trying to get nuclear power more cheaply.

Factory-built small modular reactors that can be delivered on the back of a lorry are touted as one solution - but they are not expected to be operating at any scale until well into the 2030s. And what's more, with nuclear, bigger is generally better.

Meanwhile, other options are being urgently explored. We need the power market to be more flexible. We need to develop better batteries and other techniques for storing power.

And we need systems that will reduce the demand for electricity at peak times and transfer the demand to off-peak times when wind energy is plentiful and cheap.

One particularly hard task is to find ways of storing power between months and even seasons.

Last but by no means least, the government needs to prompt people to insulate their homes to reduce the demand for energy in the first place.

The news that Hitachi is suspending work on a nuclear plant in north Wales has made all these tasks more urgent.

Follow Roger on Twitter @rharrabin

- Published17 January 2019

- Published11 September 2017

- Published12 September 2011