Space harpoon skewers 'orbital debris'

- Published

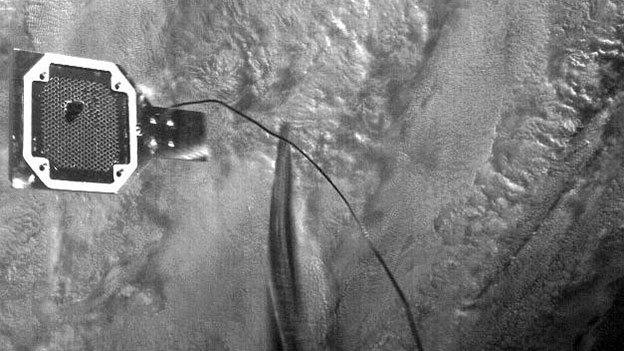

A harpoon was fired to catch some debris successfully

The British-led mission to test techniques to clear up space junk has demonstrated a harpoon in orbit.

The RemoveDebris satellite, external fired the projectile into a target board held at a distance on the end of a boom.

Video of the event shows the miniature spear fly straight and true, and with such force that it actually breaks the target structure.

But, importantly, the harpoon's barbs deploy and hold on to the board, preventing it from floating away.

Prof Guglielmo Aglietti, from the University of Surrey in Guildford, is the principal investigator on the mission. He declared the experiment a total success.

"You see the harpoon hit the target in the centre, as expected, and get embedded. The target comes off the boom, but that's not a problem because the harpoon is tethered; it's attached to a wire. So all elements worked," he told BBC News.

The £13m RemoveDebris project was launched last year to showcase ways of tackling the growing litter problem in orbit.

The target breaks off the boom when the harpoon hits home

What's the problem that needs addressing?

More than 60 years of space activity have left something like 8,000 tonnes of material wandering aimlessly around the planet.

From old rocket parts to broken fragments of spacecraft - this waste now poses a serious collision hazard to operational satellites that deliver important services, such as telecommunications and weather observations.

RemoveDebris is a 100kg satellite that carries a number of demonstration technologies that could be used in the future to snare this sky-high rubbish.

It has already shown how a net could be used to capture a piece of junk.

It has also run the rule over a novel tracking system. This vision-based navigation (VBN) technology essentially tells a hunter spacecraft how its prey is behaving - how it's moving and even tumbling.

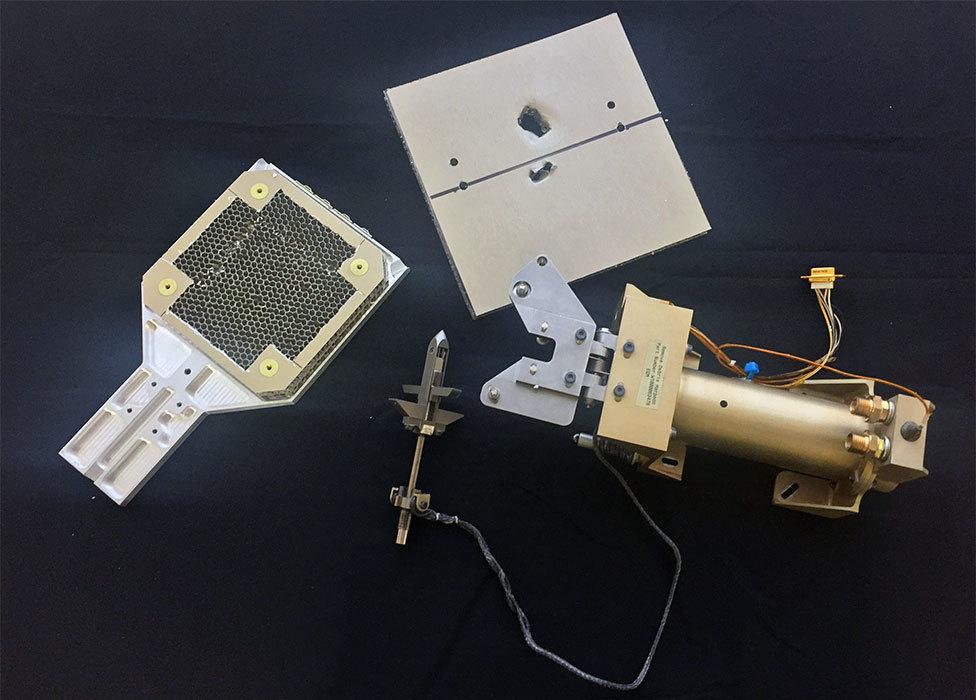

Scale: The target (left) is about 10cm along the edge

How did the harpoon experiment work?

This was the third demo of the mission.

To give a sense of scale - the extended boom is about 1.5m in length, and the target board is roughly 10cm along the edge.

The target was made from standard satellite panelling - an aluminium honeycomb structure.

The experiment was actually done "in the blind", in a part of the demo satellite's flight-path that was out of contact with controllers on the ground at Surrey Satellite Technology Ltd, also in Guildford.

This meant all commands had to be pre-loaded. There was also the added complication that the act of firing the projectile would destabilise the spacecraft; it would immediately start to rotate.

"We knew that would happen," said SSTL operator Katie Bashford.

"The spacecraft went into its expected 'safe mode' and the team on the ground was then able to successfully stop the spinning and get RemoveDebris back into the normal orientation."

Harpoons are just one possible solution to the junk issue

What happens next for RemoveDebris?

In the next few weeks, the satellite will undertake its final test - the deployment of a big membrane to accelerate its fall to Earth.

This end-of-mission "drag sail" will catch the residual air molecules at the satellite's altitude of 400km and pull it down more quickly than would normally be the case.

"It's now really up to our partners in industry as to where they take these technologies," said Prof Aglietti.

"As a university, we've given a proof of concept for the basic ideas; we've shown the technology-readiness has reached a certain level. It's now for industry to turn these concepts into a commercial product or business."

It is widely accepted that a range of technologies will be needed to tackle the junk problem.

Simon Fellowes: "To know how something will work in space we need to be in space"

Other concepts are being developed that involve robotic arms reaching out and grabbing debris. But these systems would work best only on cooperative targets.

If the junk was tumbling at speed, a net or a harpoon may be the better option.

"The space debris problem is a real problem and needs dealing with. But now that we've taken the first step in showing people that there is a viable way of handling objects, we hope that people will take that onboard and run with it," said Simon Fellowes, from the Surrey Space Centre, and who manages the consortium behind RemoveDebris.

That consortium comprises 10 partners from across Europe and South Africa. They put in half the mission cost with the other half coming from the European Commission's Horizon 2020 science budget.

Already, there are a number of commercial operations in development that would see satellites go up to latch on to ageing spacecraft to extend their lives by providing extra fuel or taking over flight control.

It would not be a major step on from this to also bring those ageing spacecraft out of orbit as a final solution.

Artwork: In the future, missions will be sent up to remove redundant spacecraft