Artificial meat: UK scientists growing 'bacon' in labs

- Published

- comments

Scientists are racing to grow meat from pigs, chickens and cattle from cells alone

British scientists have joined the race to produce meat grown in the lab rather than reared on the hoof.

Scientists at the University of Bath have grown animal cells on blades of grass, in a step towards cultured meat.

If the process can be reproduced on an industrial scale, meat lovers might one day be tucking into a slaughter-free supply of "bacon".

The researchers say the UK can move the field forward through its expertise in medicine and engineering.

Lab-based meat products are not yet on sale, though a US company, Just, has said its chicken nuggets, grown from cells taken from the feather of chicken that is still alive, will soon be in a few restaurants.

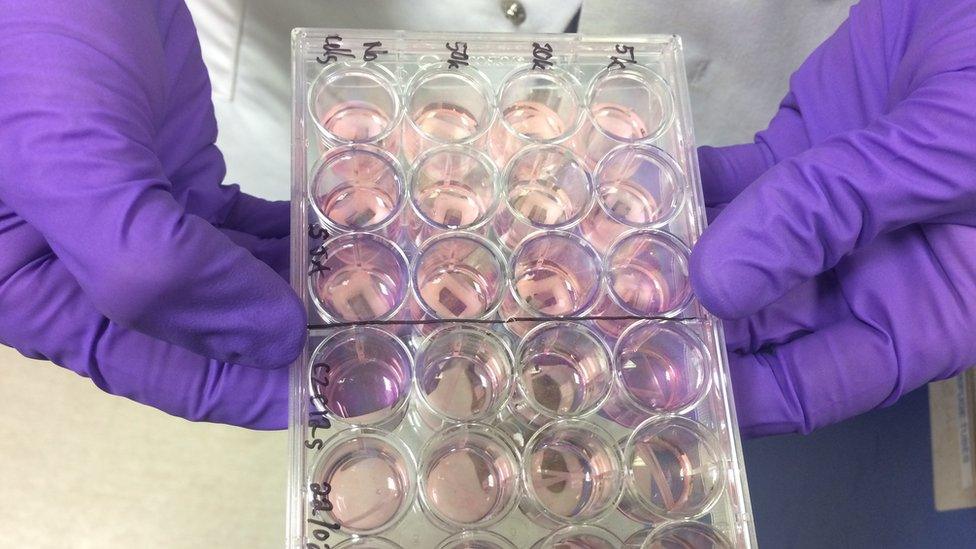

Chemical engineer Dr Marianne Ellis, of the University of Bath, sees cultured meat as "an alternative protein source to feed the world". Cultured pig cells are being grown in her laboratory, which could one day lead to bacon raised entirely off the hoof.

In the labs at Bath, the building blocks of artificial meat

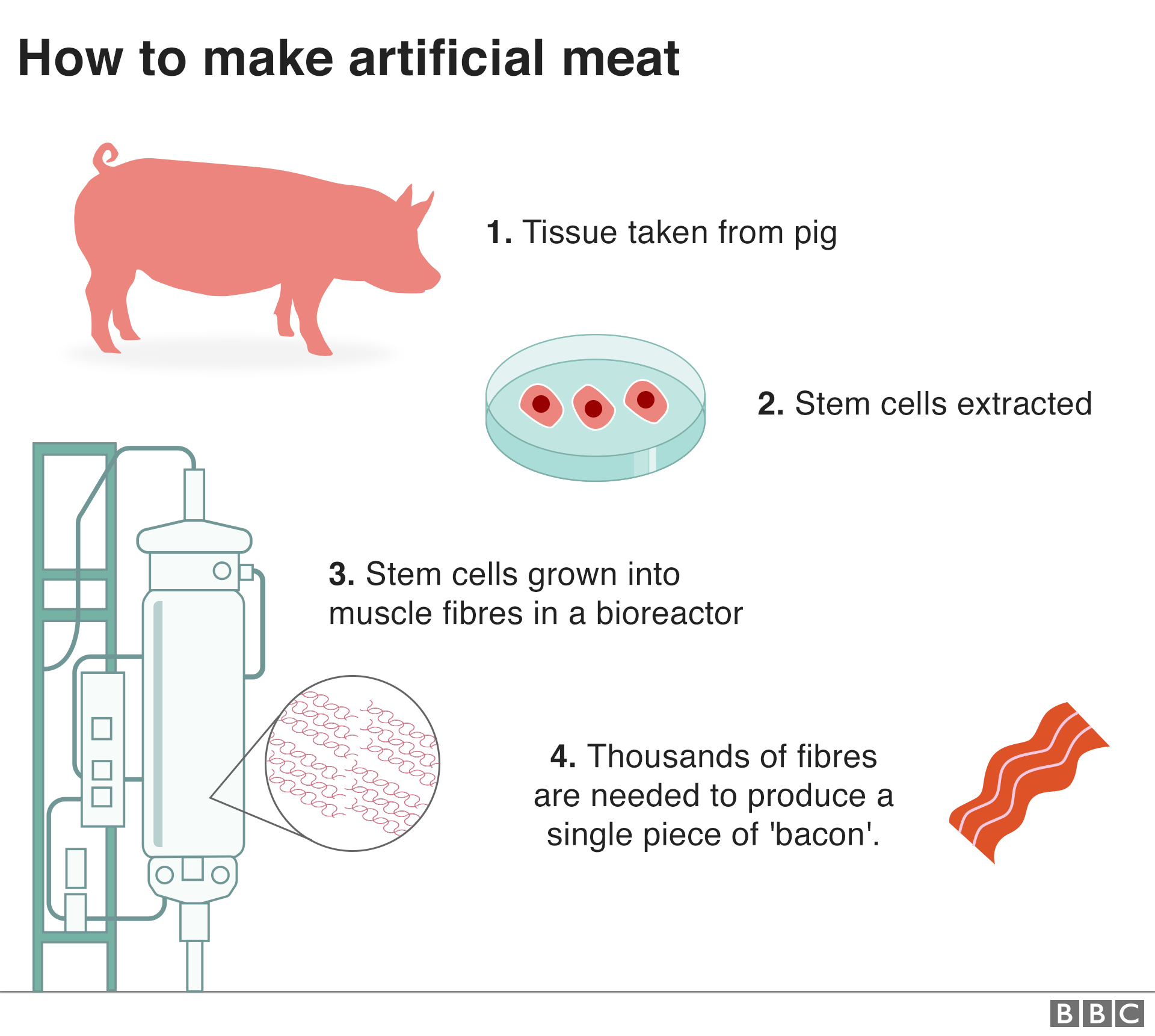

In the future, you would take a biopsy from a pig, isolate stem (master) cells, grow more cells, then put them into a bioreactor to massively expand them, says postgraduate student Nick Shorten of Aberystwyth University.

"And the pig's still alive and happy and you get lots of bacon at the end."

To replicate the taste and texture of bacon will take years of research. For structure, the cells must be grown on a scaffold.

Steps towards lab grown meat

2013: First lab-grown burger, created by a team in the Netherlands at a cost of €250,000 - largely due to the time and labour needed to turn millions of tiny cells into meat

December 2018: A "steak" grown from cells in the lab and not requiring the slaughter of a cow was produced in Israel. It cost $50 for a small thin strip, but, according to its makers, needs perfecting.

At Bath, they're experimenting with something that's entirely natural - grass. They're growing rodent cells, which are cheap and easy to use, on scaffolds of grass, as a proof of principle.

"The idea was to essentially, rather than feeding a cow grass and then us eating the meat - why don't we, in quotation marks, 'feed our cells grass'," says Scott Allan, a postgraduate student in chemical engineering.

"We use it as a scaffold for them to grow on - and we then have an edible scaffold that can be incorporated into the final product."

Dr Marianne Ellis is leading the project

The end product would be pure muscle tissue - basically, lean mince, rather than something with the taste and texture of a chop or steak, which means adding fat cells and connective cells to give it "a bit more taste".

For cultured meat to be available widely in the future, cells will need to be grown on a very large scale in a commercial facility.

"What we're doing here is looking to design bioreactors, and the bioprocess around the bioreactors, to grow muscle cells on a large scale that is economical and safe and high quality, so we can supply the muscle cells as cultured meats to as many people as want it," says Dr Ellis.

The world's first lab-grown burger was revealed in 2013 - at an eye-watering cost

She envisages taking "primary cells" from a living or recently slaughtered animal, or using a population of "immortalised" cells, that will keep on dividing. "Which means that you don't kill any animals; you have this immortal cell that can be used forever."

Slaughter-free meat is clearly a big selling point. Cultured meat might also be of interest to meat lovers who are concerned about the environmental problems that come with livestock production.

Richard Parr is managing director for Europe of The Good Food Institute, a non-profit group that promotes alternatives to the products of conventional agriculture.

He says cell-based meat has the potential to use much less land and water, produce less carbon dioxide, spare billions of animals from immense pain and suffering, and help fight anti-microbial resistance and food contamination.

"It's also a massive commercial opportunity, which companies, universities and governments should seize the opportunity to support and invest in," he argues.

You can reduce your carbon foodprint by cutting down on red meats such as beef and lamb.

According to Marianne Ellis, most analysis seems to suggest a significant reduction in greenhouse gases, land use and water use for cultured meat, while the implications for energy use are less clear.

One recent study found lab-grown meat could actually be worse for the climate than conventional meat - although the research did not look at water and land use.

"Cultured meat might be one of these promising alternatives to reduce agricultural emissions but until we get more production data we can't automatically assume that for the time being," says the author of the paper, John Lynch of the University of Oxford.

The researchers at Bath see a future where cultured meat exists alongside traditional agriculture.

Illtud Dunsford, co-founder with Marianne Ellis of the biotech start-up Cellular Agriculture, comes from a long line of farmers in Wales and is an advocate of traditional agriculture, but says there will be a need in the future to manage farmland for nature, with cattle playing a role, albeit in much smaller numbers.

"In my little farm in West Wales, ideally what I'd like to see is that we kept a range of very, very traditional native breeds of livestock on a very, very small scale to an exceptionally high welfare standard.

"The by-product from their use as a land management tool - whether that's in clearing land or restoring grasslands - would be the harvesting of cells for the culturing of cell-based meats."

Illtud Dunsford is both a farmer and a biotech entrepreneur

Lab-grown meat is not expected to be available widely for at least five years. It remains to be seen whether people will want to eat it, but surveys in the UK suggest 20% would eat it, 40% wouldn't and the rest are undecided, with younger generations, urbanites and wealthier people more open to the idea.

Chris Bryant, a psychologist at the University of Bath, says the three major concerns are to do with price, taste, and naturalness and the related issue of safety.

The third is most difficult to address, he says, based on "the naturalistic fallacy", where people reason that natural things are good and unnatural things are bad.

Ultimately, then, it will be consumers who will be the judge of the success or failure of lab-grown meat.

Follow Helen on Twitter, external.