Brunt Ice Shelf: Big iceberg calves near UK Antarctic base

- Published

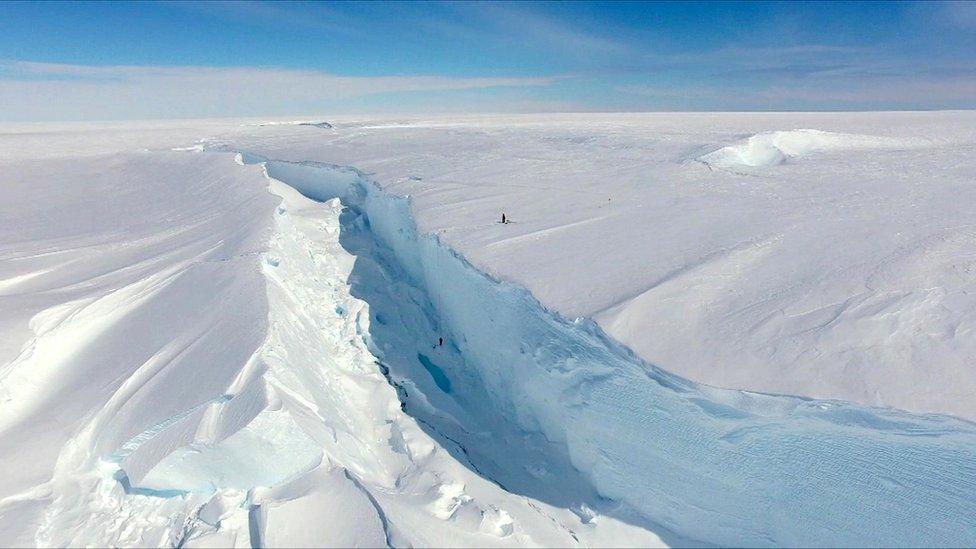

Fly along the North Rift - the crack that produced the iceberg

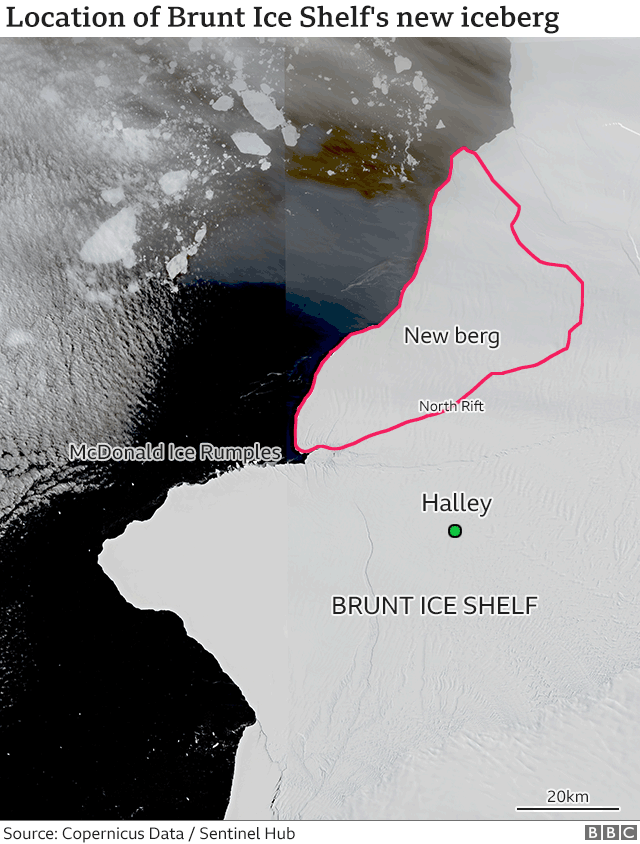

A big iceberg approaching the size of Greater London has broken away from the Antarctic, close to Britain's Halley research station.

Surface instruments on the Brunt Ice Shelf confirmed the split early on Friday.

There is currently no-one in the base, so there is no risk to human life.

The British Antarctic Survey has been operating Halley in a reduced role since 2017 because of the imminent prospect of a calving.

The berg has been measured to cover 1,270 sq km - nearly 490 square miles. Halley is positioned just over 20km from the line of rupture.

BAS has an array of GPS devices on the Brunt. These relay information about ice movements back to the agency's HQ in Cambridge.

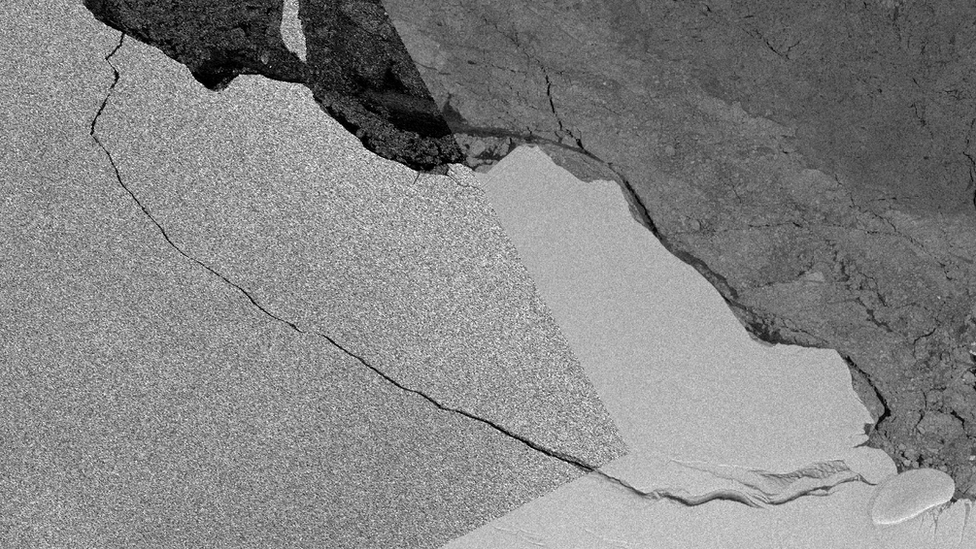

A zoomed-in portion of the image, showing the widening gap between the berg and the Brunt

Scientists will be inspecting satellite imagery as it becomes available.

They will want to see that no unexpected instabilities emerge in the remaining ice shelf platform that holds Halley.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Prof Adrian Luckman has been tracking satellite images of the Brunt in recent weeks and predicted the calving.

"Although the breaking off of large parts of Antarctic ice shelves is an entirely normal part of how they work, large calving events such as the one detected at the Brunt Ice Shelf on Friday remain quite rare and exciting," the Swansea University remote-sensing expert said.

"With three long rifts actively developing on the Brunt Ice Shelf system over the last five years, we have all been anticipating that something spectacular was going to happen.

"Time will tell whether this calving will trigger more pieces to break off in the coming days and weeks. At Swansea University we study the development of ice shelf rifts because, while some lead to large calving events, others do not, and the reasons for this may explain why large ice shelves exist at all," he told BBC News.

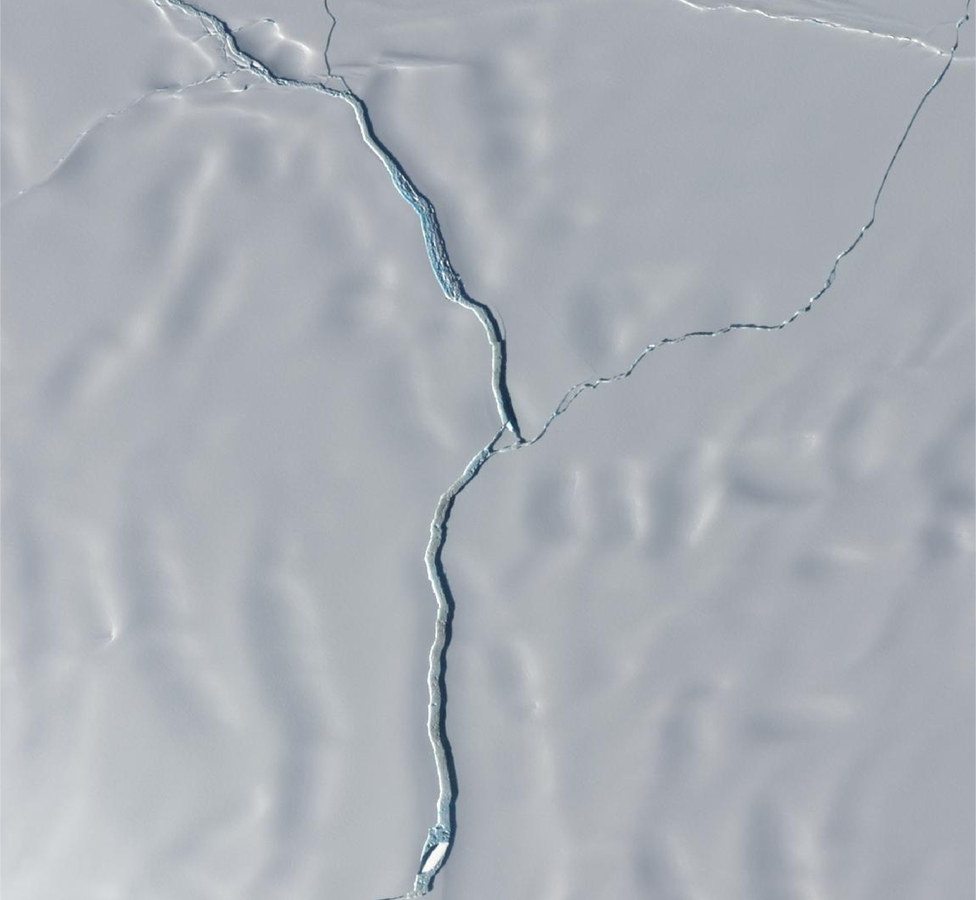

A cloudless satellite view from early February shows the approximate berg area

Where exactly is this?

It is on the Brunt Ice Shelf, which is the floating protrusion of glaciers that have flowed off the land into the Weddell Sea. On a map, the Weddell Sea is that sector of Antarctica directly to the south of the Atlantic Ocean. The Brunt is on the eastern side of the sea. Like all ice shelves, it will periodically calve icebergs. The last major chunk to have come off in this area was in the early 1970s.

Halley Station is famous for its research on the ozone layer

Was this breakaway anticipated?

Absolutely. Scientists continuously monitor any major cracks in the Brunt, and have been following the propagation of quite a few in recent years. Indeed, it was an acceleration in the movement of these fissures that actually prompted BAS to relocate Halley "upstream" in the flow of ice in 2016/17. All the major cracks converge on a location known as the McDonald Ice Rumples. This is a pinning point - a section of shallow sea floor - that the Brunt must grind past. One particular crack, called the North Rift, spread out from the rumples to draw the outline of the berg that has now calved.

Friday's Sentinel-2 satellite image reveals clear blue water in the North Rift

Just how big is the new berg?

Estimates put it at around 1,270 sq km. Greater London is about 1,500 sq km; the Welsh county of Monmouthshire is roughly 1,300 sq km. That's big by any measure, although not as large as the monster A68 berg which calved in July 2017 from the Larsen C Ice Shelf on the western side of the Weddell Sea. But even at a quarter of the size of A68, the Brunt block will need to be tracked because of the future risk it could pose to shipping. The US National Ice Center will give the new berg a designation in due course. Because it is in the same Antarctic quadrant (0-90W) as A68's origin, the Brunt berg will also carry the letter "A" in its name. It's likely to be called A74.

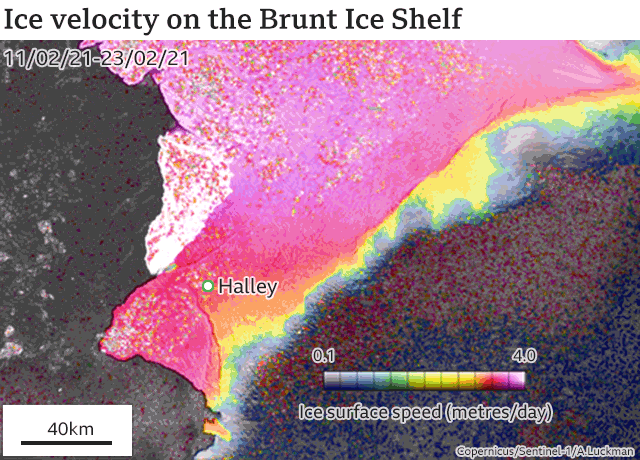

Scientists knew the berg was coming because the ice had speeded up

BAS director Dame Jane Francis commented: "Our teams at BAS have been prepared for the calving of an iceberg from the Brunt Ice Shelf for years. We monitor the ice shelf daily using an automated network of high-precision GPS instruments that surround the station, these measure how the ice shelf is deforming and moving. We also use satellite images from the European Space Agency, Nasa and the German satellite TerraSar-X.

"All the data are sent back to Cambridge for analysis, so we know what's happening even in the Antarctic winter, when there are no staff on the station and it's pitch black."

Is this climate change in action?

No. The calving of bergs at the forward edge of an ice shelf is a very natural behaviour. A shelf will maintain an equilibrium and the ejection of bergs is one way it balances the accumulation of mass from snowfall and the input of more ice from the feeding glaciers on land. Unlike on the Antarctic Peninsula on the other side of the Weddell Sea, scientists have not detected climate changes in the Brunt region that would significantly alter the natural process described above. What is more - estimates suggest the Brunt was at its biggest extent in at least 100 years before the calving. The event was overdue.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published12 July 2017

- Published13 January 2017

- Published2 February 2017

- Published4 May 2016