UK's Sabre space plane engine tech in new milestone

- Published

- comments

Mark Thomas: "We subjected the technology to the temperature 'threat' of high speed"

UK engineers developing a novel propulsion system say their technology has passed another key milestone.

The Sabre air-breathing rocket engine is designed to drive space planes to orbit and take airliners around the world in just a few hours.

To work, it needs to manage very high temperature airflows, and the team at Reaction Engines Ltd, external has developed a heat-exchanger for the purpose.

This key element has just demonstrated an impressive level of performance.

It has shown the ability to handle the simulated conditions of flying at more than three times the speed of sound.

It did this by successfully quenching a 420C stream of gases in less than 1/20th of a second.

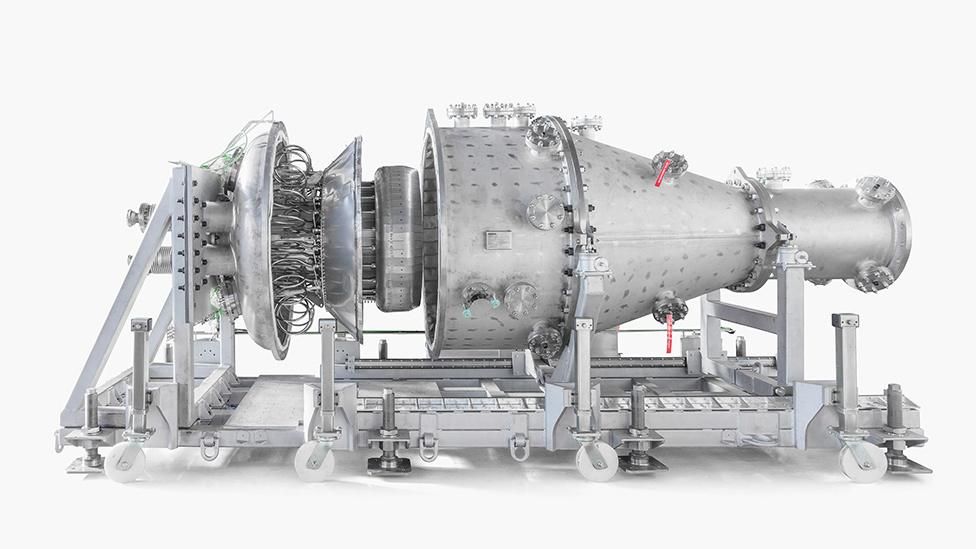

Artwork: In the test set-up, the pre-cooler is fed by the exhaust gases from a military jet engine

The REL group is confident its "pre-cooler" technology can now go on to show the same performance in conditions that simulate flying above five times the speed of sound, or Mach 5.

That would mean rapidly dumping the energy in a 1,000-degree airflow.

"We're now able to prove many of the claims we've been making as a business, backed up by very high-quality data," REL's CEO Mark Thomas told BBC News.

"In this most recent experiment, we've near-instantaneously transferred 1.5 Megawatts of heat energy - the equivalent of 1,000 homes' worth of heat energy."

The testing was conducted at a dedicated facility at the Colorado Air and Space Port in the US.

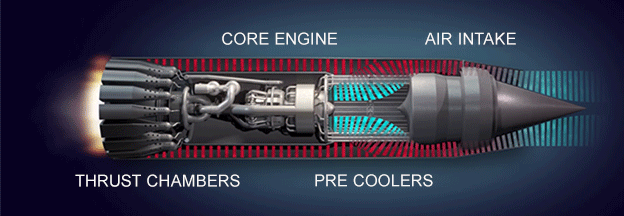

Without the pre-cooler tech at the front, Sabre would struggle in the expected temperature regime

Sabre can be thought of as a cross between a jet engine and a rocket engine.

At slow speeds and at low altitude, it would behave like a jet, burning its fuel in a stream of air scooped from the atmosphere.

At high speeds and at high altitude, it would then transition to full rocket mode, combining the fuel with a small supply of oxygen the vehicle had carried aloft.

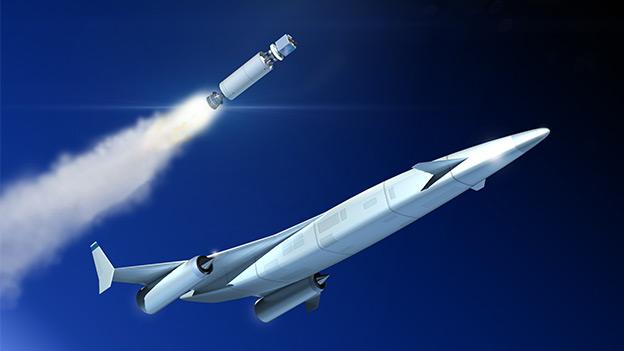

The early air-breathing approach would deliver substantial weight savings, and allow a space plane, for example, to go straight to orbit without throwing away propellant stages on the way up, as rockets do now.

But the concept brings with it an immense heat challenge.

The faster the flow of air into the engine's intake during the high-speed ascent, the higher the temperature.

And the heat would rise still further once the flow was slowed and compressed prior to entering the combustion chambers.

Such conditions would ordinarily melt the insides of the engine.

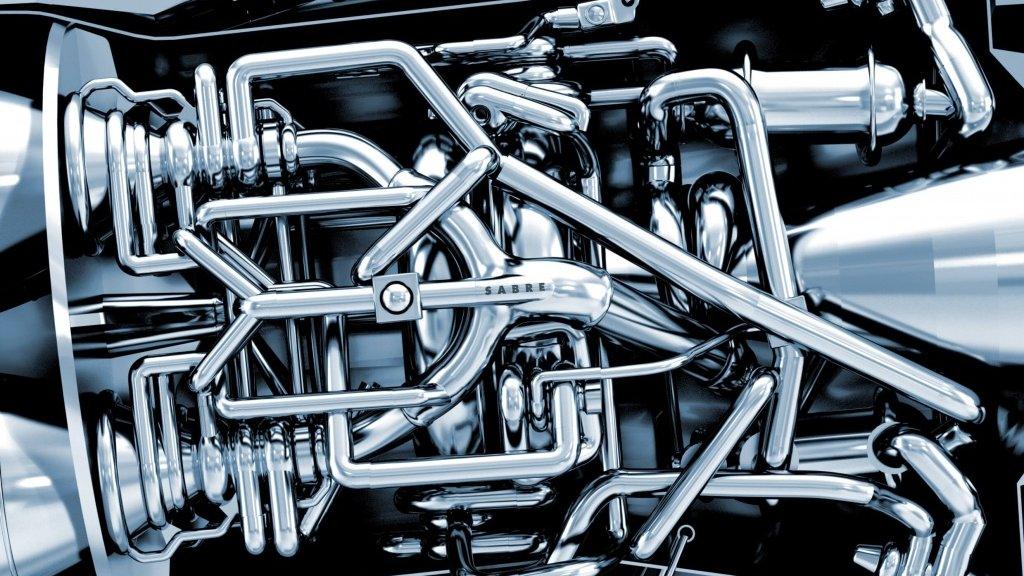

The chilled helium flowing through the pre-cooler's piping takes away the heat

Sabre's pre-cooler seeks to solve this problem by efficiently, and swiftly, extracting the heat by first passing the intake gases through a tightly packed array of fine tubing. This tubing is fed with chilled helium.

In 2012, REL put the pre-cooler in front of a viper jet engine and sucked ambient air through the heat-exchanger. The gas stream immediately dropped to minus-150C.

Now, the company has flipped the set-up, putting the jet engine from an old F-4 Phantom fighter-bomber in front of the pre-cooler to drive hot gases directly across the piping array.

The completed Colorado experiment replicates the thermal conditions corresponding to flight at Mach 3.3, the record-breaking speed at which the American SR-71 Blackbird spy plane used to operate. Importantly, though, the pre-cooler took out all the heat.

"This technology has wide application, not just in the immediate, obvious domain of high-speed flight but across the aerospace industry more generally, and into more commercial applications - anywhere there's a significant heat-management challenge and you're looking for ultra-lightweight, miniaturised, high-performance solutions," Mr Thomas said.

The Colorado tests continue. Meanwhile, back in England, REL is progressing towards a demonstration of the core part of the engine, expected to get under way next year.

This core combustion section recently passed its preliminary design review under the eye of propulsion experts at the European Space Agency. Esa has been brought in by the UK government to act as a technical auditor on the project.

The Oxfordshire company is developing Sabre with the support of BAE Systems, Rolls-Royce and Boeing. All are keen to see the many years of refinement on the engine concept finally come to fruition.

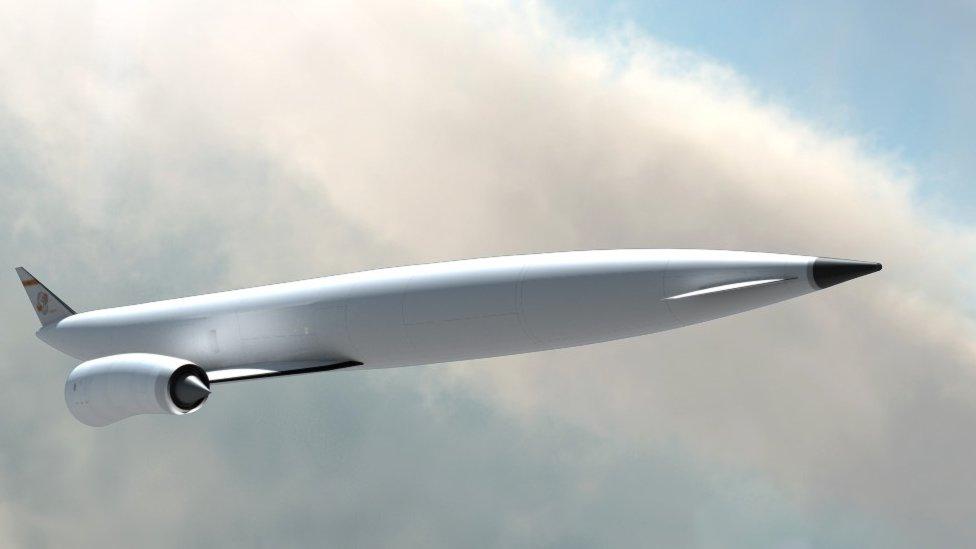

Artwork: There are many applications for this technology, but a reusable space plane would be one

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published15 March 2019

- Published12 April 2018

- Published2 November 2015

- Published9 February 2015

- Published29 May 2014

- Published16 July 2013