Climate change: Will India's election energy lead to CO2 rise?

- Published

India's CO2 emissions is predicted to roughly double by 2040

India's major political parties competing in the ongoing general elections have pledged free electricity to farmers, ambitious infrastructure projects and rapid expansion of the manufacturing sector. What impact could this have on carbon emissions in India, already the world's third largest CO2 producer?

Hundreds of lorries each day haul tens of thousands of tonnes of coal out of massive open cast mines in the Korba district, Chhatisgarh state in central India.

At night, the place illuminates with so much light that one can see plumes of smoke coming out of coal-fired power plants - just like in daylight.

This is India's major power hub, with Chhatisgarh providing almost 25% of the country's electricity.

More than 70% of it comes from coal burning, according to independent think tanks and global energy agencies. The Indian government puts the figure at below 55%.

"Coal-fired power plants have always received the government's backing," says Sunil Dahiya, clean energy and climate campaigner with Greenpeace.

"And coal demand is not going to decrease right now."

Ramping up renewables

Andhra Pradesh, the state just south of Chhatisgarh, has a solar park that until recently was the world's largest.

Solar power has seen the strongest growth among renewables

With 4.5 million solar panels installed in an area of 6,000 acres (2,430ha), the park has a capacity of 1,000 MegaWatts (MW).

There are other similar parks, and new ones are being built.

India says its renewable energy capacity reached 70 GigaWatts (GW) last year.

The country now ranks fourth in the world in wind power-based capacity and sixth in solar. The government's target is to reach 175 GW by 2022.

Coal demand in India increased by 5% in 2018

Coal dominance continues

Under the Paris climate agreement, India has committed to reduce the CO2 emission intensity of its GDP by 33-35% below 2005 levels by 2030.

The world's second largest populous country emitted 2.3bn tonnes of carbon dioxide in 2018 - a nearly 5% rise on the previous year, the International Energy Agency (IEA) says.

About 90% of India's energy still comes from fossil fuels and nearly two thirds of that from coal - the dirtiest of fossil fuels.

Nearly 70% of India's CO2 emissions come from the energy sector and more than two thirds of that is electricity generation.

The British Petroleum is forecasting that coal's share in India's power mix will increase by roughly 10% by 2040.

"Renewable energy consumption surges from 20 Mtoe (million tonnes of oil equivalent) today to 300 Mtoe by 2040 - concentrated mainly in the power sector and driven largely by growth in solar capacity," the BP says.

"Yet despite this growth in renewables, coal continues to dominate India's power generation mix, accounting for 80% of output by 2040."

Cement and steel - 'real challenges'

Some energy experts believe election promises could lead to more coal-burning and increased emissions.

"On one hand, the country is so aggressive on renewables, on the other hand, political parties are promising free electricity to farmers," says Srinivas Krishnaswamy, chief executive officer of Vasudha, an NGO that works in the area of energy and climate policies.

"That makes me doubt that the country's dependence on coal is going to go away."

Since the middle of this decade, India has said it will double coal production to one billion tonnes by 2020. This is on top of what India imports from countries like Australia and Indonesia.

The import increased to nearly 210m tonnes in 2018 from 190m tonnes the year before.

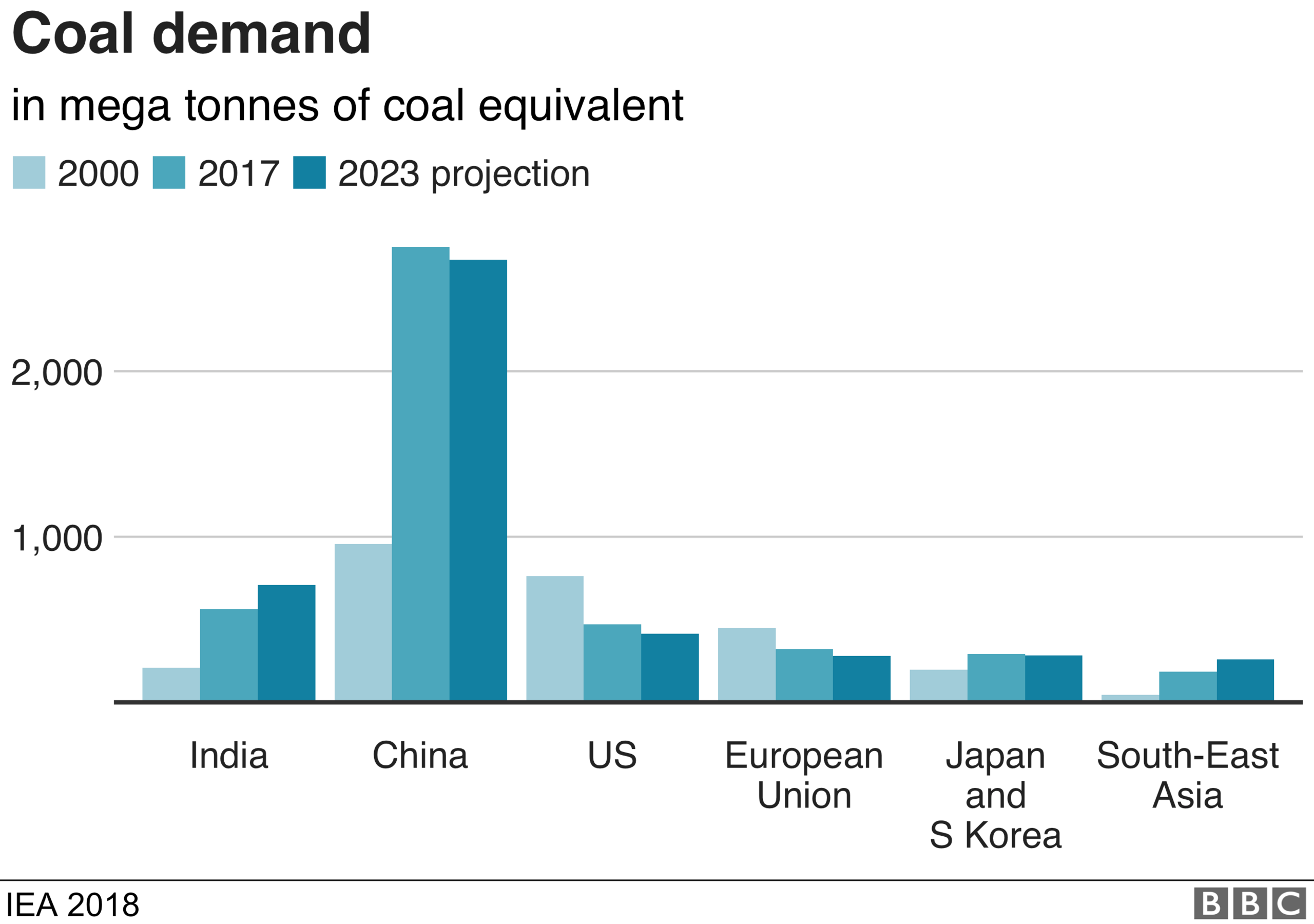

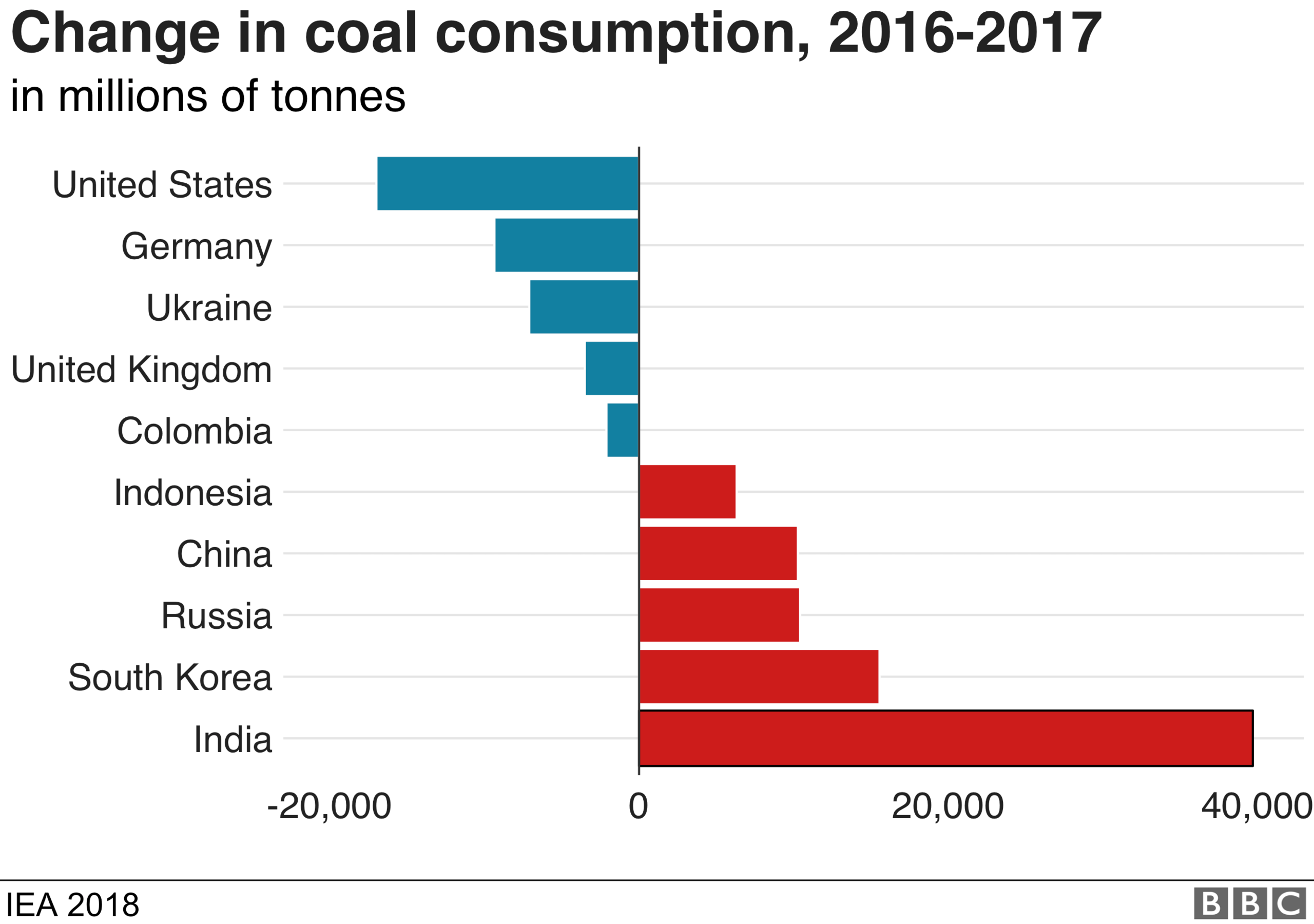

The IEA said recently coal demand had increased in India by 5% last year - just when it was decreasing in many countries.

In its earlier report, the agency projected electricity demand to triple in 2018-40.

+ 823%Solar energy

+ 66%Wind energy

And it is not just about electricity generating plants.

Steel and cement are massively energy intensive industries that are major source of emissions.

India aims to triple its cement production in the next 10 years.

In 2018, the country became the second largest producer of steel surpassing Japan.

"For emissions, cement and steel are the real challenge, and nobody seems to be talking about it," says Ajay Mathur, head of the Energy Resources Institute, an independent Delhi-based think tank.

"In the absence of technology, these are massive sources of emissions, and they are a huge issue for all the countries around the world."

Un-used electricity

But if you look at the demand-supply situation, India already has surplus electricity.

Congestion in transmission and distribution networks have caused bottlenecks in power evacuation from generation plants

It has an installed capacity of nearly 350,000MW while, officials say. Meanwhile, the demand has never crossed 180,000MW.

The bottlenecks in the country's transmission and distribution networks have been blamed.

"Lack of investment in transmission and distribution infrastructure has resulted in congestion of the network in India, impeding the evacuation of power and the development of a competitive market," the World Bank says in its report.

That is one of the reasons why most of the power plants in the country are operating a little above 50% of their capacity, known as Plant Load Factor.

Share of world's total

From 7%at present

To 14%by 2040

Some experts fear if electricity cannot be fully evacuated from existing power plants in distant places, then states could start having their own plants.

Two major coal-fired power plants have recently been approved in Bihar and Uttar Pradesh.

"Political competition between parties can create that situation, particularly if this election results into a grand coalition government," says Mr Krishnaswamy.

"But that competition could also result in installation of solar plants. But again will the renewables be able to supply the amount of energy they are now promising?"

India wants to double its coal production to 1bn tonne by 2020

Renewables pricing

Some say that now looks increasingly possible because renewable energy in India is becoming much cheaper than electricity produced from coal burning.

"The move towards renewable electricity will keep on happening because we see that as being the most cost effective way to meet people's needs," says Mr Mathur.

"Our action is not based on environmental aspirations, it is based on hard economic realities."

Renewables can generate only when there is the Sun and wind - but India's peak demand time is before midnight.

Battery technologies to store renewable energy cannot yet be source of stable electricity supply.

"For stable power generation, coal is our necessity and our plants will need more coal," says Shailendra Shukla, head of the power generation company in Chattisgarh.

"The day an alternative is available, we will stop using coal."

But even with so much of coal burning, the Indian government says it is already on its way to meet its commitments under the Paris deal.

Increasing number of consumers are switching to renewables because they are cheaper

Low per capita emissions

"India has been one of the top performers in terms of living up to climate commitments," says Mr Krishnaswamy.

"But is that adequate? Particularly because now we need to limit global warming to 1.5C degrees compared with pre-industrial period."

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) last year brought out a special report indicating that the Paris agreement's goal of limiting warming to "well below 2C degrees" could still be inadequate to fight climate change.

The BP is predicting that India will account "for more than a quarter of net global primary energy demand growth between 2017-2040".

The company adds that "42% of this new energy demand is met through coal, meaning CO2 emissions roughly double by 2040".

Chandra Bhusan, from the Centre of Science and Environment, a Delhi-based think tank, agrees that India's emissions will increase.

But he adds: "It will happen simply because we have a very low per capita emissions.

"Just for comparison, the per capita emissions from just food consumption in the UK is higher that total per capital emissions in India."

- Published2 October 2015

- Published27 November 2018

- Published14 January 2020

- Published10 April 2019

- Published10 March