European Space Agency probe to intercept a comet

- Published

Artwork: There may be little warning of a very distant visitor

The European Space Agency is to launch another mission to a comet.

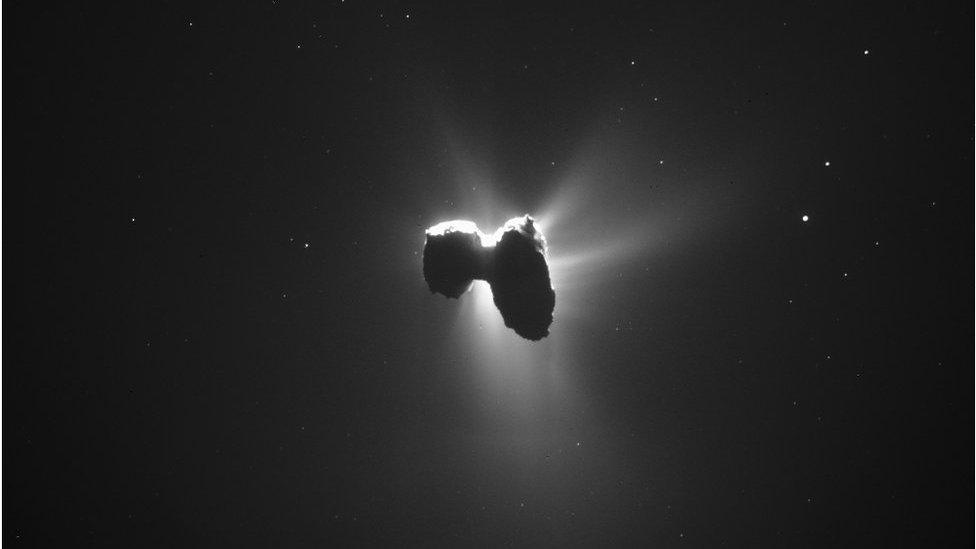

After the hugely successful Rosetta encounter with the icy dirt-ball known as 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko in 2014, officials have now selected a new venture that will launch in 2028.

It's called Comet Interceptor and will aim to catch and study an object that has come in towards the Sun from the outer reaches of the Solar System.

Scientifically, it will be led from the UK's Mullard Space Science Laboratory.

Prof Geraint Jones, who is affiliated to the University College London research centre, is the principal investigator.

The concept is a three-in-one probe: a mothership and two smaller daughter craft. They will separate near the comet to conduct different but complementary studies.

The cost for Esa is expected to be about €150m. As is customary, individual member states will provide the instrumentation and cover that tab.

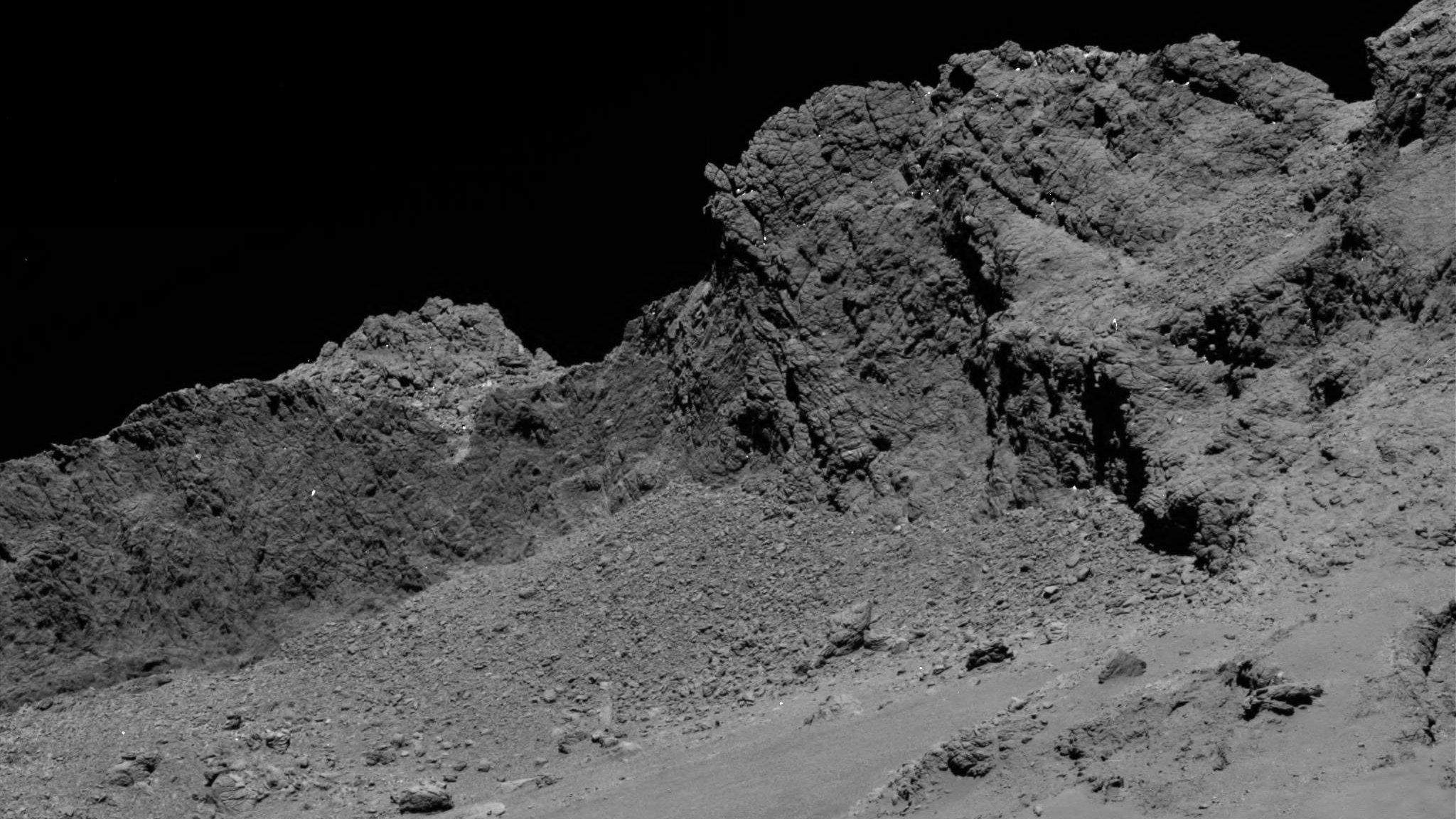

Rosetta spent two years at Comet 67P, taking thousands of photos

Interceptor was selected on Wednesday by the agency's Science Programme Committee as part of the new F-Class series - "F" standing for fast. The call for ideas only went out a year ago.

There will now be a period of feasibility assessment with industry before the committee reconvenes to formally "adopt" the concept. At that point, the mission becomes the real deal.

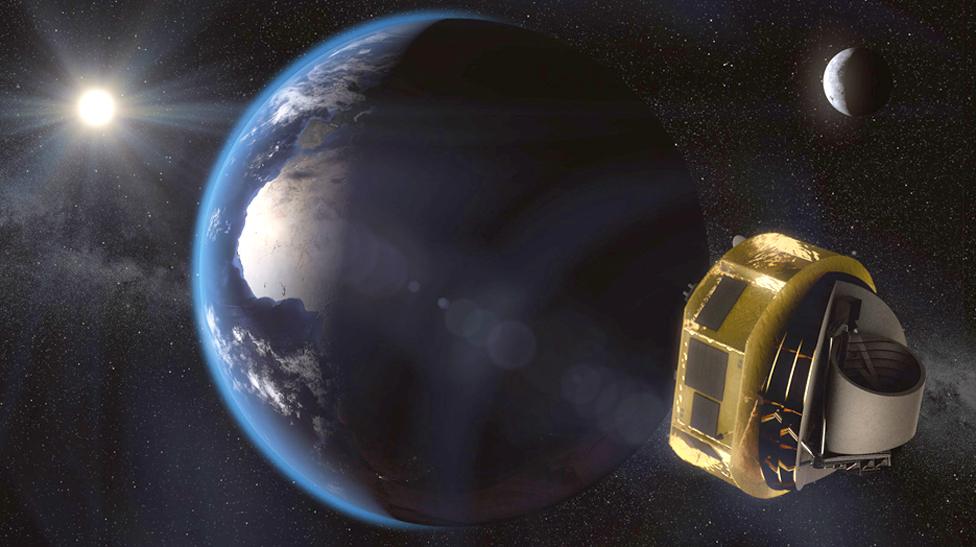

The intention is to launch the probe on the same rocket as Esa's Ariel space telescope when it goes up at the end of the next decade. This observatory won't use the full performance of its launch vehicle, and so spare mass and volume is available to do something additional.

And it's Ariel's destination that makes Interceptor a compelling prospect.

The telescope is to be positioned at a "gravitational sweetspot" about 1.5 million km from Earth. This is an ideal position from which to study distant stars and their planets - but it also represents a fast-response "parking bay" for any new mission seeking a target of opportunity.

Artwork: The Ariel space telescope will study planets around other stars

The type of comets being sought by Interceptor tend to give little notice of their impending arrival in the inner Solar System - perhaps only a few months.

That's insufficient time to plan, build and launch a spacecraft. You need to be out there already, waiting for the call.

This is what Interceptor will do. It will be sitting at the sweetspot, relying on sky surveys to find it a suitable target. When that object is identified, the probe will then set off to meet it.

The encounter will be very different from that of Rosetta at 67P. Interceptor will not orbit the comet; it will just fly past - hopefully not too quickly.

Nor will Interceptor try to repeat the landing of Rosetta's little robot, Philae.

Instead, it will be the job of those daughter craft to see if they can get in a bit closer to the comet than the mothership to acquire some more detailed information.

"The main spacecraft has the propulsion, the high-gain antenna to talk to Earth, and some instrumentation on it. That passes relatively far from the comet, about 1,000km or so upstream of the nucleus of the object. And then we deploy two cubesat-like probes that go a lot closer and do the high-risk, high-reward observations," deputy PI Dr Colin Snodgrass, from the University of Edinburgh, told BBC News.

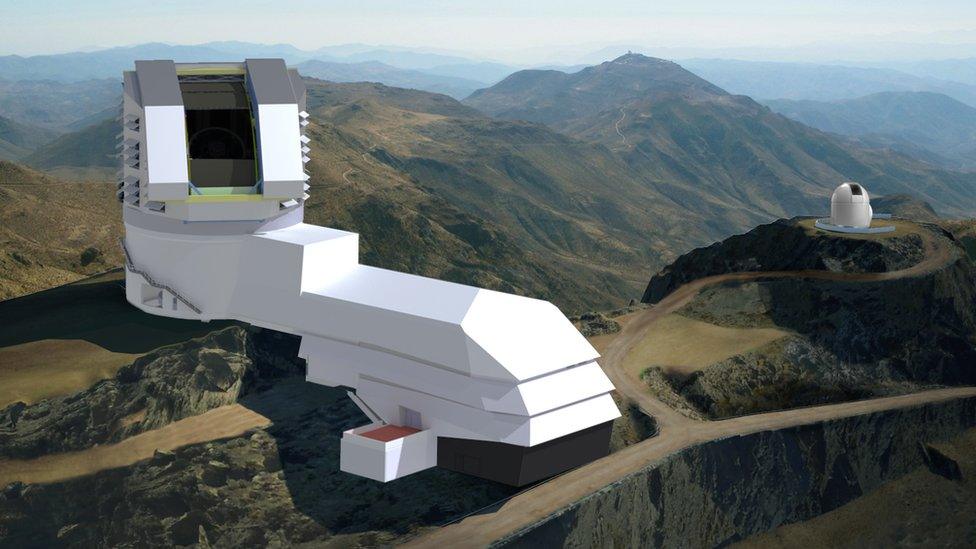

Artwork: The forthcoming LSST will look for potential targets

The comets actively encountered so far by space probes have been the repeat visitors - the ones that shuffle back and forth to make a close pass around the Sun every few years.

And because they have gone close to our star on multiple occasions, they've been chemically altered by heat, particle bombardment and even numerous impacts with other bodies.

In contrast, the comets that come in from the so-called Oort Cloud - a band of icy material that resides several hundred billion km from the Sun - will be pristine. And to see one at close quarters should give scientists completely new insights into the conditions that existed at the inception of the Solar System, and potentially from even further back in time.

The risk for Interceptor is that it could be parked up for a quite some time. The Oort Cloud comet will have to have just the right trajectory for the Esa mission. A good sample of candidates will inevitably be out of range of the probe's propulsion system.

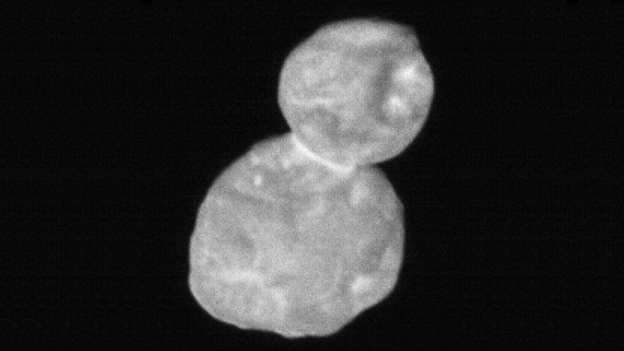

On the positive side, new Earth-based observatories, such as the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope (LSST), will soon come online. These are expected to have the sensitivity to find many more objects moving across the sky - including, possibly, more of the asteroid interlopers that occasionally pass through our Solar System from somewhere else; the bizarre cigar-shaped object 'Oumuamua being one such example.

"Yes, there's a risk we could end up sitting there with nothing really suitable," conceded Prof Mark McCaughrean, Esa's senior advisor for science and exploration. "But in the end you'd direct it at something and there are some back-up targets already identified."

These would be more of those "short period" comets. One is called 73P/Schwassmann-Wachmann, which was a possibility considered for Europe's Giotto probe in the 1980s. Giotto eventually flew past Comet Halley.

The 2028 launch is going to be quite an occasion for UK scientists. They will be leading their European partners on both the missions - Ariel and Comet Interceptor - mated atop the rocket.

Chris Lee, the head of science programmes at UK Space Agency, said: "I'm delighted that our academic community impressed Esa with a vision of what a small, fast science mission can offer.

"In 1986 the UK-led mission to Halley's Comet became the first to observe a cometary nucleus and, more recently, UK scientists took part in another iconic European comet mission, Rosetta. Now our scientists will build on that impressive legacy by attempting to visit a pristine comet for the very first time and learn more about the origins of our Solar System."

The American (Nasa) and Japanese (Jaxa) space agencies will have roles in Interceptor.

Artwork: Possible targets could even include asteroid interlopers from another solar system

- Published2 January 2019

- Published30 September 2016