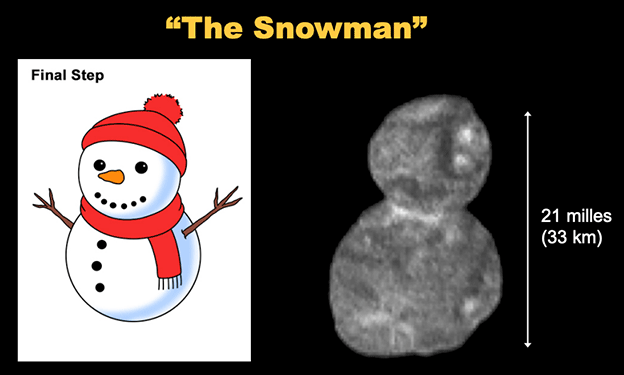

Nasa's New Horizons: 'Snowman' shape of distant Ultima Thule revealed

- Published

The "snowman" completes a full rotation every 15 hours

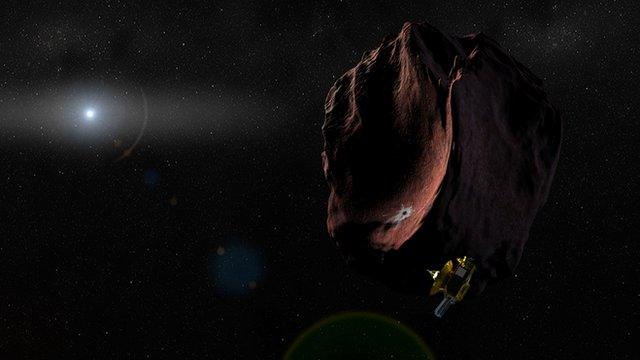

The small, icy world known as Ultima Thule has finally been revealed.

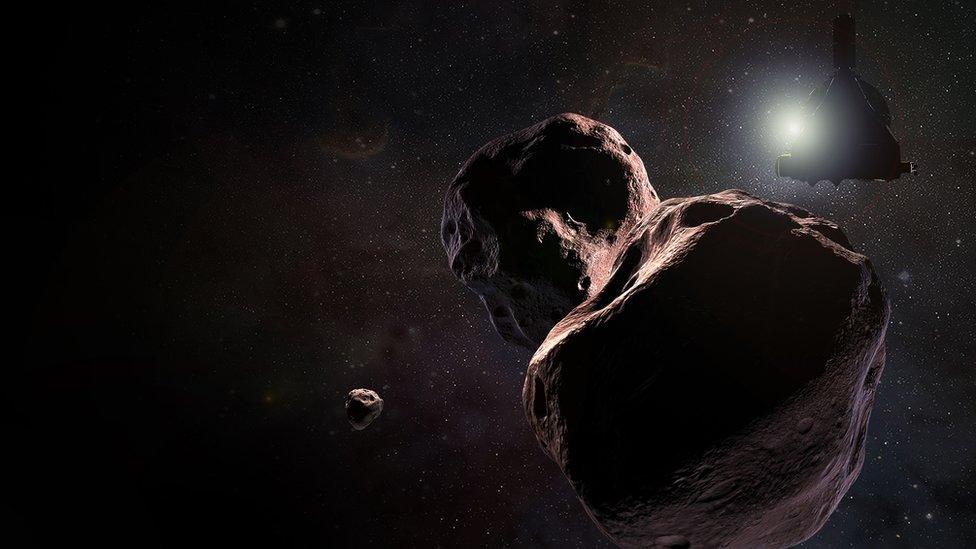

A new picture returned from Nasa's New Horizons, external spacecraft shows it to be two objects joined together - to give a look like a "snowman".

The US probe's images acquired as it approached Ultima hinted at the possibility of a double body, but the first detailed picture from Tuesday's close flyby confirms it.

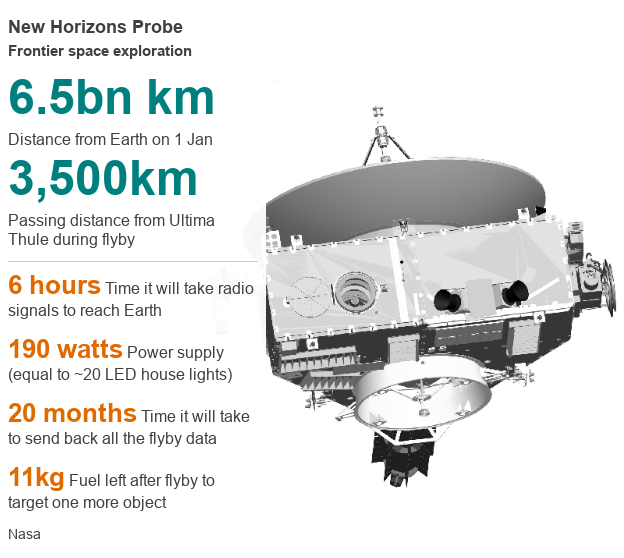

New Horizons encountered Ultima 6.5 billion km from Earth.

The event set a record for the most distant ever exploration of a Solar System object. The previous mark was also set by New Horizons when it flew past the dwarf planet Pluto in 2015.

But Ultima is 1.5 billion km further out.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

It orbits the Sun in a region of the Solar System known as the Kuiper belt - a collection of debris and dwarf planets.

There are hundreds of thousands of Kuiper members like Ultima, and their frigid state almost certainly holds clues to how all planetary bodies came into being some 4.6 billion years ago.

The mission team thinks the two spheres that make up this particular object probably joined right at the beginning, or very shortly after.

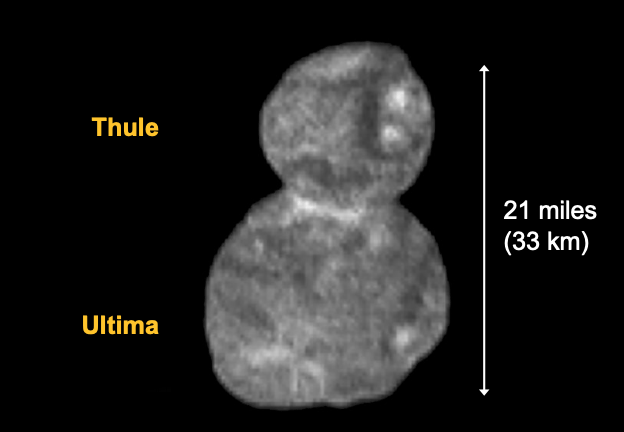

The scientists have decided to call the larger lobe "Ultima", and the smaller lobe "Thule". The volume ratio is three to one.

Jeff Moore, a New Horizons co-investigator from Nasa's Ames Research Center, said the pair would have come together at very low speed, at maybe 2-3km/h. He joked: "If you had a collision with another car at those speeds you may not even bother to fill out the insurance forms."

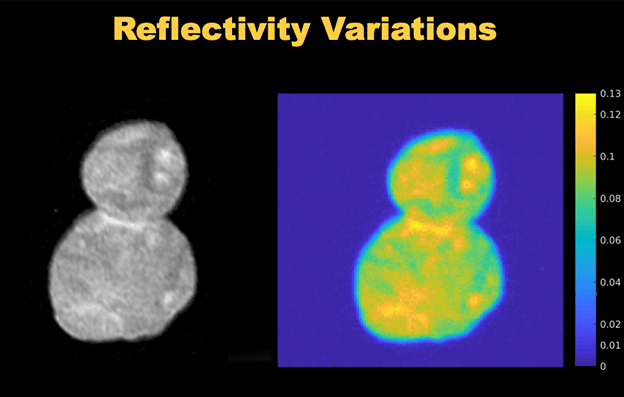

Overall, Ultima Thule is dark, but there is quite a bit of brightness variation

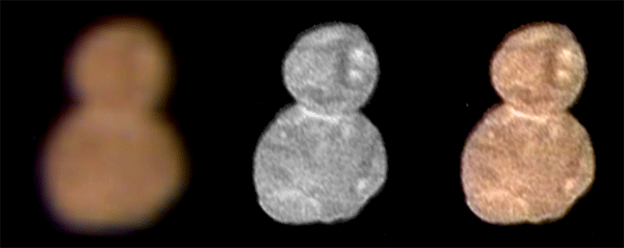

One of the probe's instruments recorded the colour (L) of Ultima Thule. This has been laid over the high-resolution B&W image (C) to produce a combination (R)

The new data from Nasa's spacecraft also shows just how dark the object is. Its brightest areas reflect just 13% of the light falling on them; the darkest, just 6%. That's similar to potting soil, said Cathy Olkin, the mission's deputy project scientist from the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI).

It has a tinge of colour, however. "We had a rough colour from Hubble but now we can definitely say that Ultima Thule is red," added colleague Carly Howett, also from SwRI.

"Our current theory as to why Ultima Thule is red is the irradiation of exotic ices." Essentially, its surface has been "burnt" over the eons by the high-energy cosmic rays and X-rays that flood space.

The New Horizons team is celebrating an extraordinary achievement

Principal Investigator Alan Stern paid tribute to the skill of his team in acquiring the image as New Horizons flew past the object, reaching 3,500km from its surface at closest approach.

The probe had to target Ultima very precisely to be sure of getting it centre-frame in the view of the cameras and other instruments onboard.

"[Ultima's] only really the size of something like Washington DC, and it's about as reflective as garden variety dirt, and it's illuminated by a Sun that's 1,900 times fainter than it is outside on a sunny day here on the Earth. We were basically chasing it down in the dark at 32,000mph (51,000km/h) and all that had to happen just right," the SwRI scientist said.

You might also like:

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Less than 1% of all the data gathered by New Horizons during the flyby has been downlinked to Earth. The slow data-rates from the Kuiper belt mean it will be fully 20 months before all the information is pulled off the spacecraft.

The best of the pictures shared by the team on Wednesday were taken while the probe was still 28,000km from Ultima and discern surface features larger than 140m across. Pictures are expected in February that were captured at the moment of closest approach and these will have a resolution of about 35m per pixel.

What's so special about the Kuiper belt?

Several factors make Ultima Thule, and the domain in which it moves, so interesting to scientists.

One is that the Sun is so dim in this region that temperatures are down near 30-40 degrees above absolute zero - the lower end of the temperature scale and the coldest atoms and molecules can possibly get. As a result, chemical reactions have essentially stalled. This means Ultima is in such a deep freeze that it is probably perfectly preserved in the state in which it formed.

Another factor is that Ultima is small (about 33km in the longest dimension), and this means it doesn't have the type of "geological engine" that in larger objects will rework their composition.

And a third factor is just the nature of the environment. It's very sedate in the Kuiper belt.

Unlike in the inner Solar System, there are probably very few collisions between objects. The Kuiper belt hasn't been stirred up.

Prof Stern said: "Everything that we're going to learn about Ultima - from its composition to its geology, to how it was originally assembled, whether it has satellites and an atmosphere, and that kind of thing - is going to teach us about the original formation conditions in the Solar System that all the other objects we've gone out and orbited, flown by and landed on can't tell us because they're either large and evolve, or they are warm. Ultima is unique."

What does New Horizons do next?

First, the scientists must work on the Ultima data, but they will also ask Nasa to fund a further extension to the mission.

The hope is that the course of the spacecraft can be altered slightly to visit at least one more Kuiper belt object sometime in the next decade.

New Horizons should have just enough fuel reserves to be able to do this. Critically, it should also have sufficient electrical reserves to keep operating its instruments into the 2030s.

The longevity of New Horizon's plutonium battery may even allow it to record its exit from the Solar System.

The two 1970s Voyager missions have both now left the heliosphere - the bubble of gas blown off our Sun (one definition of the Solar System's domain). Voyager 2 only recently did it, in November.

And in case you were wondering, New Horizons will never match the Voyagers in terms of distance travelled from Earth. Although New Horizons was the fastest spacecraft ever launched in 2006, it continues to lose ground to the older missions. The reason: the Voyagers got a gravitational speed boost when they passed the outer planets. Voyager-1 is now moving at almost 17km/s; New Horizons is moving at 14km/s.

The BBC's Sky At Night programme will broadcast a special episode on the flyby on Sunday 13 January on BBC Four at 22:30 GMT. Presenter Chris Lintott, external will review the event and discuss some of the new science to emerge from the encounter with the New Horizons team.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published1 January 2019

- Published1 January 2019

- Published18 December 2018

- Published9 May 2018

- Published12 December 2017

- Published30 August 2015

- Published10 July 2015