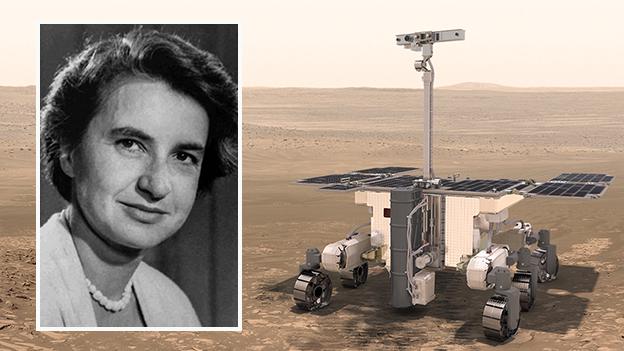

Rosalind Franklin Mars rover nears completion

- Published

This week has seen the close-out of the rover's body with the solar panel deck

The "Rosalind Franklin" Mars rover is in its final stages of construction.

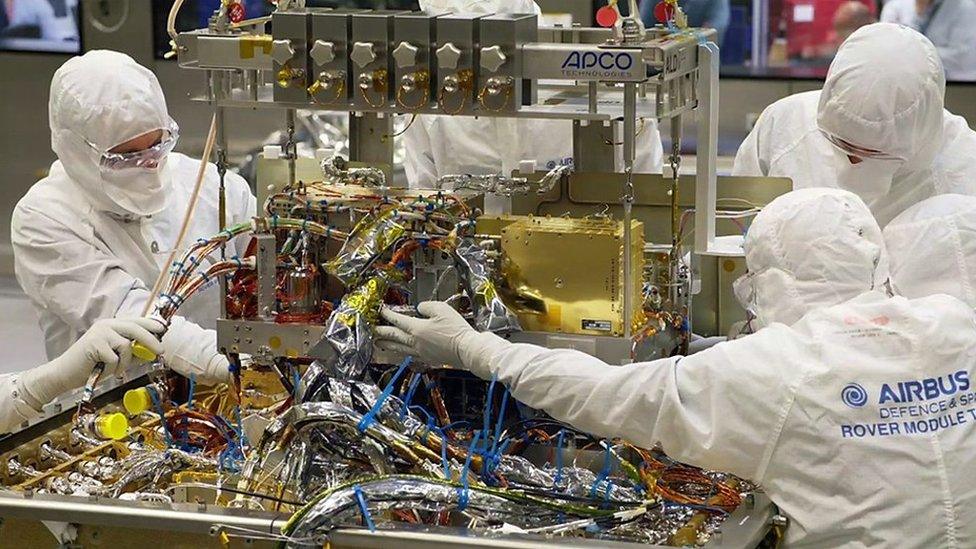

Engineers at Airbus (UK) are running through the end tasks of assembly and expect to get the six-wheeled vehicle out the door before August is up.

Among the last items being attached are the robot's solar panels, and its mast and camera system.

Rosalind Franklin, external is booked to launch from Earth in July next year. When she lands, in 2021, the joint European-Russian mission will search for life.

Most likely, this will be evidence of past biology, but it's not inconceivable there are also microbes present on the Red Planet today.

If there are, these organisms are almost certainly to be found underground, away from Mars' harsh surface environment, and the rover will be equipped with a drill, external to seek them out.

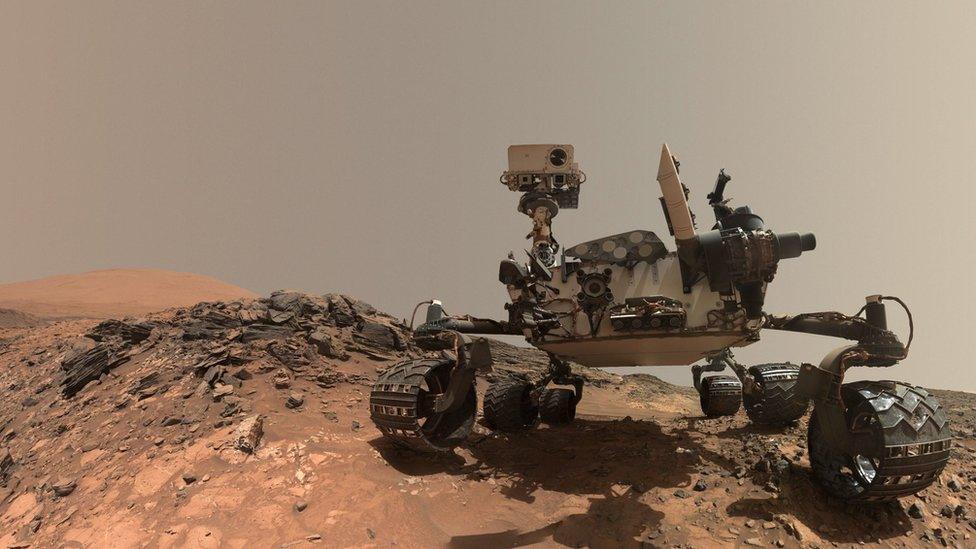

Artwork of the finished rover: The mast gives the camera a 2m-high vantage point

All of the instruments Rosalind Franklin needs for this endeavour are now installed.

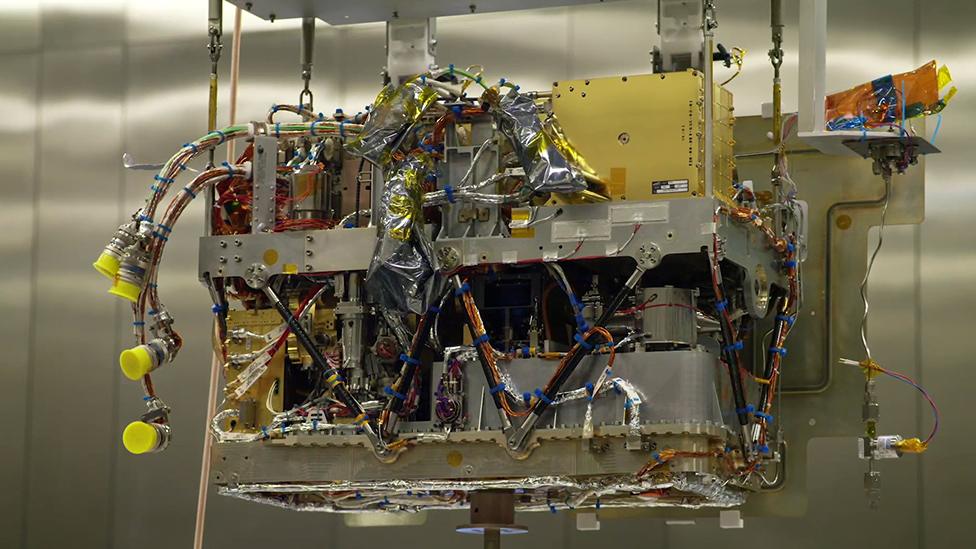

Her three primary scientific tools, external - the Moma chemistry lab, external, the Raman laser spectrometer, external and the MicroOmega hyperspectral microscope, external - are all housed within her belly inside a structure that looks a bit like a bathtub.

This volume also accommodates the service module, which includes items such as the computers that will control the rover.

The bathtub was closed this week with the addition of a lid of solar cells from the Leonardo (Italy) company.

In the coming days, the integration will take place of a long pole from Ruag (Austria). Attached atop this mast will be an imaging system, known as PanCam, external. This is led from University College London. PanCam will take the pictures that identify the places of interest on Rosalind Franklin's drive across the Red Planet's surface.

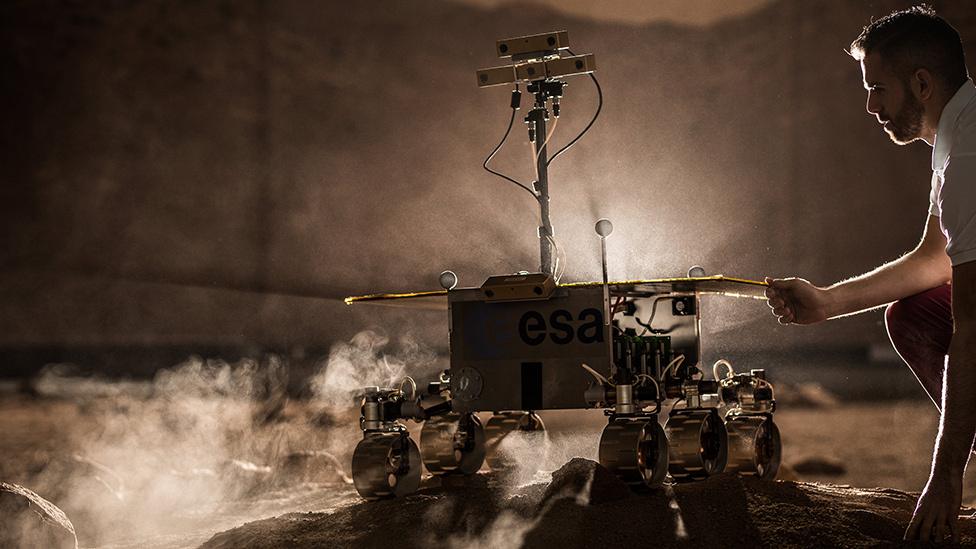

The PanCam is the one UK-led instrument on the Rosalind Franklin rover

With these final large items in place, it's then a case of hooking up the connecting cables.

The concluding job is the installation of the actuator drive electronics (ADE), which sit just under the lip of the deck of solar cells.

It's through the ADE units that the commands will run to the mechanisms that turn and point the wheels, open the solar panels, lift the mast and swivel the camera head.

The second of two required ADEs has only just arrived from Thales Alenia Space (Spain).

Mars probes are not normally built using the "just in time delivery" techniques of the automotive industry - but the critical nature of these particular components means their fabrication and testing schedule has gone right to the wire.

"Rosalind Franklin is looking like the real rover now," Chris Draper, the flight model operations manager at Airbus UK, told BBC News.

"We started assembly in December, and we thought we might deliver the rover in late July. So, Ok - it's now August, but we've performed well, I think. You have to remember no-one has ever done this in Europe before - building a Mars rover in a biologically controlled area."

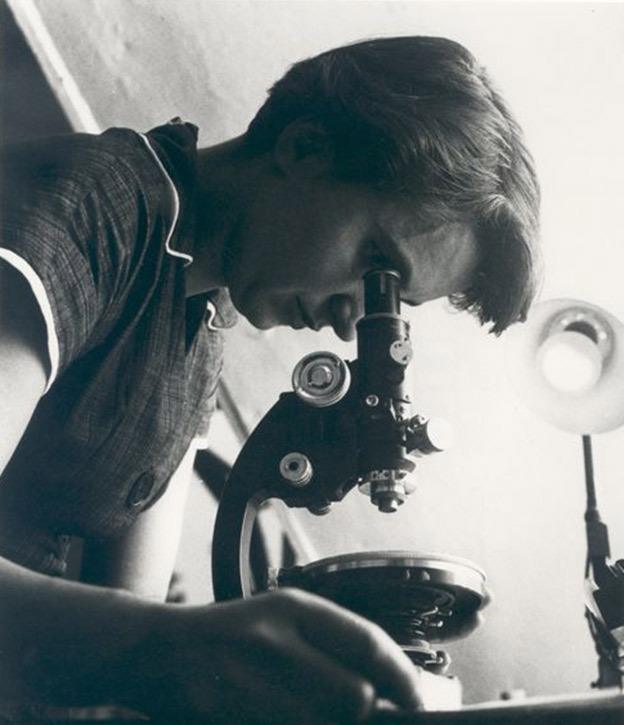

The rover is named after the British scientist who helped decipher the structure of DNA

That's a reference to the spotlessly clean conditions under which Rosalind Franklin has been put together.

Because her goal is to identify traces of life, scientists need certainty that anything that's detected on Mars is from Mars - not from the Airbus facility in Stevenage in England, or from any of the other cities around Europe and Russia where rover components have been manufactured.

There are strict rules governing what's termed "planetary protection", overseen by the international Committee on Space Research (Cospar). It has a scale of permitted contamination running through one to five - five being the most onerous and the level that would guide a mission bringing samples from Mars back to Earth.

Rosalind Franklin is a category 4b mission.

This allows it to land on the Red Planet and drill for biology. Its drill head and associated ultra-clean areas must have no more than 0.03 bacterial spores per square metre. A spore is the reduced, resilient form assumed by a dormant bacterium - a condition that could feasibly enable it to survive the journey through space to Mars.

The vehicle as a whole has a set limit of 9,800 spores.

"This is a big challenge," said Silvio Sinibaldi, the planetary protection officer at Airbus.

"It's why we work in a bioclean facility and we dress the way we do, in 'bunny suits', with double gloves, masks and glasses. But it's not a magic wand, and it requires all the people to have total awareness and constant training.

"To give you an example - 9,800 spores can be found on a normal pinhead, and in the Airbus cleanroom we have 150 square metres of accountable surfaces."

Cleanliness is paramount in the assembly process

Cleanliness is maintained from the component level upwards.

Every part that has arrived in Stevenage has gone through some form of decontamination that might have involved extended baking (110C minimum) in an oven, exposure to gamma radiation or an electrified gas (plasma), and perhaps even the application of hydrogen peroxide.

Surfaces are regularly swabbed to review their contamination risk.

The obsessiveness will be maintained when Rosalind Franklin is taken from Stevenage to Airbus (France) in Toulouse for a big round of testing.

She'll depart in a bag, inside a box inside another box.

This containment won't be opened until she's safely within the super-clean testing yurt, or tent, that's been constructed for her in the French city.

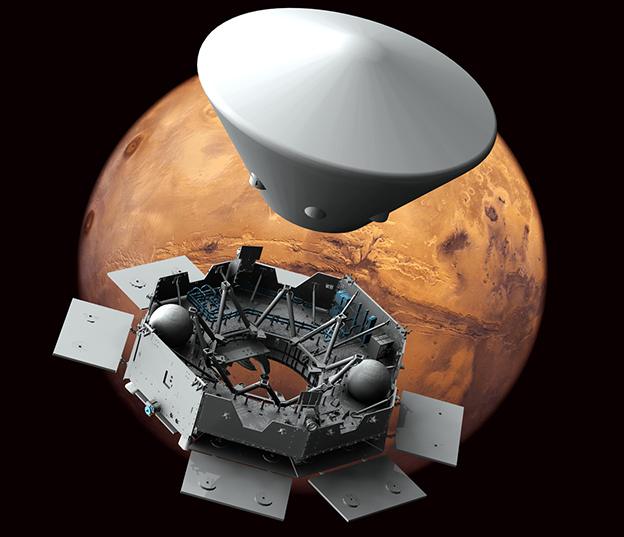

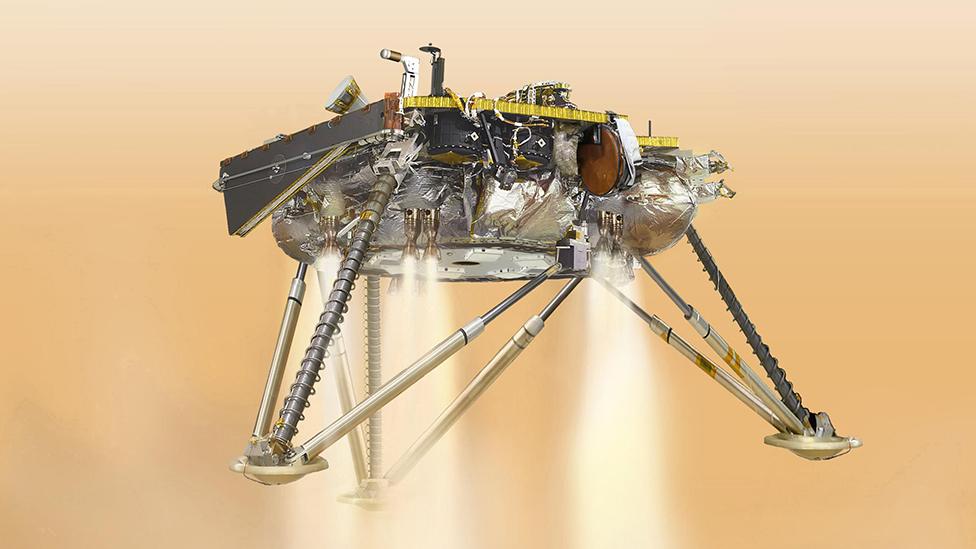

Kazachok lander: The rover needs a means to get it safely to the surface of Mars

We're now less than one year to the opening of the launch window for the rover on 25 July, 2020.

In the intervening months, Rosalind Franklin must be joined to all the equipment needed to get her to the Red Planet and put her safely on the surface.

These hardware items are the shepherding spacecraft that will carry the robot on the eight-month cruise to Mars, and the Russian landing mechanism, dubbed Kazachok, external, that will control the rover's descent through the atmosphere to the ancient plain that's been chosen as the landing location.

Coming respectively from OHB System (Germany) and NPO Lavochkin (Russia), these contributions will be joined to Rosalind Franklin at a factory in Cannes, France, before eventual shipment to the launch site at Baikonur, Kazakhstan, early next year.

Artwork: The rover will travel to Mars inside a capsule attached to a German cruise vehicle

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published24 June 2019

- Published17 May 2019

- Published30 May 2019

- Published10 May 2019

- Published14 March 2019

- Published13 February 2019

- Published7 February 2019