Fracking: UK shale reserves may be smaller than previously estimated

- Published

Cuardrilla have recently resumed fracking for shale gas in Lancashire

Previous projections of the potential amount of shale gas under the UK may have been significantly overestimated, according to a new study.

Instead of 50 years of gas at the current rate of consumption, this new research, external suggests there are just 5-7 years' supply.

But the UK's fracking industry, which represents companies like Cuadrilla, dismissed the report.

The said the sample size was too small to draw serious conclusions.

The recovery of shale gas through hydraulic fracturing or fracking has been a slow moving and controversial affair in the UK over the past decade.

Attempts by oil and gas companies to drill wells and extract gas have been held up by planning issues, concerns about earth tremors and public displays of disaffection over the issue.

Through it all, the government and industry have maintained faith in the process.

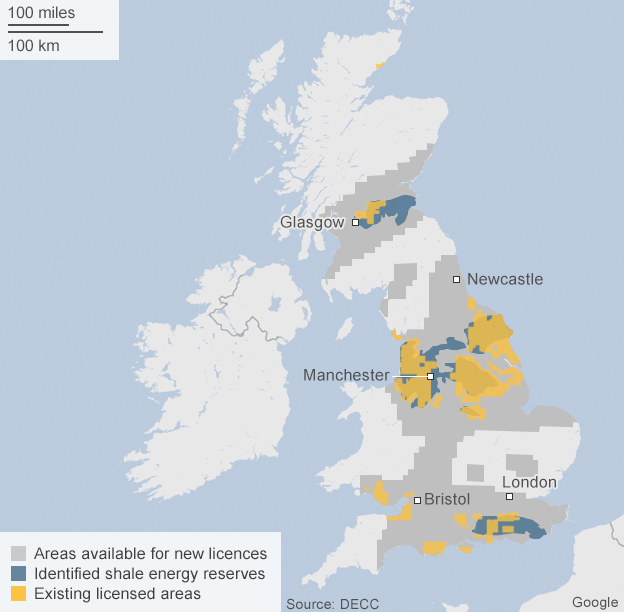

They argued that there was huge potential for fracked gas particularly in the Bowland shale, a geological formation that runs under Lancashire, Yorkshire, parts of the Midlands and into North Wales.

Plans for test drilling have drawn public protests in a number of locations around the UK

The optimistic view was based in part on a study published in 2013 by the British Geological Survey (BGS) which issued a very positive report, external on the likely amount of gas in place under the Bowland.

That study suggested that it was one of the world's biggest reserves, containing some 1,300 trillion cubic feet of shale gas.

"To put that in context," wrote former Prime Minister David Cameron at the time, "even if we extract just a tenth of that figure, that is still the equivalent of 51 years' gas supply."

But there were concerns expressed at the time that the estimate was on the high side.

New approach

Now, scientists at the University of Nottingham and the BGS have developed a new method for analysing the gas content of shale, which they believe gives them a more accurate estimate of the overall potential.

"In terms of the total gas in place, the mean value from the 2013 study was 1,300 trillion feet of gas, we are struggling to get anywhere above 200 trillion feet," said Prof Colin Snape from the University of Nottingham, the lead author on the paper.

"The data we've got from the two shales we've looked at are very consistent - and gas companies Cuadrilla and Third Energy have just published two papers in the last year where they have taken core samples and measured the gas that's evolved and that data is very, very consistent with our own data."

According to the new study, the amount of gas in place, assuming an economic recovery rate of 10% would be a maximum of 20 trillion cubic feet, which would equate to around seven years' worth of gas at current UK rates of consumption.

Other researchers were impressed with the new method developed by the researchers at Nottingham.

"The results bring bad news to those hoping that northern England is floating on a bed of cheap and abundant gas," said Prof Stuart Haszeldine, Professor of Geology and Carbon Storage, University of Edinburgh, who was not involved with the study.

"Abundant hydrocarbons may have been generated in the past, but have leaked away to the Earth's surface many millions of years ago. Not only have all those hydrocarbon horses bolted, but there is no longer a secure stable door to retain very large quantities of present-day gas in these shales."

However, some of the leading experts at the BGS were cautious in their interpretation of the study, even though several of their own scientists were involved in the paper.

"Early indications published today suggest that it is possible there is less shale gas resource present than previously thought," said Prof Mike Stephenson, chief scientist for decarbonisation and resource management, at the BGS.

"However the study considered only a very small number of rock samples from only two locations."

"BGS has continued to study resource estimation in shales over the past 16 years and further studies are still required to further refine estimates of shale gas resources."

Cuadrilla, the company which has recently resumed fracking a shale gas well in Lancashire, was blunt in its rejection of the new paper.

Protestors have tried to shut down Cuadrilla's fracking operations in Lancashire

"Those involved in publishing this should be embarrassed," said Francis Egan, Cuadrilla chief executive.

"We hold more data and technical experience of the Bowland shale than anyone else in the UK yet not once did anyone from this research group or Nottingham University contact us for our view or input."

UKOOG, the body which represents the UK's onshore oil and gas industry, also rejected the implications of the study.

"To date we have made significant advancements in the understanding of the resource potential contained within UK shale, with very encouraging results seen at both Springs Road and Preston New Road which have demonstrated properties in line with world class, US shale plays," said Ken Cronin, chief executive of UK Onshore Oil and Gas.

"What we know now is that we have a world class resource which has broadly supported the estimates originally published by the British Geological Survey. Indeed, in terms of potential gas flow indications, the results are at the upper end of our original forecasts."

"The only way to provide accurate estimates of how much gas is likely to be produced is to drill, hydraulically fracture and test many wells," said Prof Quentin Fisher, from the University of Leeds, who was not involved with the study.

"Which is exactly the intention of companies holding shale gas licences in the UK."

The study has been published, external in the journal Nature Communications.