Etna volcano: The Mountain Man celebrates his life's work

- Published

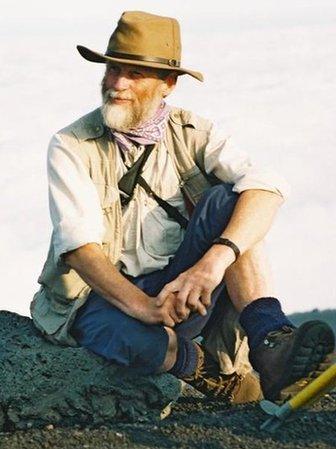

1990s: John also maps the position and volume of lava fields

Is it love; is it an obsession? It's a bit of both concedes John Murray, who this year celebrates 50 years on Mount Etna.

The British professor heads to Sicily every summer to measure the changing curves of its famous volcano.

"I just never tire of seeing it; the eruptions are spectacular," he says.

Family, friends and former assistants will gather this weekend to celebrate his life's work at a party in Nicolosi, the "gateway" town to the mountain.

"We'll show some slides and share some memories," he told BBC News.

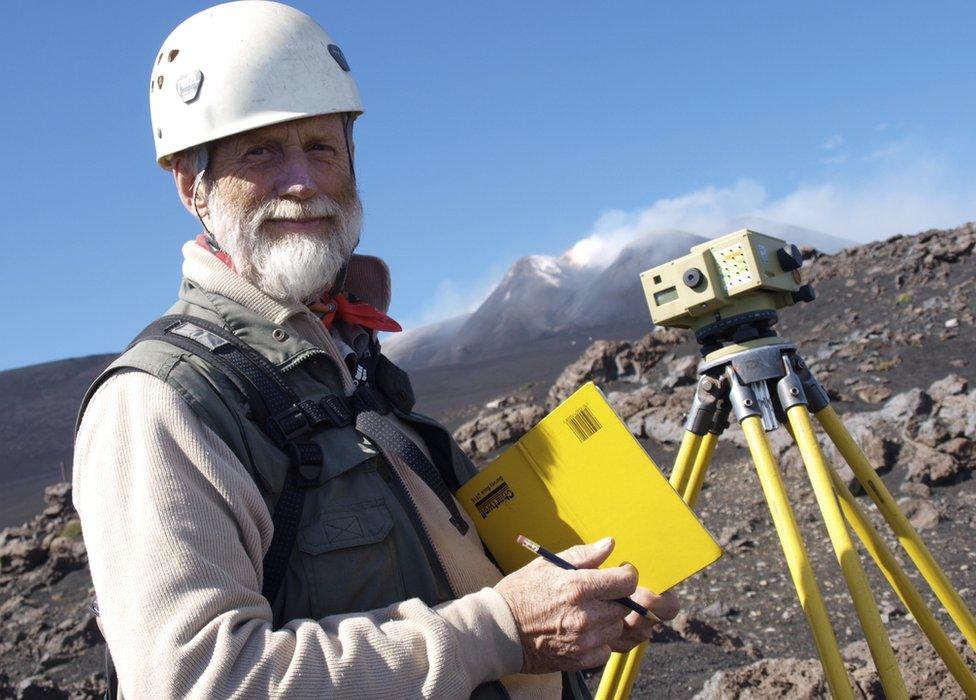

John Murray today: "For heaven's sake, it's not as if this is a job"

John will also relate his latest findings which are published in yet another Etna paper, external.

The new one is a bit different, however, because, in a sense, the results summarise everything he's been doing on the volcano this past half-century.

But to understand what he's learnt, you need to know a little of the way the Open University scientist works.

He's a surveyor at heart and since 1975, he's painstakingly done the exact same thing every year - measuring heights at different points across the summit.

It's by tracking the changing shape of Etna that you get some insight into the "engine" that drives its eruptive behaviour.

John made his first visit to Etna in 1969 - and fell in love with the mountain

Today, you might think this is a job for specialist GPS instruments; and it's true, satellites are now an essential part of a volcanologist's toolkit. But John also still keeps faith with the traditional technique of levelling.

2000s: John persists with the techniques he's always used

You'll have seen this method practised on many a construction site.

One person holds a staff while another some distance away looks at the vertical ruler through a small telescope. Moving in tandem through a sequence of points, the team builds up a series of height marks relative to a known baseline, or datum. Done properly, it gives millimetric precision.

Every summer, John and his assistants will perform the levelling from 3,100m, up near the top of Etna, down to 1,300m.

"I don't know anyone else who does this now; and I used to think maybe it wasn't worth it. But in the last few years, it's been most satisfying because the pieces in the jigsaw have started to fall into place," he said.

So what's he seen? John's latest paper will detail how a section of the summit of Etna has subsided nearly 4m over the 43 years he's been levelling.

The area of subsidence runs in a north-south trough (what geologists call a graben), curving east at its northern end. Over the same period, the land either side of the subsiding trough - the walls of the graben, if you like - has moved apart more than 8m.

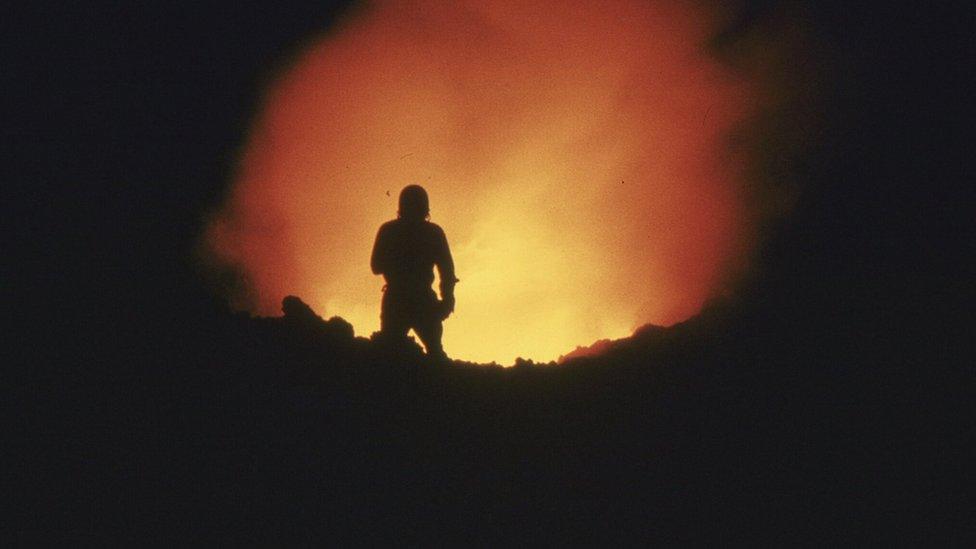

1970s: The frequent eruptions are spectacular

John says only the levelling technique could have found this feature. Ashfall and frequent lava flows make it very hard for radar satellites, for example, to anchor their vision on a ground target and make consistent measurements.

"This feature has almost certainly been caused by a combination of the sliding of Etna downslope towards the sea (at a rate of 14mm/yr), and outward radial gravitational spreading of the edifice," explains John.

"For me, the most interesting thing is that it suggests a self-perpetuating eruptive mechanism that has continued for hundreds, and probably thousands of years in the past, and will continue into the foreseeable future."

John is looking forward to seeing again many of his past assistants at the Nicolosi party. They were all his students, and he's intensely proud that so many went on to forge successful careers in the Earth sciences.

As for his future, he intends to keep coming back to Etna year after year, for "the next 300 years at least", he jokes. "I'll keep doing it for as long as I can. For heaven's sake, it's not as if this is a job."

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk or follow Jon on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external