Microplastics: Seeking the 'plastic score' of the food on our plates

- Published

Plastic from Almaciga Beach, on the north coast of the Canary Island of Tenerife

Microplastics are found everywhere on Earth, yet we know surprisingly little about what risks they pose to living things. Scientists are now racing to investigate some of the big unanswered questions.

Daniella Hodgson is digging a hole in the sand on a windswept beach as seabirds wheel overhead. "Found one," she cries, flinging down her spade.

She opens her hand to reveal a wriggling lugworm. Plucked from its underground burrow, this humble creature is not unlike the proverbial canary in a coal mine.

A sentinel for plastic, the worm will ingest any particles of plastic it comes across while swallowing sand, which can then pass up the food chain to birds and fish.

"We want to see how much plastic the island is potentially getting on its shores - so what is in the sediments there - and what the animals are eating," says Ms Hodgson, a postgraduate researcher at Royal Holloway, University of London.

"If you're exposed to more plastics are you going to be eating more plastics? What types of plastics, what shapes, colours, sizes? And then we can use that kind of information to inform experiments to look at the impacts of ingesting those plastics on different animals."

Lugworm living in the sand in Great Cumbrae, Scotland

The beach at the town of Millport

Microplastics are generally referred to as plastic smaller than 5mm, or about the size of a sesame seed. There are many unanswered questions about the impact of these tiny bits of plastic, which come from larger plastic debris, cosmetics and clothes. What's not in dispute is just how far microplastics have travelled around the planet in a matter of decades.

"They're absolutely everywhere," says Hodgson, who is investigating how plastic is making its way into marine ecosystems. "Microplastics can be found in the sea, in freshwater environments in rivers and lakes, in the atmosphere, in food."

Multi-million-dollar question

The island of Great Cumbrae off Scotland's Ayrshire coast is a favourite haunt of day trippers from nearby cities like Glasgow. A ferry ride away from the town of Largs, it's a retreat for cyclists and walkers, as well as scientists working at the Millport Field Studies Council, external research station on the island. On a boat trip off the bay to see how plastic samples are collected from the waves, a dolphin joins us for a while and swims alongside.

Plastic collected on Great Cumbrae

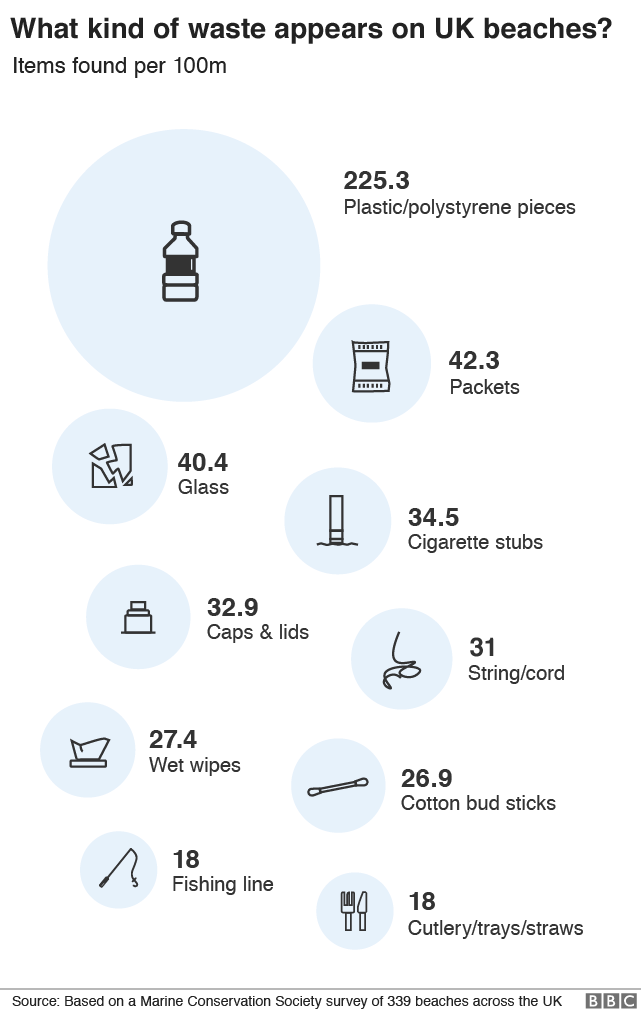

Even in this remote spot, plastic pollution is visible on the beach. Prof David Morritt who leads the Royal Holloway University research team points out blue twine and bits of plastic bottles that wash up with the seaweed at Kames Bay. Where it's coming from is the "multi-million-dollar question", he says, holding up a piece of blue string.

"We've just been looking at some of the plastic washed up on the strand line here and you can tell fairly obviously it's fishing twine, or it's come from fishing nets. Sometimes it's much more difficult. By identifying the type of polymer, the type of plastic it is and then by matching that with the known uses of those polymers you can sometimes make an educated guess of where that plastic's likely to have come from."

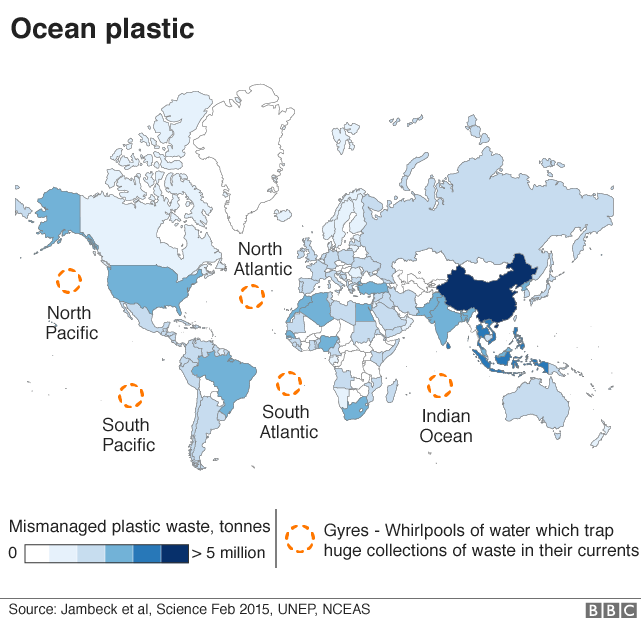

From the Great Pacific garbage patch to riverbeds and streams in the UK, microplastics are among the most widespread contaminants on the planet, turning up from the deepest parts of our oceans to the stomachs of whales and seabirds. The explosion in plastic use in recent decades is so great that microplastics are becoming a permanent part of the Earth's sedimentary rocks.

While studying rock sediments off the Californian coast, Dr Jennifer Brandon discovered disturbing evidence of how our love of plastic is leaving an indelible mark on the planet.

"I found this exponential increase in microplastics being left behind in our sediment record, and that exponential increase in microplastics almost perfectly mirrors the exponential increase in plastic production," she says. "The plastic we're using is getting out into the ocean and we're leaving it behind in our fossil record."

Age of plastic

The discovery suggests that after the bronze age and the iron age, we're now entering the age of plastic.

"In decades from now, hundreds of years from now, plastic will be used most likely as the geological marker of what we've left behind," says Dr Brandon of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, UC San Diego. "We're basically littering the ocean with chemical-laced oil. That's not a recipe for a very healthy ocean."

One big unknown is how microplastics might affect living beings. In August, the World Health Organization (WHO) released a report, external concluding that while particles in tap and bottled water do not pose an apparent health hazard, more research and evidence is needed.

Dr Brandon says we need to know the "plastic score" of the animals that are ending up on our dinner plates.

"These microplastics are small enough to be eaten by plankton and by coral polyps and by filter-feeding mussels, but how are they bio-accumulating up the food chain?" she says. "By the time you get to a huge fish, is that fish eating plastic itself or is it eating thousands of little fish that are eating thousands of plankton, that are eating thousands of microplastics.

"How high is the plastic signature in something like a tuna by the time it gets on your dinner plate? And that isn't always known."

Scratching the surface

A few weeks after the Scotland field trip, I visit the lab at Royal Holloway to see what's being found in the samples collected on the island. Water samples and sediments have been filtered to remove the plastic, which is examined under the microscope, together with plastic found in marine animals. Hodgson says plastic has been found in all the samples, including the animals, but especially in Kames Bay on the southern coast of the island.

Daniella Hodgson in the lab at Royal Holloway, University of London.

Animals such as whales, dolphins and turtles are eating large plastic debris such as plastic bags, that can cause starvation, she says. But lots of little bits of data are showing more subtle effects from eating microplastics.

"It may not be harming them such as killing them, but over time there might be cellular damage, it might be affecting their energy balance and how they can deal with that, so over long periods of time it might be causing nasty effects down the line," says Daniella Hodgson, who is collaborating with researchers, external at the Natural History Museum, London.

The answers to some of these questions will become clear with further research. Others will take a long time to answer.

"We know that there's a lot of microplastic and we keep finding it everywhere we look for it," says Dr Brandon. "But the implications of the health effects of it and how it really affects animals and humans, we're only just starting to scratch the surface of those questions."

Follow Helen on Twitter, external.