'Molar Berg' does a quick Antarctic pirouette

- Published

Molar Berg is the biggest ice block to come off Amery in more than 50 years

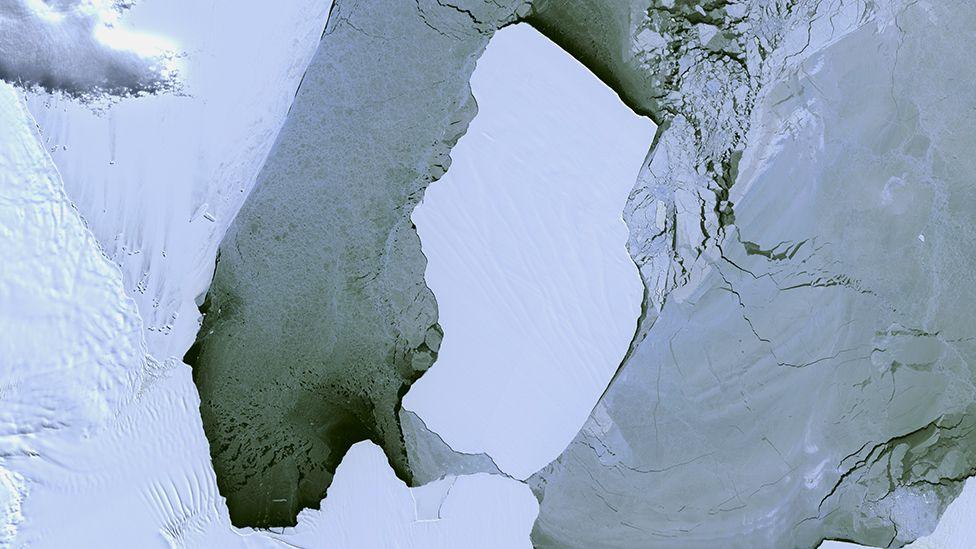

The EU's Sentinel-2 satellite system got a great view of Antarctica's newest giant iceberg on Wednesday.

Cloudless skies over the east of the continent meant the 315-billion-tonne block could be seen in all its glory.

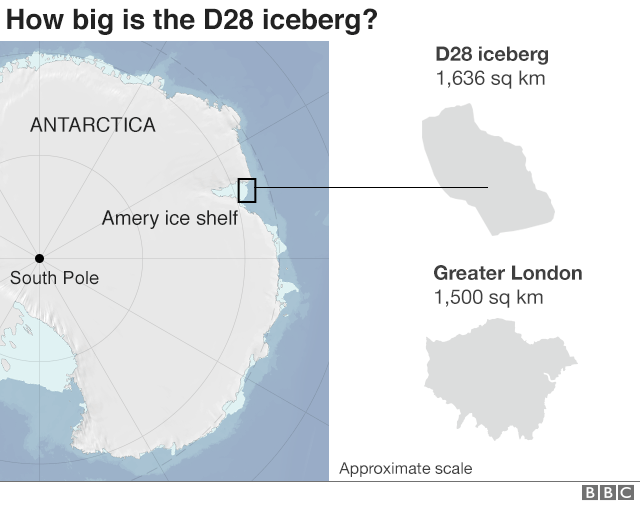

The 1,636 sq km frozen chunk broke off the Amery Ice Shelf two weeks ago and has already spun around by 90 degrees.

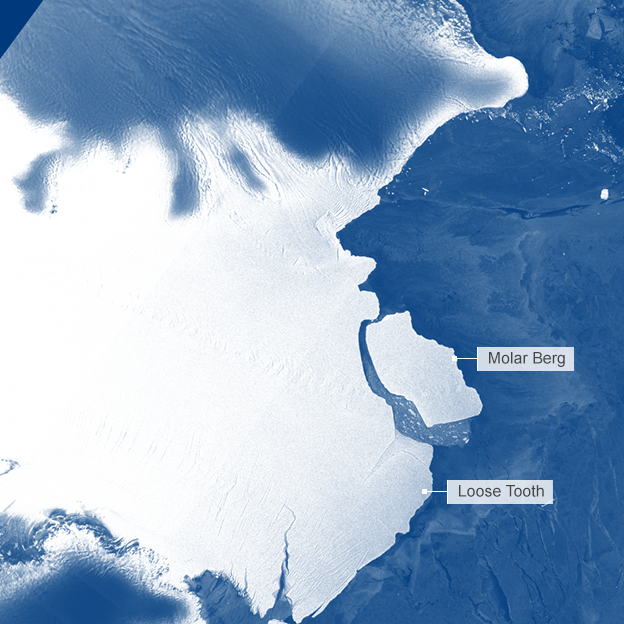

The block has been nicknamed "Molar Berg" by scientists because it calved from next to a segment of ice that looks from space like a "Loose Tooth".

This moniker is, however, unofficial. The US National Ice Center runs the recognised nomenclature for icebergs and it has given the hulking mass the designation D28.

Antarctica's nearshore winds and currents tend to push the big bergs in a westerly direction. Often they will play "bumper cars", bashing the coastline and knocking other lumps out of the ice shelf and themselves.

And by the looks of it, Molar Berg is heading straight for a head-on collision with another part of Amery.

With Antarctica's long "polar night" coming to an end and the Sun getting ever higher in the sky, the Sentinel-2 system is once again tracking changes across the continent. As an optical sensor, the two-spacecraft system can only see lit portions of the Earth's surface.

In the dark days of winter, radar satellites like the Sentinel-1 system are the only way to keep abreast of developments.

The Sentinel-2 image at the top of the page was processed by remote sensing specialist Iban Ameztoy.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Stef Lhermitte at the Technical University of Delft, Netherlands, also has a nice "then" and "now" sequence, which shows how far Molar Berg has moved.

D28/Molar Berg is the biggest slice of ice in more than 50 years to come off Amery.

The ice shelf, the third largest in Antarctica, is a key drainage channel for the east of the continent.

It is essentially the floating extension of a number of glaciers that flow off the land into the sea.

Losing bergs to the ocean is how these ice streams maintain equilibrium, balancing the input of snow upstream. So, the calving of Molar Berg is regarded as an entirely natural event. There is no data to show climate change has altered the dynamics in this particular region.

The only surprise for scientists is that it wasn't Loose Tooth that "extracted" itself. This section of ice at the edge of Amery has been wobbling for more than a decade. Researchers thought it would have come away by now, but still it refuses to calve.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Radar systems like Sentinel-1 can see the surface no matter the conditions

Follow Jonathan on Twitter., external